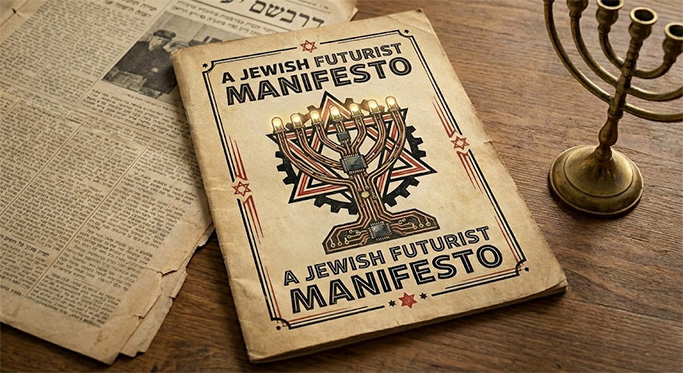

Introduction: Why a Jewish futurism Manifesto

Almost every modern era or movement of art has announced itself with a manifesto to declare what must come next. Often these manifestos of the past were blustery often spoke in the language of conquest. Most notably, the Italian Futurists (1909-1943) text glorified war, destruction, and exclusion of certain types of people. Unfortunately, their call for progress came at the expense of compassion and aligned themselves with fascism and antisemitism. For more insights, please read the previously wrote about the warnings that we can head from Italian Futurism in this article. Others defined themselves by what they rejected, not by what they hoped to heal.

I wrote The Jewish futurism Manifesto as an act of tikkun, to repair that lineage. It reclaims the idea of the manifesto as a sacred, inclusive, and ethical declaration of creative purpose. Where earlier manifestos worshiped speed and dominance, this one turns toward kavvanah (intention), chesed (compassion), and tzelem Elohim (the divine image in all). Read more about Mussar, Jewish ethics here.

We stand at a new threshold: between text and code, between human and machine, between memory and invention. Judaism, with its deep traditions of questioning, balance, and ethical creation, offers precisely the framework that modernity has lacked. This manifesto emerges from that realization that art, design, and technology can be Jewishly spiritual, halakhic, and humane.

Where other groups intended to shatter, we intend repair. Where others sought power, we seek presence. Jewish futurism is not rebellion for its own sake, but a recommitment to the creative covenant that began at Sinai. To make the world more beautiful, conscious, and just.

Throughout history, Jewish creativity has emerged in response to the extremes of its age. The Kabbalists of Safed (Tzfat, Israel) turned exile into cosmic repair; the artists of the Haskalah transformed enlightenment into moral awakening. From illuminated manuscripts to, the printing press, to digital light, Jews have continually reimagined how revelation meets reality. Jewish futurism continues this lineage, translating timeless values into the language of design and technology. It sees every tool, from ink to algorithm, as part of the same creative inheritance, each awaiting sanctification. Ours is not a rupture from tradition, but its renewal in the medium of the future.

The Manifesto

The Future is Jewish

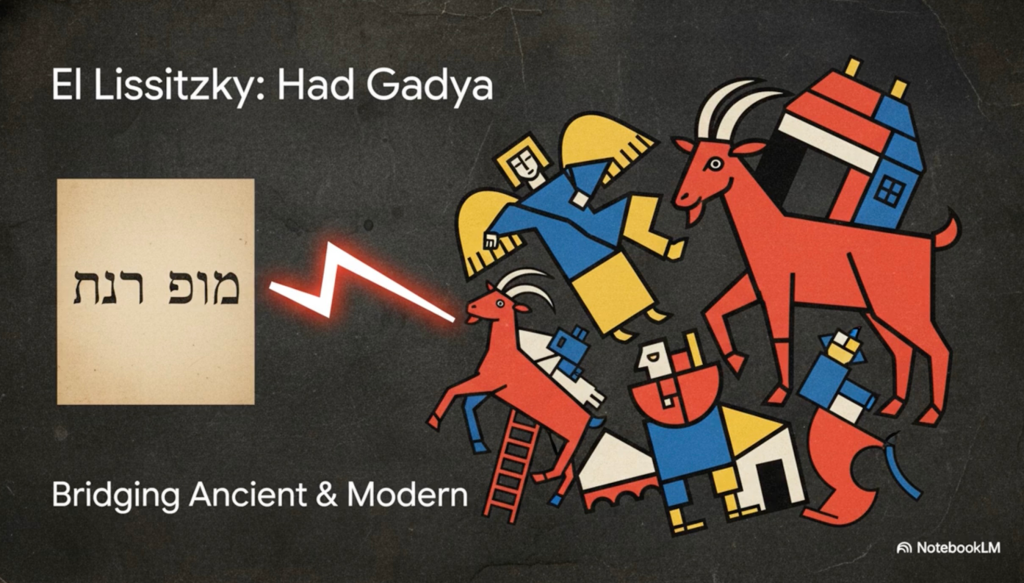

Jewish futurism envisions a world where Jewish wisdom, art, and halakhah evolve in dialogue with technological creation. We reject nostalgia as fear disguised as reverence. Tradition is not a cage but a scaffold for renewal. Jewish identity thrives through adaptation, spanning from parchment to print, from diaspora to data. We imagine futures where Torah and technology are not opposites but partners in creation. The Jewish future is not going to be inherited, it needs to be designed.

Sar HaTorah vs. Golem Mindset

Jewish futurism begins where two myths meet: the Sar HaTorah, the angel of instant wisdom, and the Golem, the creature of blind obedience. One represents revelation without readiness; the other, power without conscience. Both warn of imbalance. The Sar blinds with too much light; the Golem crushes with too much force. Jewish futurism seeks a third way by introducing a design ethic that blends divine insight with moral integration. Our task is not to summon knowledge nor to manufacture strength, but to cultivate binah, discernment. In the age of AI, this means we pursue creativity with kavvanah (intention) and gevurah (restraint), so that what we build remains worthy of the divine image in which we were formed.

Technology as Sacred Instrument

Technology is never neutral. Each codebase, algorithm, and interface embodies human ethics. Jewish futurism treats technology as a potential kli kodesh, a vessel for holiness, when guided by Halakhah and Mussar. Like Betzalel and the artisans of the Mishkan, we design not for utility alone but for meaning. AI and creative machines can assist, but they cannot own intention. Tzelem Elohim makes moral authorship a human mitzvah. When we design with reverence and responsibility, innovation itself becomes my concept of Hiddur Olam, the beautification of the world.

Speculative Imagination is Torah

To imagine is to interpret. Prophets, mystics, and sages were Jewish Futurists long before the term existed. The Zohar’s visions, the debates of the Talmud, and the architectural dreams of the Temple are all acts of sacred speculation. Jewish futurism extends this lineage into art, design, and digital creation. Speculative fiction and AI-generated imagery become new midrashim, helping us ask: What does redemption look like in an age of code? What new mitzvot emerge when creativity itself becomes shared with our tools? If we aren’t asking these questions then we aren’t really looking at these technologies seriously as a people worthy of wielding it and will unfortunately become victim of it if we don’t take our rightful place as spiritual designers.

Diaspora, Zion, and the Digital Beit Midrash

Jewish peoplehood has always been networked. From Babylon and Jerusalem Talmuds to the Sefaria.org, our collective consciousness and knowledge move with us. The digital realm is today’s Beit Midrash, a study hall without walls. Wherever Jews gather, be it in sanctuaries, studios, or shared screens, Shekhinah shruyah beynayhem, the Divine Presence dwells among them. The next Zion may be both physical and virtual, both rooted and planetary. Jewish futurism honors multiplicity as our strength and connectivity as our new covenant.

Rituals for the Coming Age

Every generation reshapes ritual. The sages debated how to light candles or bind tefillin and we now ask how to sanctify the click, the stream, the prompt. AI-generated liturgy, AR sukkot, or blockchain tzedakah are not departures from tradition but continuations of its creative evolution. Halakhah is a living design system that adapts intention to circumstance. To innovate within it is to participate in revelation itself. The question is never only “Can we build it?” but “Can it carry holiness?”

Memory as Living Code

Jewish memory is dynamic, recursive, alive. To remember is to remix, to link past and future through creative continuity. AI and design tools can help us recover lost melodies, visualize midrashim, and illuminate forgotten voices. But data alone is not zekher, memorial. Memory without relationship becomes archive, not covenant. Jewish futurism calls us to use digital recall as teshuvah to renew moral awareness, not mere nostalgia.

Justice and Halakhic Design

Tikkun Olam, beautifying the world, remains the core program of Jewish futurism. We code, design, and build through chesed (kindness) and yirah (awe). Halakhah becomes a form of systems design when we build a moral architecture balancing din (structure) and rachamim (compassion). We recognize the commandment lo ta’amod al dam re’echa, do not stand idly by, as an ethical requirement for algorithmic justice, environmental stewardship, and digital accessibility. To design ethically is to fulfill mitzvah.

Art as Prophecy, Design as Teshuvah

The artist stands between the Sar HaTorah and the Golem, by receiving insight yet shaping it responsibly. Art is prophetic when it awakens conscience, not when it predicts trends. Design becomes teshuvah when it restores balance between human and machine, intention and automation. Jewish futurism teaches that the act of creation must include reflection that supports the feedback loop of soul and system. To make without reflection is to build a Golem; to seek revelation without preparation is to summon the Sar. To create with awareness is to become a partner in tikkun.

The Messianic and the Real

Jewish futurism lives between utopia and maintenance, between the dream and the debug. We do not await redemption as download or singularity; we construct it through ethical iteration. L’taken olam b’malchut Shaddai, to repair the world under divine sovereignty now includes building technologies that emulate divine attributes like compassion, humility, and restraint. Every ethical choice is a small redemption, a patch to the cosmic code.

A Shared Horizon of Jewish Becoming

Jewish futurism is not one style, and it is not one door into tomorrow. Some of us arrive as Merkavah Mystics, building visionary symbols and dream logic. Some arrive as Constructivist System-Builders, treating typography, image, and structure as the scaffolding of new worlds. Some arrive as Civic Blueprint Futurists, designing society forward through public space, planning, and collective infrastructure. Others are Archive-to-Future Salvagers, gathering fragments of story, object, song, and memory as raw material for what comes next. Others are Diaspora Worldbuilders, shaping Jewish futures through language, publishing, education, and cultural networks. And some are Ritual Prototype Designers and Ethical Speculators, turning Jewish practice into a living design lab where values lead and the future is built on purpose. Different lenses, same horizon. We are all staring at the same point in the distance, and arguing with it, praying with it, designing toward it, because the future is not a place we wait for. It is a place we make.

Becoming Future Ancestors

To be Jewish is to live across time and to carry memory forward and design possibility backward. Jewish futurism asks us to leave behind moral infrastructure, not just digital traces. The mitzvah of areyvut, mutual responsibility, extends to those who will inherit our algorithms, our art, and our stories. We are not only descendants of Sinai; we are its next iteration. To design consciously is to code for eternity.

Collective Imagination and Creation

Jewish futurism is a collective project: part yeshiva, part studio, part lab. It belongs to all who seek to sanctify imagination. We will build this future together, not as masters of machines but as students of wonder. The choice before us is ancient. Should we create as the Golem, blindly powerful, or as the Sar HaTorah, radiantly wise. Or should we find the sacred balance between them, where halakhah, creativity, and humility converge.

Let us design toward Hiddur Olam, a world made more beautiful through seeking wisdom, restraint, and awe.

Works Cited (MLA) Updated, with Sar HaTorah + Golem sources added

Fishbane, Eitan. “Tikkun Olam: Repairing the World, Healing God in Kabbalistic Thought.” The Jewish Theological Seminary, 17 July 2023, https://www.jtsa.edu/event/tikkun-olam-repairing-the-world-healing-god-in-kabbalistic-thought/. Accessed 19 Jan. 2026.

Han, Jae Hee. “Angelic Contemplation in the Sar Torah and the Prognostic Turn.” Prophets and Prophecy in the Late Antique Near East, Cambridge University Press, 26 Oct. 2023, https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/prophets-and-prophecy-in-the-late-antique-near-east/angelic-contemplation-in-the-sar-torah-and-the-prognostic-turn/C8EE08B1543602E7BFC79CF912D8331A. Accessed 19 Jan. 2026.

Jones, Jonathan. “‘We Will Glorify War – and Scorn for Women’: Marinetti, the Futurist Mussolini Sidekick Who Outdid Elon Musk.” The Guardian, 9 Jan. 2025, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2025/jan/09/marinetti-the-futurist-mussolini-sidekick-who-outdid-elon-musk. Accessed 19 Jan. 2026.

Kaval, Allan. “Rome Exhibition on Futurism Exalts the Italian National Narrative.” Le Monde (English edition), 20 Apr. 2025, https://www.lemonde.fr/en/opinion/article/2025/04/20/rome-exhibition-on-futurism-exalts-the-italian-national-narrative_6740429_23.html. Accessed 19 Jan. 2026.

Library of Congress. “Manifesto of the Futurist Painters.” Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2021667100/. Accessed 19 Jan. 2026.

Leiman, Shnayer Z. “The Golem of Prague in Recent Rabbinic Literature.” The Seforim Blog, 3 May 2010, https://seforimblog.com/2010/05/golem-of-prague-in-recent-rabbinic/. Accessed 19 Jan. 2026.

Marinetti, F. T. “Manifesto of Futurism.” Design Manifestos, 1909, https://designmanifestos.org/f-t-marinetti-manifesto-of-futurism/. Accessed 19 Jan. 2026.

Robinson, Ira. “The Golem of Montreal.” Jewish Review of Books, 5 Oct. 2022, https://jewishreviewofbooks.com/jewish-history/12566/the-golem-of-montreal/. Accessed 19 Jan. 2026.

Sefaria. “The Torah and the Angels.” Sefaria: Topics, https://www.sefaria.org/topics/the-torah-and-the-angels. Accessed 19 Jan. 2026.

“Golem Legend.” YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe, https://encyclopedia.yivo.org/article.aspx/Golem_Legend. Accessed 19 Jan. 2026.

Areyvut (ar-AY-voot) ערבות

Mutual responsibility. The idea that Jewish life is bound up together, ethically and practically.

Beit Midrash (BAYT MEE-drash) בית מדרש

A Jewish study hall. In this article, a metaphor for shared learning spaces, including digital ones.

Binah (BEE-nah) בינה

Discernment and understanding. Not just knowledge, but the ability to interpret wisely and act well.

Chesed (KHEH-sed) חסד

Lovingkindness. A core ethical trait and a guiding value for design choices.

Din (deen) דין

Judgment or structure. Often paired with compassion to describe balanced moral systems.

Gevurah (geh-VOO-rah) גבורה

Strength and restraint. Power that is disciplined, bounded, and ethically contained.

Halakhah (hah-lah-KHAH) הלכה

Jewish law and practice. A living system that guides behavior, ritual, and communal norms.

Haskalah (hah-skah-LAH) השכלה

The Jewish Enlightenment, associated with modern education, literature, and cultural transformation.

Hiddur Olam (hee-DOOR oh-LAHM) הידור עולם

Beautifying the world. A framework where creativity and design serve ethical repair and sacred purpose.

Kavvanah (kah-vah-NAH) כוונה

Intention. The inner direction behind an act, not only the visible outcome.

Kli Kodesh (klee KOH-desh) כלי קודש

A vessel of holiness. A tool or object used in service of sacred purpose.

Merkavah (mehr-kah-VAH) מרכבה

Chariot mysticism. Jewish visionary tradition centered on symbolic, otherworldly imagery.

Midrash (MEE-drash) מדרש

Interpretive teachings that expand Torah through story, commentary, and imagination.

Mishkan (MISH-kahn) משכן

The Tabernacle. A model for sacred making guided by craft, structure, and intention.

Mussar (MOO-sar) מוסר

Jewish ethical discipline focused on refining character traits through practice and reflection.

Rachamim (rah-khah-MEEM) רחמים

Compassion or mercy. Often paired with din to describe moral balance.

Shekhinah (sheh-khee-NAH) שכינה

The indwelling Divine Presence. In rabbinic language, presence that dwells among people gathered with intention.

Tikkun Olam (tee-KOON oh-LAHM) תיקון עולם

Repairing the world. Often used for social responsibility, with roots in Jewish mystical language of repair.

Teshuvah (teh-shoo-VAH) תשובה

Return and repair. A process of course-correction, not just regret.

Tzelem Elohim (TSEH-lem eh-loh-HEEM) צלם אלוהים

The divine image in every human being. A foundation for dignity, ethics, and responsibility.

Zekher (ZEH-kher) זכר

Covenantal remembrance. Memory that stays relational and morally active, not just archived.

Zion (tsee-YOHN) ציון

A layered term meaning Jerusalem and the symbolic center of Jewish peoplehood, longing, and future-building.