When I teach Design history courses, my students love how similar events, people and milestones are neatly packaged into movements and eras with interesting names, usually with an “ism” thrown in for good measure. One of our favorite thinking exercises is to try and apply a movement or era name to the art happening today. We mostly think of Frankenstein-like names, following the contemporary trend of making combinations of specific cultural groups, places, with older movement names. Like Jewish and futurism, we learned that every movement has its ancestors, both good and bad, even if they didn’t call themselves by the same name. I can say that as teacher and artist in this story, the feeling of placing oneself into the continuum of creative history is inspirational and revealing of purpose.

Before “Jewish futurism” was a modern phrase, there were lowercase “f” futurists in Biblical prophets, medieval mystics, modern artists, inventors, and one rejected capital “F”, Futurist (Italian), who for better for for worse, all had dreams with variegated mixtures of optimism and pessimism of the world ahead. Jews who were in awe of speed, energy, and light- imagined boldly and used creativity to repair what was they saw as broken in their time. They were asking the same or similar futurist questions we ask now, but with varying intentions:How do we sanctify technology? How do we balance innovation with ethics? How can art and design deepen our connection to our values rather than distract from it?

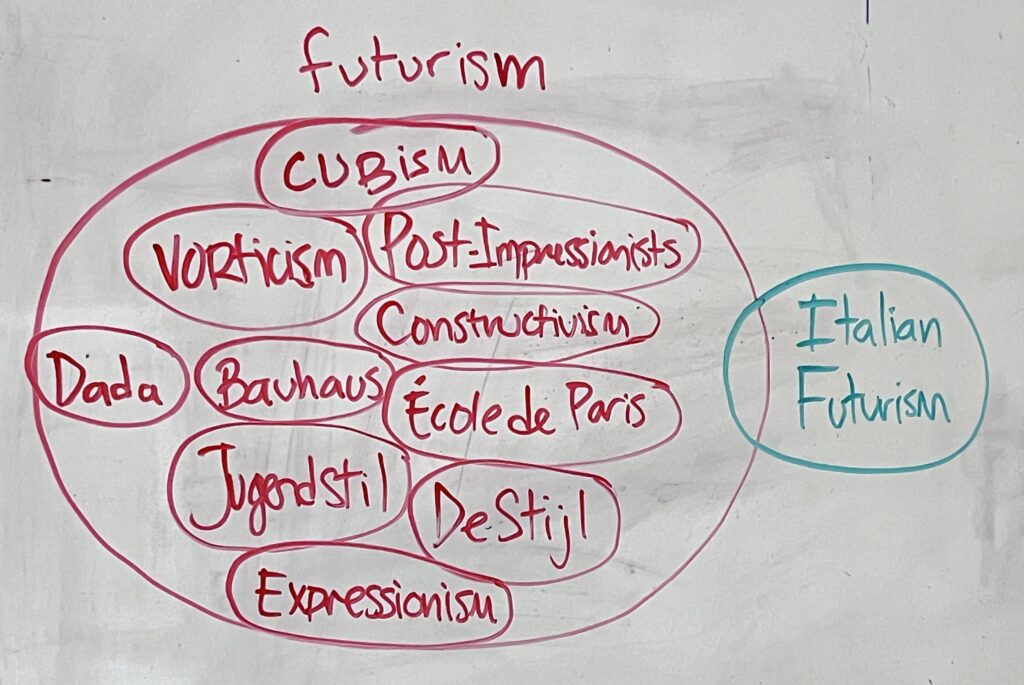

But unlike other futurist movements, Jews were rarely gathered under one banner. In the eighteenth through twentieth centuries, they were often distributed participants within the world’s avant-garde movements.

They were scattered across modernism, abstraction, and science fiction. Jewish artists and thinkers helped define of futurist leaning movements like Cubism, Vorticism, Constructivism, Art Nouveau (Jugendstil), the Bauhaus, comics, science, cinema, and technology, yet they entered these movements as outsiders, navigating exile, assimilation, and the tension between belonging and vision.

In contrast, Jewish futurism, then, is a reunion of that diaspora. It’s a collective recognition that Jewish creativity has always been dispersed, but futurist. Our task now is to connect those remote sparks into a shared constellation.

Jewish futurism, as I understand it, isn’t about breaking from tradition, it’s about revealing the through line of Torah, design, and imagination. The real work is to dialogue with this evolution together. Our ancestors did it through parchment, pigment, and print. We do it through pixels, algorithms, and immersive light.

This essay is an attempt to trace that lineage by identifying the people and moments, ancient and modern, that carried the qualities of Jewish futurism before we had words for it.

2. Prophets and Visionaries: The First Jewish Futurists

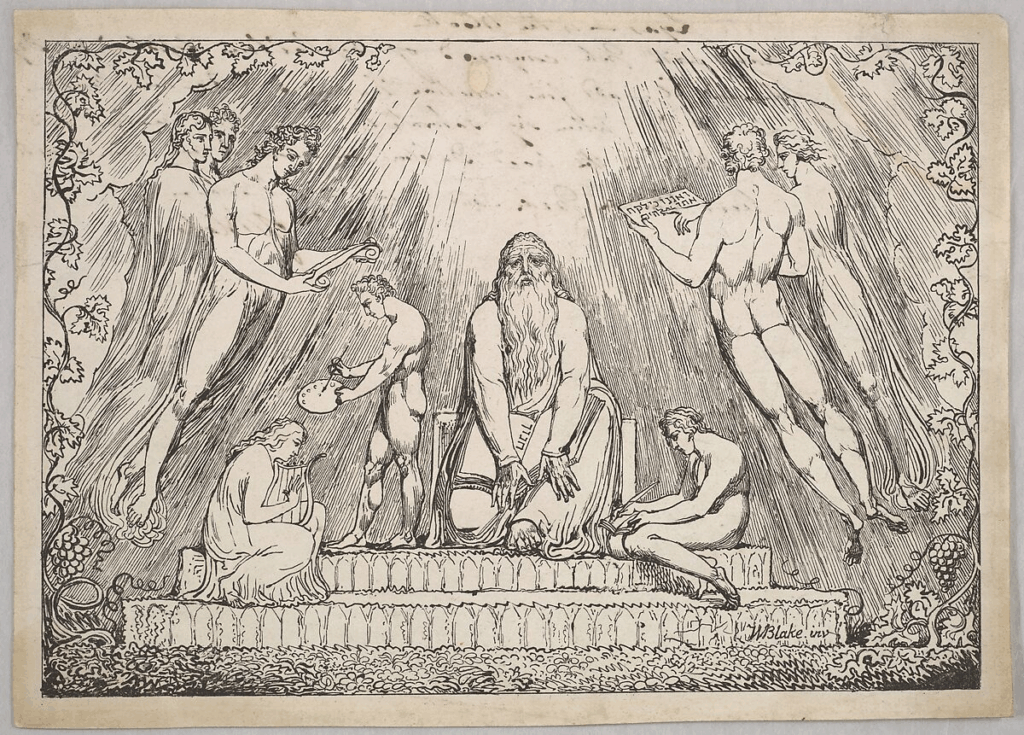

The Jewish imagination has always been forward-looking and possessed the virtues of futurist thought. Many stories in the Torah show characters facing grave challenges who reluctantly, yet diligently, press onward toward many future promises. Isaiah dreamed of a world where swords would become plowshares (Isaiah 2:4), reimagining technology as an instrument of peace rather than domination. The non-canonical, Book of Enoch envisioned the celestial ascent of a very minor Torah character, an early meditation on transformation and transcendence.

These were not myths of escape but frameworks for moral invention and prototypes of a better world.

The Torah itself ends in anticipation when Moses glimpses the Promised Land but never enters. The Jewish story begins by looking at the horizon toward a promise deferred, yet always pursued. That restless hope is also in the DNA of Jewish Futurism.

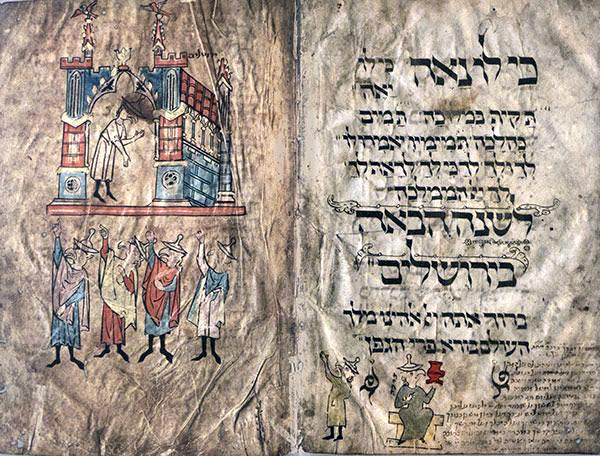

3. “Next Year in Jerusalem”: Our First Futurist Statement

The phrase L’shanah haba’ah b’Yerushalayim, Next year in Jerusalem, has always been the ultimate Jewish futurist phrase. It is both prayer and design challenge. It asks: what will it take, ethically and creatively, to build the world where that hope becomes real?

Jerusalem is not only a city but a symbol of the convergence of heaven and earth, ethics and aesthetics, faith and form. Every Jewish generation has tried to construct its own version of it. Jewish Futurism is our turn to do the same, using the tools and technologies of our age to reimagine what Jerusalem might mean tomorrow.

4. Mystics, Makers, and the Ethics of Revelation

Centuries later, the mystics of the Zohar built the first great Jewish model of complexity. Attributed to Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, the Zohar describes creation as a system of divine emanations, the Sefirot, a network of energy, feedback, and interdependence that sounds remarkably like a precursor to modern systems or network theory.

An even earlier mystical text, the Hekhalot Rabbati, contains the story of the Sar HaTorah, the “Prince of Torah.” In it, a rabbi summons an angelic teacher to grant him instant divine wisdom. The revelation overwhelms him beyond capacity, leaving him nearly destroyed. The angel warns that knowledge received without readiness shatters the vessel. This is not a warning against study, but a parable about integration, teaching that divine insight requires ethical preparation, humility, and spiritual maturity.

This early mystical story prefigures a central idea of Jewish Futurism: revelation without discipline leads to collapse. Innovation, like wisdom, must be tempered by moral structure.

A few centuries later, in Safed, Isaac Luria (the Arizal) and his circle extended that vision, transforming cosmic trauma into design theology. Their concept of Tikkun Olam, repairing the world, framed healing not as an abstract ideal but as an iterative process of creation and refinement. The Kabbalists turned Divine catastrophe, the shevirat ha-kelim or shattering of vessels, into a blueprint for human creativity, a call to rebuild with intention.

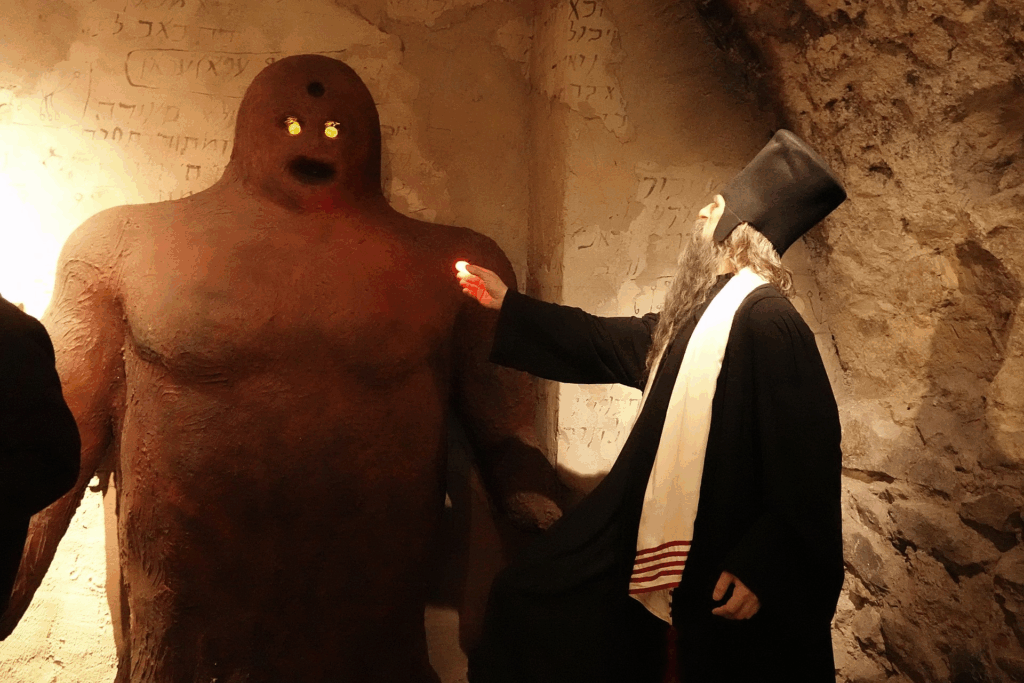

In the same spirit, Rabbi Judah Loew of Prague gave shape to one of Judaism’s most enduring myths of technological creation, the Golem, a being formed from clay and animated through sacred language. The Golem’s body was innovation, its control was halakhah. It remains Judaism’s first meditation on artificial life, automation, and moral limits, what we now call the ethics of technology.

Together, these three sources, the Zohar’s vision of divine networks, the Sar HaTorah’s warning about unintegrated revelation, and the Golem’s lesson in ethical creation, form the foundation of Jewish Futurism. They map the two coordinates that still define our creative practice today: creation as systems design, and ethics as the boundary of holiness.

5. Enlightenment, Utopia, and Early Jewish Design

The 19th and early 20th centuries brought the industrial age, and with it, new Jewish imaginings of the future. Theodor Herzl’s Altneuland (1902) offered not just political

Zionism but a speculative blueprint of his vision of a technologically advanced society guided by justice. Ephraim Moses Lilien, often called the “first Zionist artist,” translated Herzl’s ideas into visual form, merging Art Nouveau (Jugendstil) beauty with prophetic idealism.

Around the same time during late Ottoman period (1906) and into British Mandate rule, Boris Schatz founded the Bezalel School of Art and Design in Jerusalem.

He believed that Jewish creativity could rebuild both spirit and society and was a major shaper of the Zionist art movement. The school fused European aesthetics, often brought by fleeing Jewish practitioners, with biblical themes, teaching the essence of Hiddur Mitzvah, beautifying the mitzvah.

The Bezalel School was the first organized institutional embodiment of Jewish Futurism making art and design as acts of national and spiritual renewal.

1. Futurism vs. futurism: Origins and Overlaps

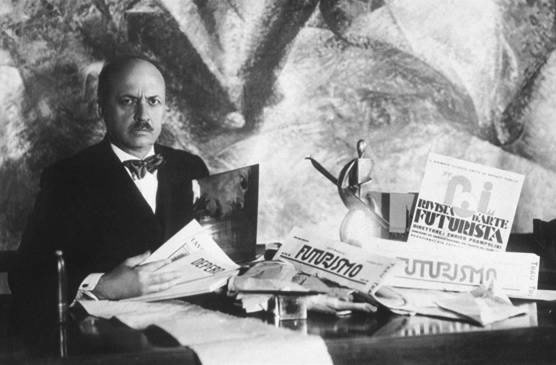

Futurism (capital F) was first coined as an art movement name by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti in 1909. His Futurist Manifesto, published in Le Figaro, announced a radical social ideology backed by an aesthetic devoted to speed, light, energy, and the mechanical beauty of modern life. Artists such as Umberto Boccioni, Giacomo Balla, and Gino Severini sought to capture motion and power in a new visual language for the twentieth century. Yet as the movement matured, its rhetoric of destruction and renewal fused with Italian nationalism and ultimately fascism, turning artistic innovation into ideology.

One adjacent Jewish figure, Margherita Sarfatti, an art critic and Mussolini’s cultural adviser, championed early Futurist ideals while stressing that art must bridge past and future, not obliterate tradition. When fascism hardened, she was expelled from Italy under the racial laws, exposing Futurism’s fatal contradiction — a vision of progress that devoured its own makers.

By contrast, futurism (lowercase f) describes the broader impulse toward innovation that surfaced across Europe under other names: Vorticism in Britain, Constructivism in Russia, and the Bauhaus in Germany. The same fascination with machines, energy, and new media became, outside Italy, a moral and creative language for modern life.

The groundwork for all of these movements was laid by proto-futurists — visionaries who imagined the future before it had a name. Jules Verne and H. G. Wells wrote of flight, electricity, and space travel. Scientists and photographers Étienne-Jules Marey and Eadweard Muybridge dissected motion through sequential imagery.

Philosophers Henri Bergson and Friedrich Nietzsche, along with Symbolist poets, infused culture with ideas of vitality, time flux, and transformation that would animate futurist art decades later.

Although none of these early futurists were Jewish, Jewish innovators shaped the technological world that made Futurism possible. Albert Einstein’s relativity redefined time and space.

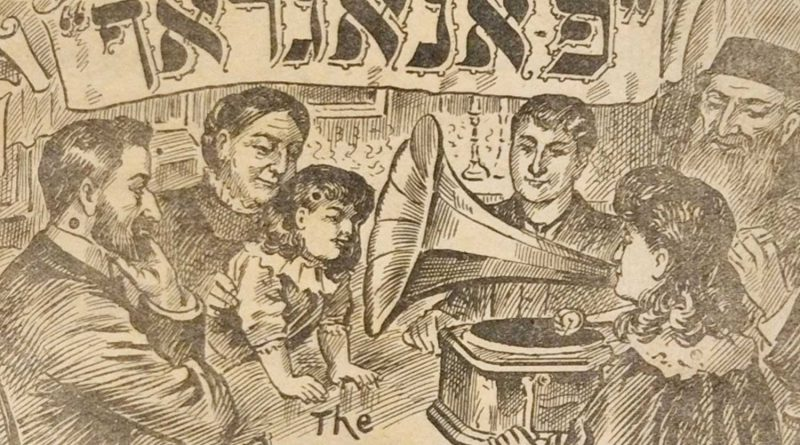

Emil Berliner invented the gramophone making it possible for Jewish sound and oral tradition to be archived and disseminated globally for the first time; Charles Adler Jr. created the traffic-signal system that organized modern cities.

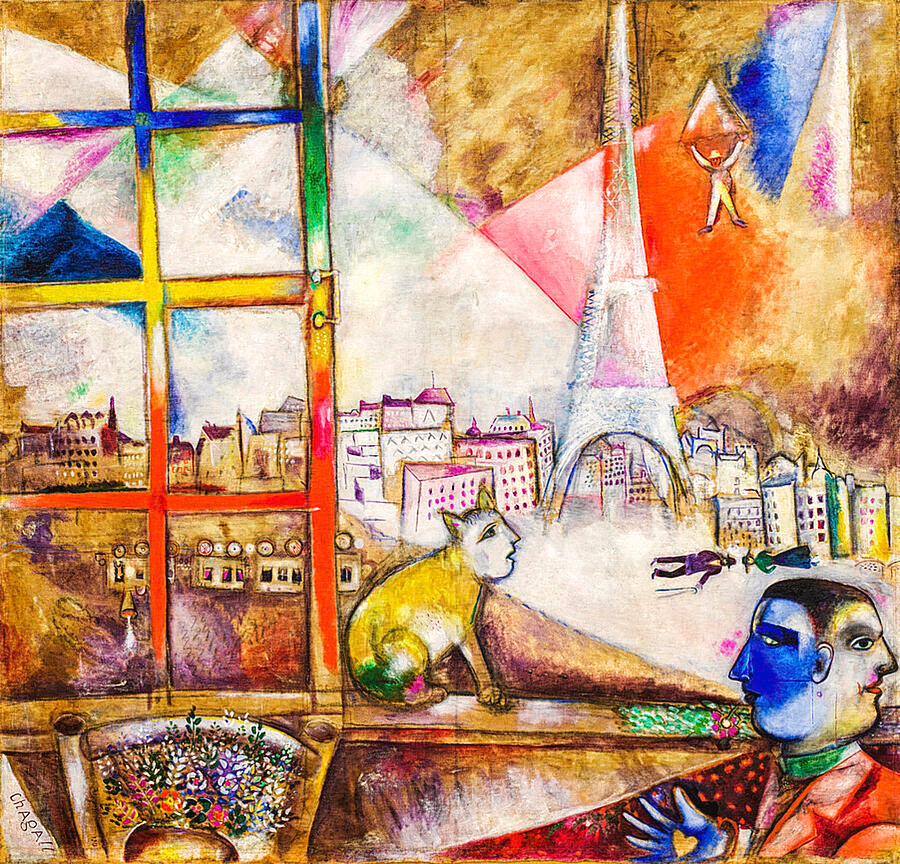

In the arts, Jewish modernists such as Marc Chagall and Jacques Lipchitz extended Cubist abstraction into spiritual allegory, transforming the language of modernism into a vessel for transcendence. Chagall, especially in his Paris period, reimagined futurism not as mechanical speed but as illumination and ascent. Paintings like Paris Through the Window (1913)

and The Eiffel Tower (1911) shimmer with the chromatic pulse of electric light, fracturing the modern city into simultaneous layers of time, memory, and dream.

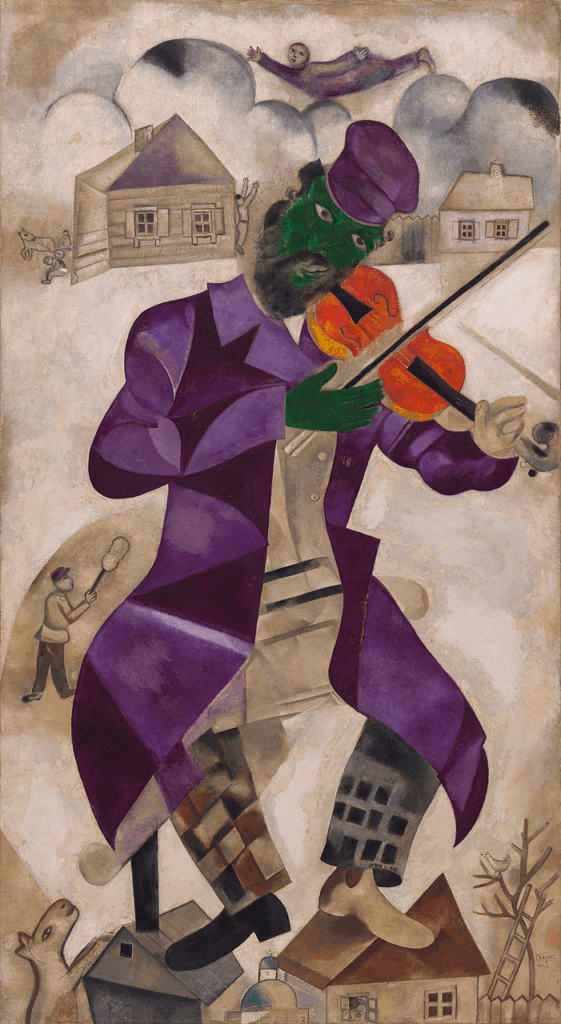

His Violinist series vibrates with musical energy rendered as color and form, suggesting that sound itself could become a visual current. In Chagall’s hands, the machine age becomes a theater of revelation—modernity recast as a mystical experience of motion, radiance, and spiritual flight.

Jacques Lipchitz, working in sculpture, carried this vision into three dimensions. His early Cubist bronzes such as Man with a Guitar (1915) and Flight (1918) dissolve the human form into rhythmic, interlocking planes that seem to oscillate in space. Rather than glorifying machinery, Lipchitz sought to capture the vital energy and inner light of movement itself. Both artists turned Cubism’s structural analysis into a Jewish futurism of rhythm and spirit, where motion was not domination but devotion, and modern form became a bridge between earth and heaven. And in Britain, David Bomberg fused modern geometry with prophetic vision. Bringing a softer humanism to the abstract modernist aesthetics of Vorticism, the UK cousin of Futurism.

His painting The Mud Bath (1914) exemplifies the mechanical rhythm of Vorticism, while The Vision of Ezekiel (1912) merges machine aesthetics with biblical wonder. For Bomberg, the mechanical and the mystical share a single pulse — creation itself.

A telling example is Margherita Sarfatti (1880-1961), the only female member associated with the Italian Futurism art and design movement (1909-1944), was Jewish, an art critic and intellectual. She once championed the movement’s early aesthetics of speed and even personally advised Mussolini as well as being his mistress.

While Sarfatti’s writings do not emphasize her Jewish background, they articulate a sustained belief in modernity that is anchored in continuity that art must recall and transform tradition, not demolish it. In her words: “This idea of art as a bridge from past to future aligns with the broader notion of futurism not as mere disruption but thoughtful renewal.”Her reviews and essays would propel the Futurist movement to a national level.

Image via source

When fascism hardened in 1938, she was expelled from Italy for being Jewish. Her story encapsulates the fate of many Jewish modernists: contributors to cultural innovation, later rejected by the very movements they helped inspire.

5. Modernism and the Avant-Garde: Lissitzky to the Bauhaus

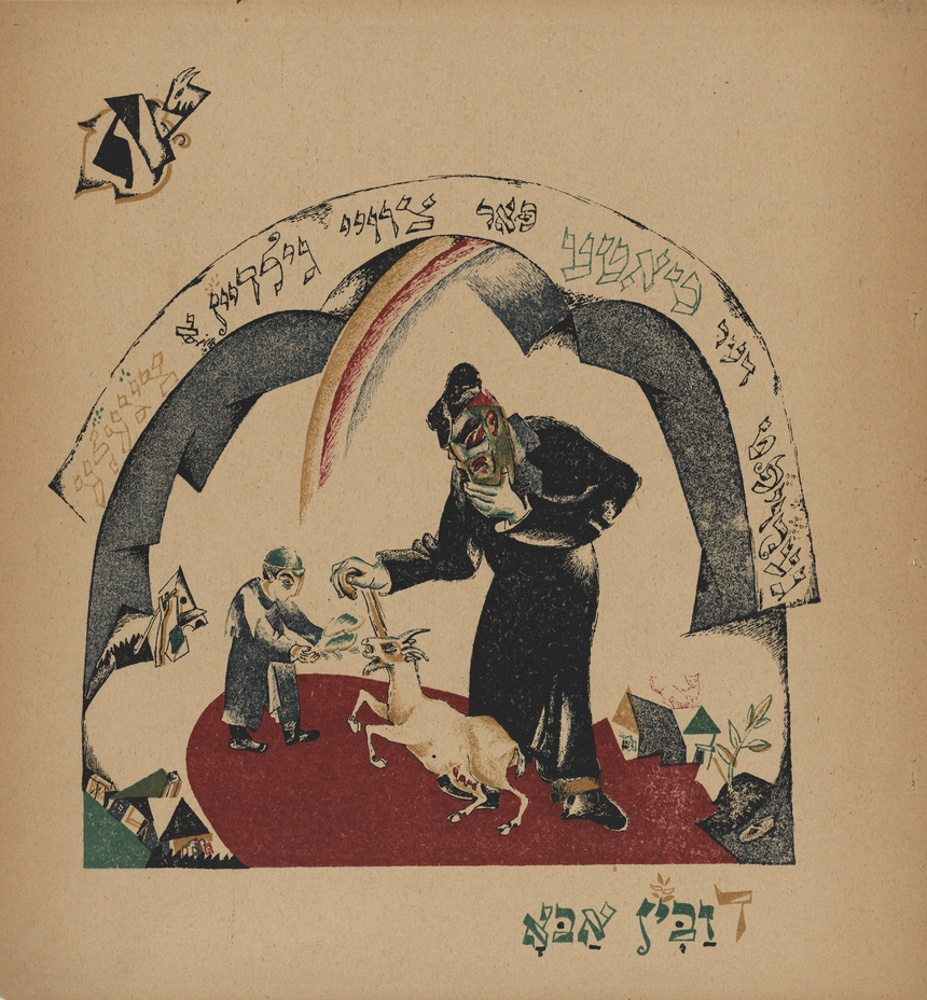

In Eastern Europe, El Lissitzky carried Jewish visual tradition into modernism. His 1919 lithographs for Had Gadya reinterpreted Passover through Constructivist abstraction,

using geometry as theology. His phrase, “The goal is Jerusalem,” perfectly captured the Jewish Futurist impulse: the messianic hope rendered through design.

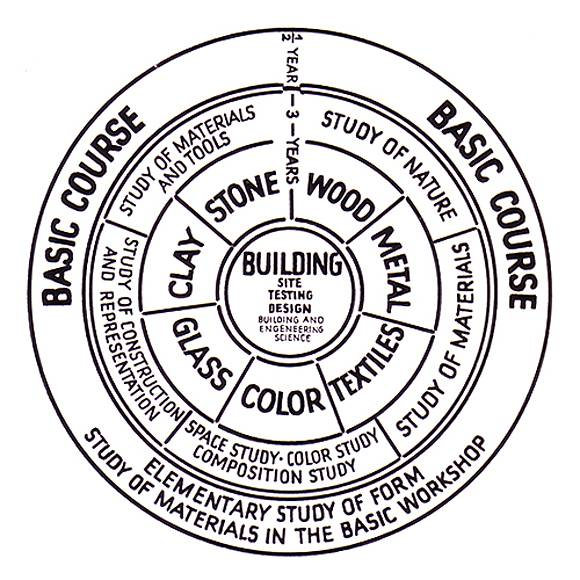

At the Bauhaus Design school(Germany 1919-1933), Jewish artists such as painter and photographer László Moholy-Nagy, architect and designer Marcel Breuer, and textile artist and printmaker Anni and Josef Alberses continued this lineage.

They believed design could uplift society through clarity, functionality, and light. Through their curriculum of studying various materials, these educators echoed the rabbinic principle bal tashchit (do not waste) and the mystical pursuit of the illumination of ideas in visual and functional forms that solve problems as well as dialogue with beauty.

Their classrooms were secular temples of Tikkun Olam: ethical creativity as public good.

6. Mythmakers: Sci-Fi, Comics, Cinema

Jewish imagination found new life in mass media, Especially in science fiction writing, comics, and cinema, where exile and ethics could hide in plain sight.

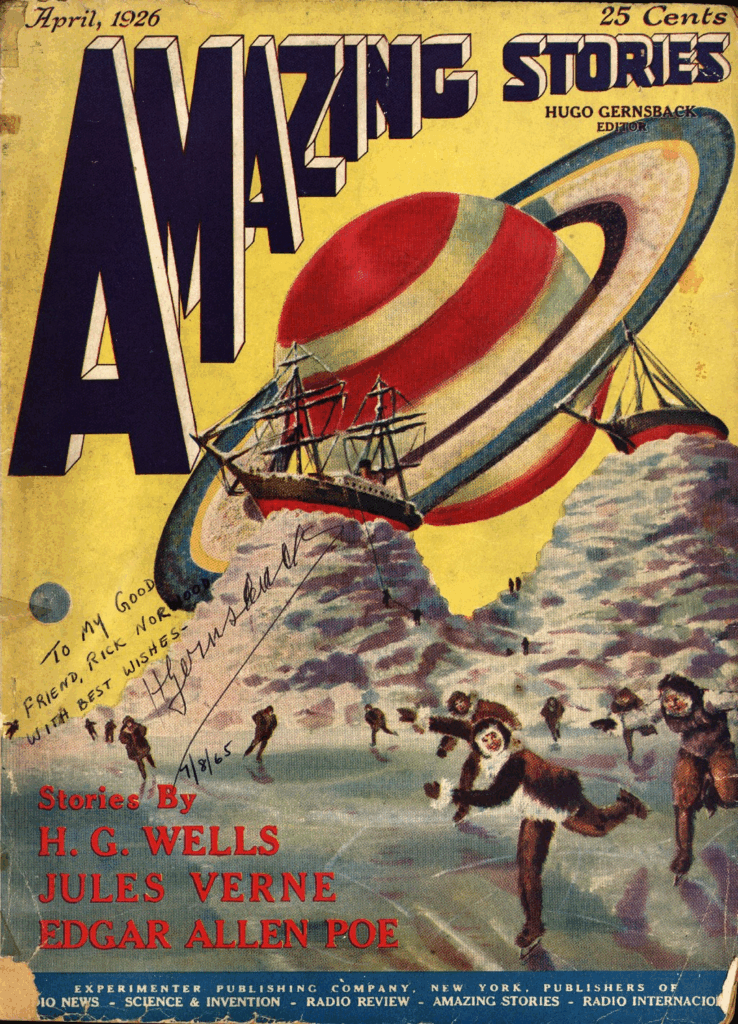

As modernism gave way to the machine age, a new arena for Jewish imagination emerged in the world of pulp magazines and speculative storytelling. In 1926, Hugo Gernsback, a Luxembourg-born Jew, founded Amazing Stories and coined the term

“scientifiction,” launching the modern science fiction magazine industry. Through his editorial vision, the future became a place to test human ethics as much as scientific progress.

Jewish writers soon filled those pages. Isaac Asimov, William Tenn (Philip Klass), Robert Sheckley, and Harlan Ellison turned speculative fiction into a moral and philosophical workshop. Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics echoed halakhic reasoning — codifying responsibility before creation. Tenn’s On Venus, Have We Got a Rabbi transformed Talmudic humor into cosmic commentary. Their stories asked enduring Jewish questions: What does it mean to create life? To act justly? To be human in a world of our own making?

The science fiction magazine became, in its way, a cosmic Mishnah on paper that featured serialized debates about ethics, invention, and destiny. In these pulp worlds, Jewish storytellers extended the prophetic imagination of Isaiah, Elijah, Enoch and the speculative daring of the Kabbalists into the age of electricity, rockets, and radio waves.

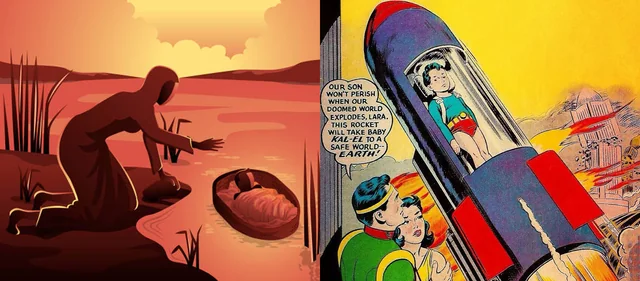

In 1938, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster created Superman: an alien refugee, morally bound to defend humanity. Though a very Moses-like framing, Clark Kent wasn’t explicitly Jewish.

Yet his story’s core themes of exile, justice, hidden identity, redemption, to echo the Jewish experience wrapped in universal myth.

At Marvel, Jack Kirby and Stan Lee filled their universe with wandering scientists and reluctant heroes. Their stories turned vulnerability into virtue. The Spider-Man line, “With great power comes great responsibility,” reads like Pirkei Avot for a new generation.

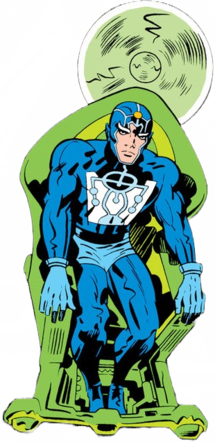

Kirby’s later series,The New Gods (1970-73), pushed further, turning superhero cosmology into visual midrash. His battles of light and shadow mirrored the Kabbalistic drama of creation and repair, while also superimposing a planetary level version of The Shoah, Holocaust. At that time, Kirby successfully introduced specifically Jewish originating super beings into the American comic book lexicon.

Notably, Metatron, an angel who Enoch embodied in his adventure through the four worlds of existence in Kabbalah, the Mother box– an Ark of the Covenant like container, the Mobius chair– a holy throne like object that has next level AI capabilities, and a boom tube– a merkaba, chariot-like, teleportation device.

These artists translated Torah’s moral code into pop language, giving the world a modern accessible form of Jewish prophecy.

Many times simultaneously, Jewish filmmakers carried that same prophetic imagination into cinema, using light, time, and narrative as tools for moral exploration. Stanley Kubrick reimagined the Golem story for the machine age, probing what happens when human creation outgrows moral control. In 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and in A.I. (2001), he questioned whether technology could ever mirror compassion, or like the Golem, it would always lack a soul. Though Steven Spielberg directed the movie, Kubrick originally had the rights and was developing the A.I. movie before his death in 1999.

Sidney Lumet turned the courtroom and newsroom into ethical laboratories. In 12 Angry Men and Network, justice and conscience collide with ego, power, and fear. His films translate lo ta’amod al dam re’echa, “do not stand idly by”, into an embodied principle of characters wrestling with justice. Darren Aronofsky brought Kabbalah, gematria and psychology into direct conversation, finding mysticism in mathematics in Pi, and cosmic yearning in The Fountain and Noah. Ari Folman, through animation, examined how memory and trauma shape moral responsibility in Waltz with Bashir and The Congress.

Meanwhile, the Coen Brothers and Joseph Cedar turned irony and uncertainty into spiritual inquiry. Their stories unfold like modern Mussar mini-dramas of human frailty tested by fate. Mel Brooks reclaimed film genres that once erased Jewish presence, proving laughter itself can be an act of tikkun, repair.

Across their films, the same Jewish questions resurface: What does it mean to be responsible for the world you’ve made? Can imagination redeem suffering? These filmmakers transformed those questions into a universal visual language that wove Jewish ethics, paradox, and hope into the cinema’s shared dream.

7. Jewish Thinkers of Media and Technology

As technology reshaped culture, Jewish thinkers were among the first to ask how it changed human perception. In 1933, German-Jewish philosopher, Walter Benjamin questioned how the mechanical reproduction of photography altered our sense of the sacred, almost anticipating today’s debates about ethical AI use and authorship.

He deeply questioned the aura of an object by exploring our emotions surrounding originality, creativity and human desire.

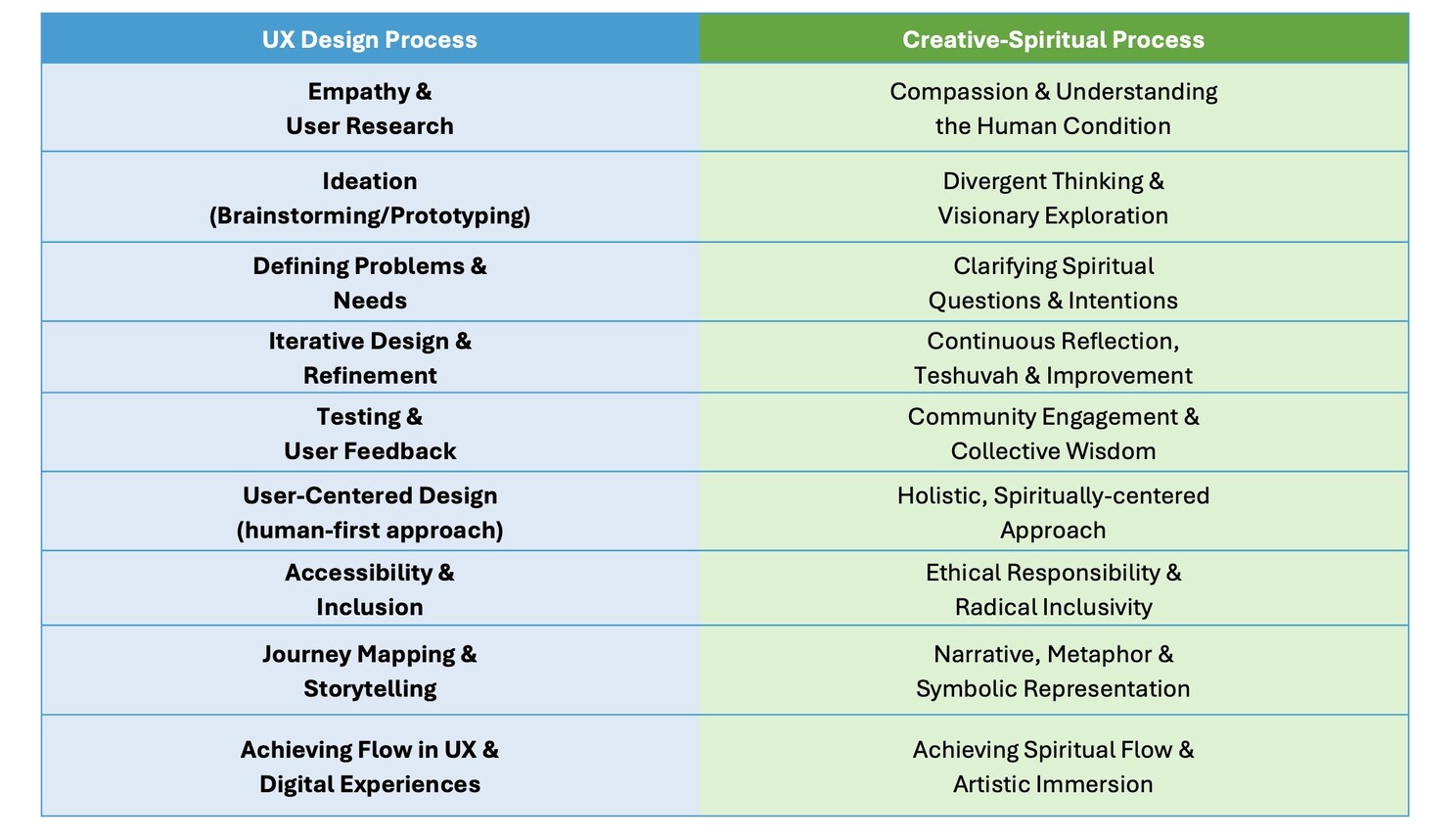

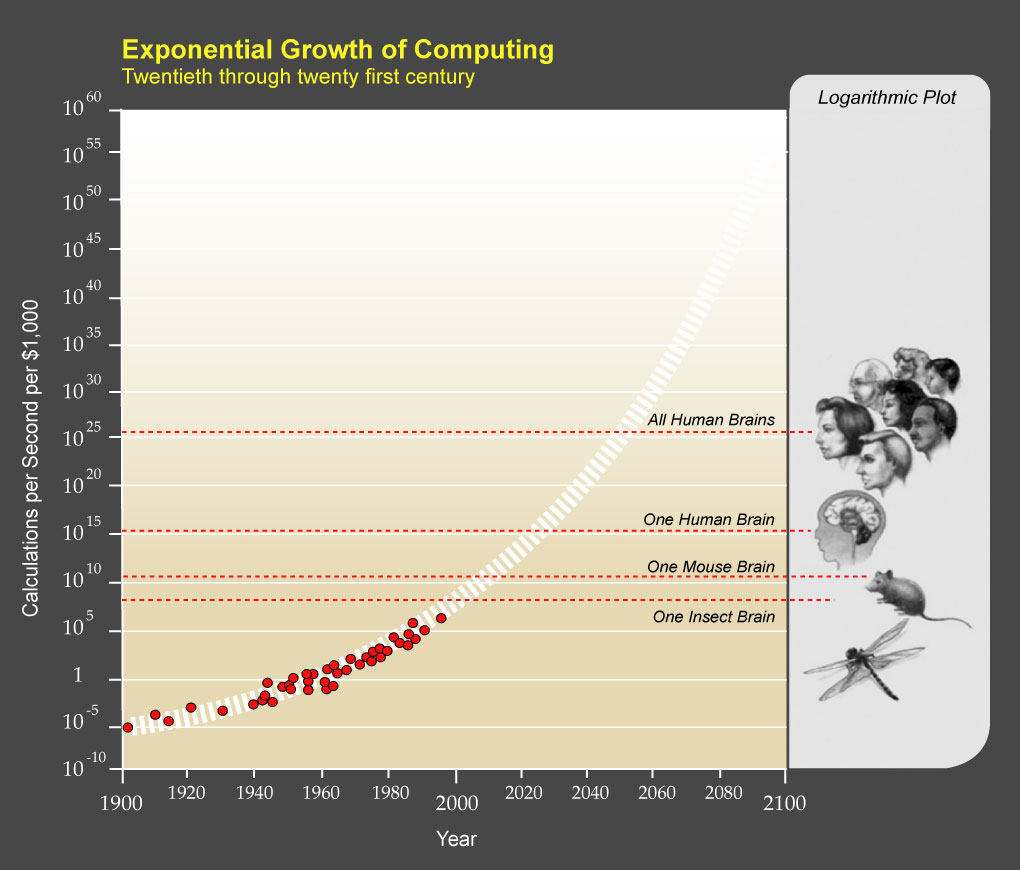

At the birth of the internet age, Lev Manovich analyzed digital media as a new textual form, understanding databases and user-interfaces to function like Talmudic commentary, where meaning emerges through interaction and dialogue. Ray Kurzweil reimagined transcendence through technology, envisioning the “singularity” when humans merge with machines. I see this as a secular echo of the Kabbalistic longing for devekut, union with the Divine. Yet where mysticism seeks connection through personal refinement, Kurzweil imagines it through building our technical and intellectual abilities.

Revealing both the similarity and the danger of modern transcendence without ethics. And educators like Ari Waller continue to explore how design and interactivity can transform Jewish learning for a digital age.

Together, they extend the Jewish tradition of commentary into the domain of code.

8. Standing in a Chain of Builders

Looking back, it’s clear: Jewish Futurism has always existed in spirit, even if it didn’t have a name. It’s the instinct to design with conscience, to imagine with ethics, and to translate Torah into form.

We stand on the shoulders of those who used story, structure, and symbol to envision better worlds. They left us blueprints that are sometimes literal and sometimes mystical. Our task is to read them carefully and continue the work.

To innovate without memory is to build a Golem. To create without conscience is to call down the Sar HaTorah unprepared. But rather to design with kavvanah and tzedek, intention and justice, is to join the same futurist lineage that began at Sinai.

9. The Present Continuum: Art, Design, and Collective Vision

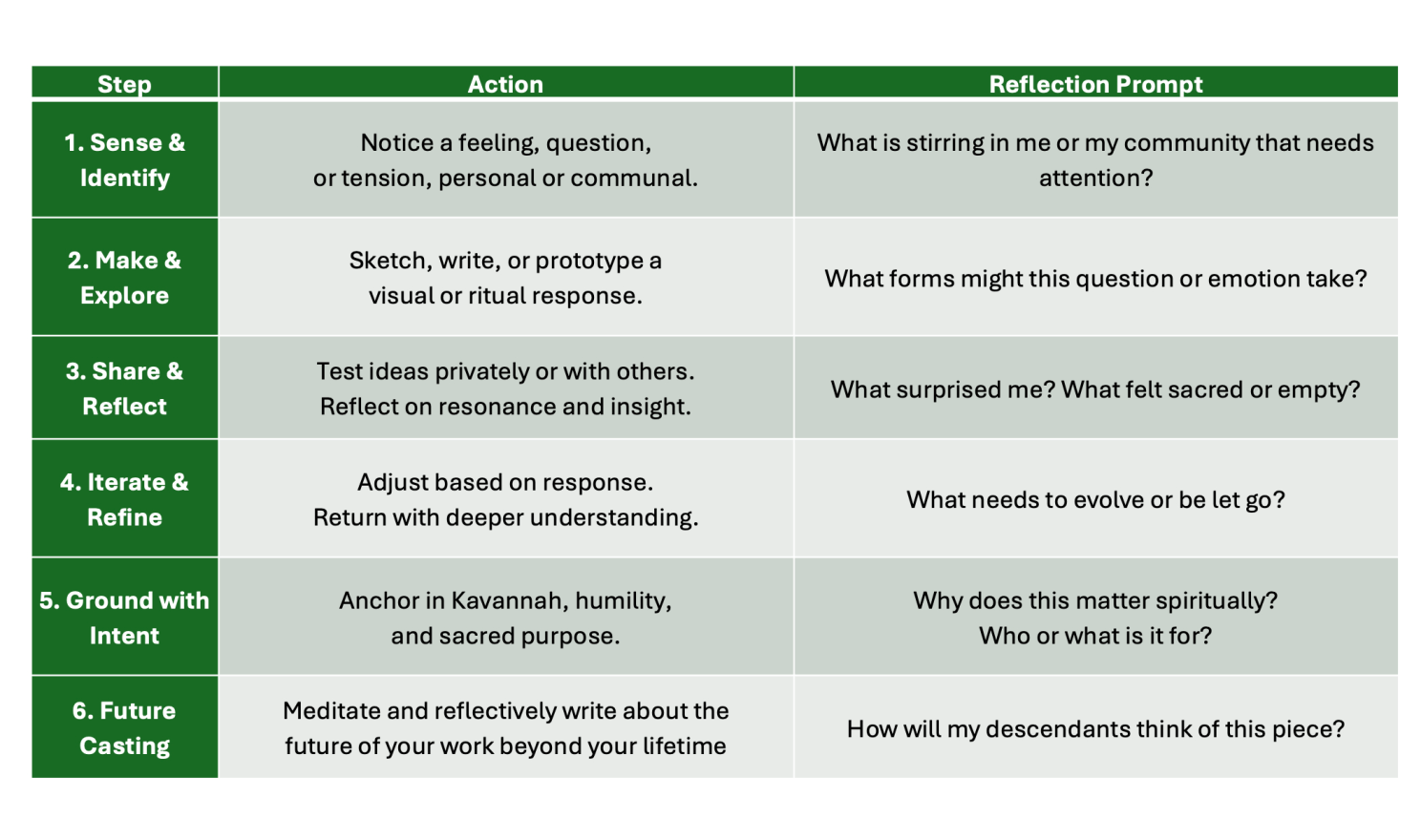

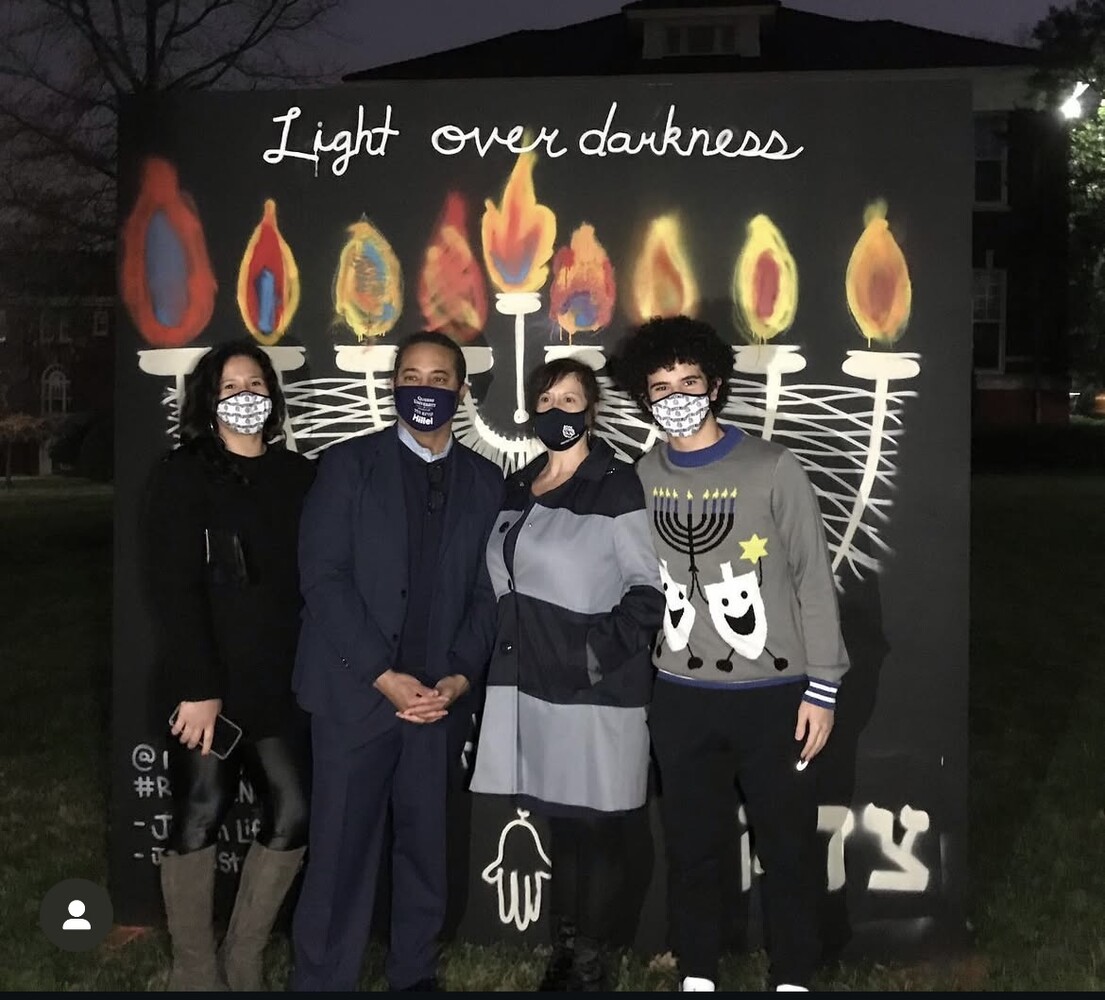

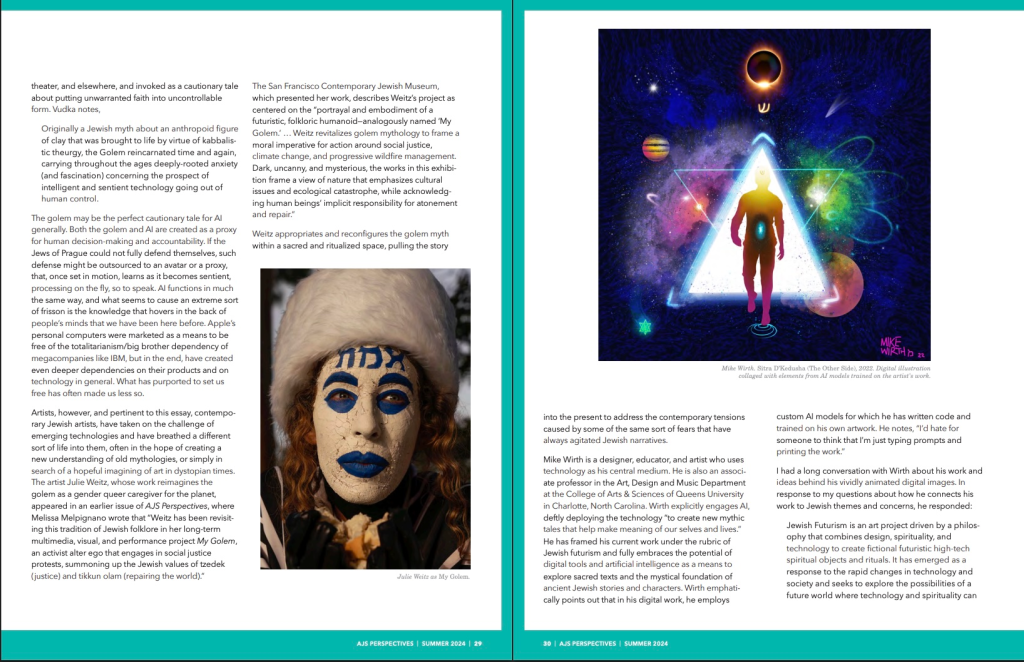

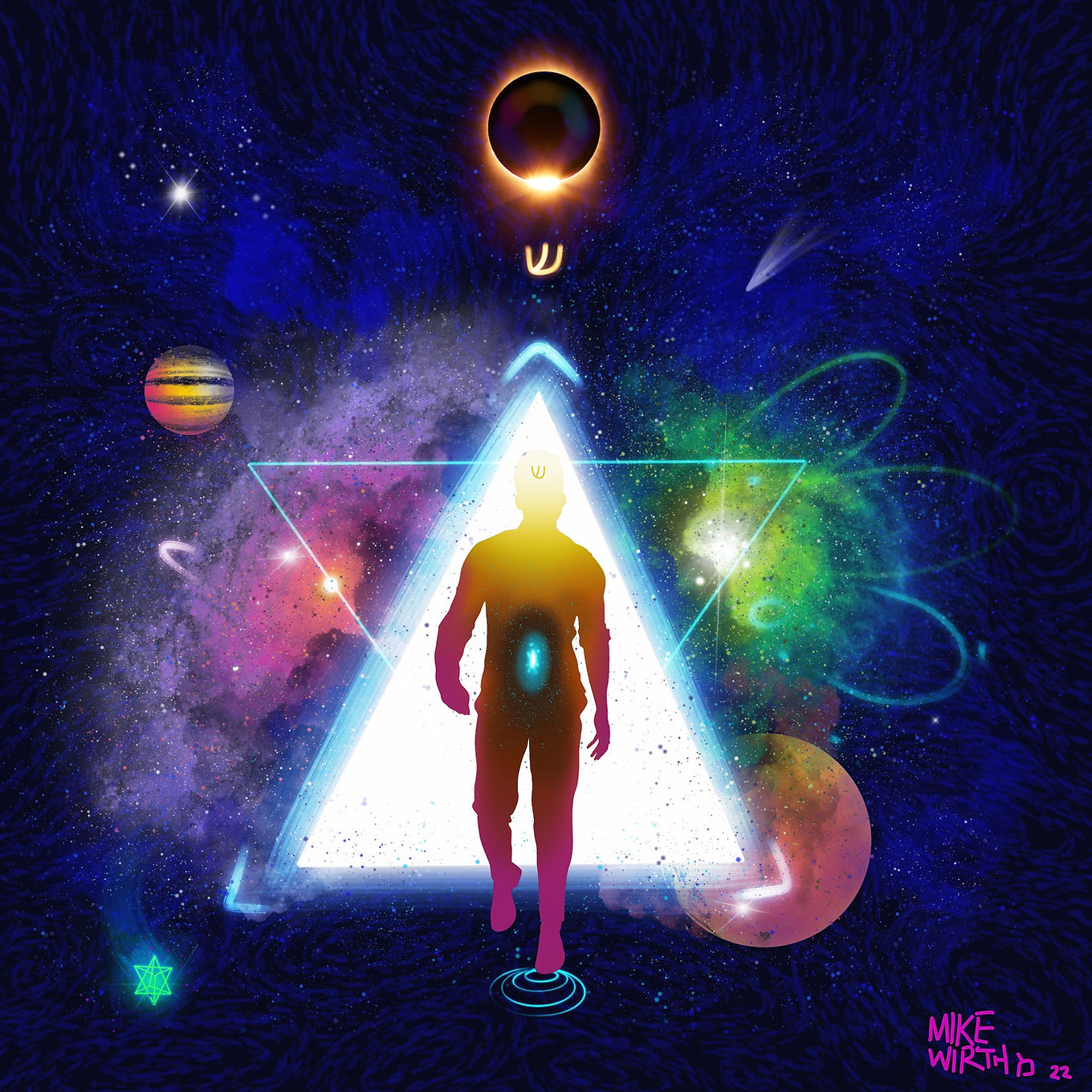

Today, artists, designers, and technologists continue that same conversation. My own work in digital art, murals, and the Hiddur Olam project is part of that continuum, a lineage of Jewish creativity that treats design as an act of devotion and world-building. I see AI not as a threat but as a kind of Sar HaTorah, a force that can offer insight if met with readiness and humility. Like the artisans of the Mishkan, I believe design becomes sacred when it channels empathy, restraint, and intention.

In 2022, I presented my philosophy and artwork of Jewish Futurism at the Conney Art Conference and later gave a live presentation at the JADA Art Fair during Miami Art Week. Both experiences reminded me how many Jewish creators are already working toward this shared vision—each in their own medium, each blending tradition with technology.

That same year, I debuted my ongoing project Rimon: The Cosmogranate, a digital and physical artwork exploring creation, fragmentation, and repair through interactive design. The piece reimagines the pomegranate—a symbol of divine abundance—as a cosmic interface, linking Kabbalistic symbolism with data visualization and immersive art. Rimon became a practical expression of my Jewish Futurist framework: systems thinking meets sacred storytelling.

Since then, I’ve met writers, digital artists, collage-makers, jewelers, and illustrators who are all exploring what Jewish creativity can mean in the twenty-first century. I’d love to meet them all, to learn what they’re building, and to be in conversation. There are also scholars whose work leans more toward theory than creative practice, but they’re vital too. This movement needs everyone: makers, thinkers, builders, and interpreters.

Together we form a creative ecology of imagination and insight that reaches across generations and disciplines, connecting our past to our unfolding future.

No one can pursue this vision alone. There needs to be a gathering of like-minded Jewish Futurists, artists, technologists, scholars, and dreamers, willing to experiment together. A community that treats innovation as avodah, sacred service, and technology as a tool for renewal rather than disruption. Through shared projects, symposia, and creative residencies, we can imagine and prototype what a Jewish future might look and feel like, rooted in text, tradition, and ethics, but alive with invention.

Jewish Futurism is not about predicting the future. It’s about designing the future, ethically, communally, and beautifully. It is a collective project, not an individual quest. The middah of Areyvut, mutual responsibility, is its foundation.

Every Jewish artist, from Isaiah to Lissitzky, from Herzl to Kirby, from Bezalel to Bauhaus, from Benjamin to Manovich, has been part of that same dialogue, how to turn imagination into justice, light, and meaning. Jewish Futurism invites us to take up that question again, not to escape the past, but to reimagine it as raw material for redemption.

Jewish Futurism isn’t a trend. It’s an inheritance and a responsibility. We’re not just imagining what comes next. We’re continuing a project that began with the words: Let there be light.

Works Cited

Aronofsky, Darren, director. Pi. Artisan Entertainment, 1998.

—. The Fountain. Warner Bros., 2006.

—. Noah. Paramount Pictures, 2014.

Benjamin, Walter. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Translated by Harry Zohn, Schocken Books, 1969.

Blake, William. Enoch. 1806–07, Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org.

Brooks, Mel, director. The Producers. Embassy Pictures, 1967.

Coen, Joel, and Ethan Coen, directors. A Serious Man. Focus Features, 2009.

Edelmauswaldgeist. Golem Depicted at Madame Tussauds in Prague. Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Folman, Ari, director. Waltz with Bashir. Sony Pictures Classics, 2008.

—. The Congress. Drafthouse Films, 2013.

Gernsback, Hugo. Amazing Stories, vol. 1, no. 1, 1926.

Gropius, Walter. Bauhaus Curriculum Chart. 1922.

Herzl, Theodor. Altneuland. Hermann Seemann Nachfolger, 1902.

Kirby, Jack, and Mike Royer. New Gods #5. DC Comics, Nov. 1971.

Kubrick, Stanley, director. 2001: A Space Odyssey. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1968.

Kurzweil, Ray. “The Law of Accelerating Returns.” Kurzweil Technologies, Inc., 2001, https://www.kurzweilai.net.

Lilien, Ephraim Moses. Theodor Herzl in Basel. 1901, Wikimedia Commons.

—. Logo of The Bezalel School. 1906, Wikimedia Commons.

Lissitzky, El. Had Gadya. 1919, Wikimedia Commons.

Lumet, Sidney, director. 12 Angry Men. Orion-Nova Productions, 1957.

—. Network. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1976.

Manovich, Lev. The Language of New Media. MIT Press, 2001.

Mattioli, Massimo. “For a Correct Relocation of Margherita Sarfatti.” Finestre sull’Arte, https://finestresullarte.info/en/books/for-a-correct-relocation-of-margherita-sarfatti-massimo-mattioli-s-pamphlet.

Merian, Matthäus. Ezekiel’s Vision. 1670, Wikimedia Commons.

Sarfatti, Margherita. Collected Writings on Modern Art and Futurism. Editoriale Domus, 1930.

Schatz, Boris. The Bezalel School of Arts and Crafts. Jerusalem, 1906.

Spielberg, Steven, director. A.I. Artificial Intelligence. Warner Bros., 2001.

Victorgrigas. Crowd Shoots Photo of the Mona Lisa at the Louvre. 2014, Wikimedia Commons, CC ASA 4.0.

Waller, Ari. “Interactive Design and Jewish Education in the Digital Age.” Jewish EdTech Review, 2023.

Wirth, Mike. “A Brief History of Jewish Futurism.” Charlotte Muralist: Mike Wirth Art, 2 Nov. 2025, https://mikewirthart.com/a-brief-history-of-jewish-futurism/.

—. “Stop Using AI As a Hammer, When It’s a Screwdriver: My AI Odyssey Through the Classroom.” Charlotte Muralist: Mike Wirth Art, 14 June 2025, https://mikewirthart.com/stop-using-ai-as-a-hammer-when-its-a-screwdriver-my-ai-odyssey-through-the-classroom/.

—. Rimon: The Cosmogranate. 2022, Digital and Physical Artwork.