Vitebsk, a small, mostly Jewish city in the old Pale of Settlement, is remembered in the art books as a birthplace of the Russian avant‑garde, but almost never as a place where Jews were actively prototyping their own futures (Vitebsk; “In the Beginning”). In the years 1918 to 1922, if you set Vitebsk next to the qualities that define Jewish Futurism in my own framework (tradition as engine, explicit future‑orientation, speculative design, tech–spirit entanglement, liberation, and collective imagination), it starts to look less like a side chapter of Russian modernism and more like an early Jewish futurist lab. What follows is that story, told through those lenses.

Jewish futurism as a lens

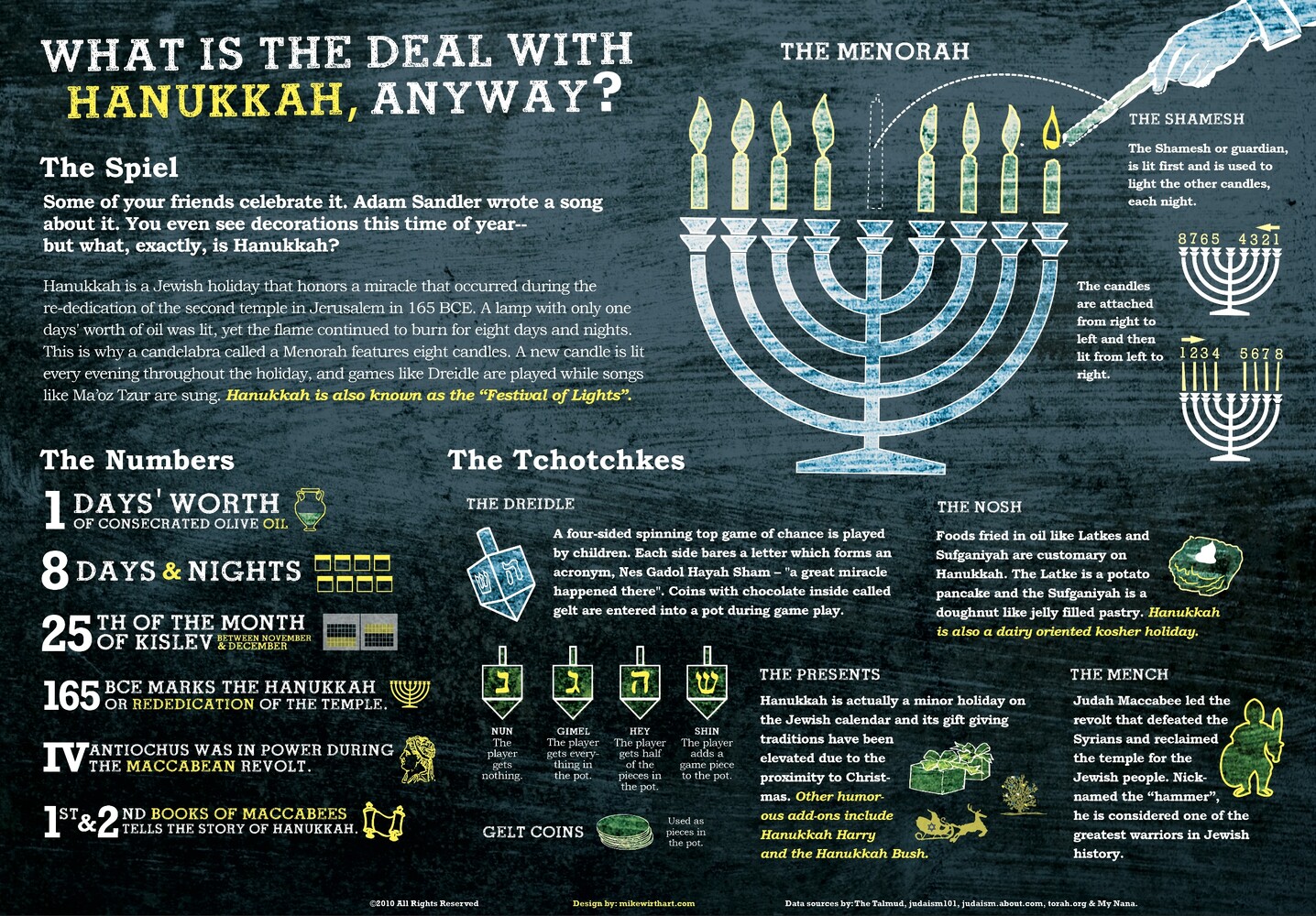

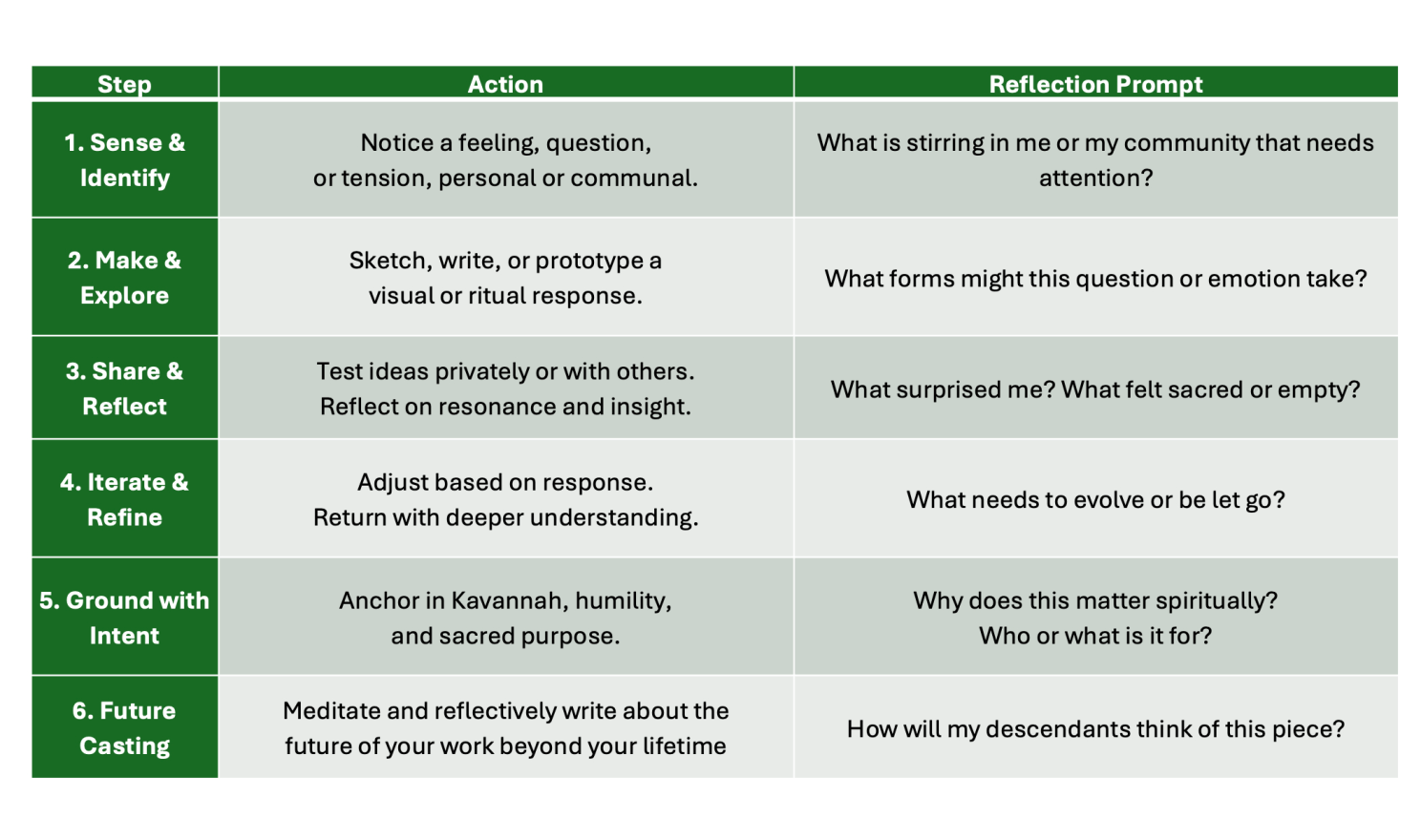

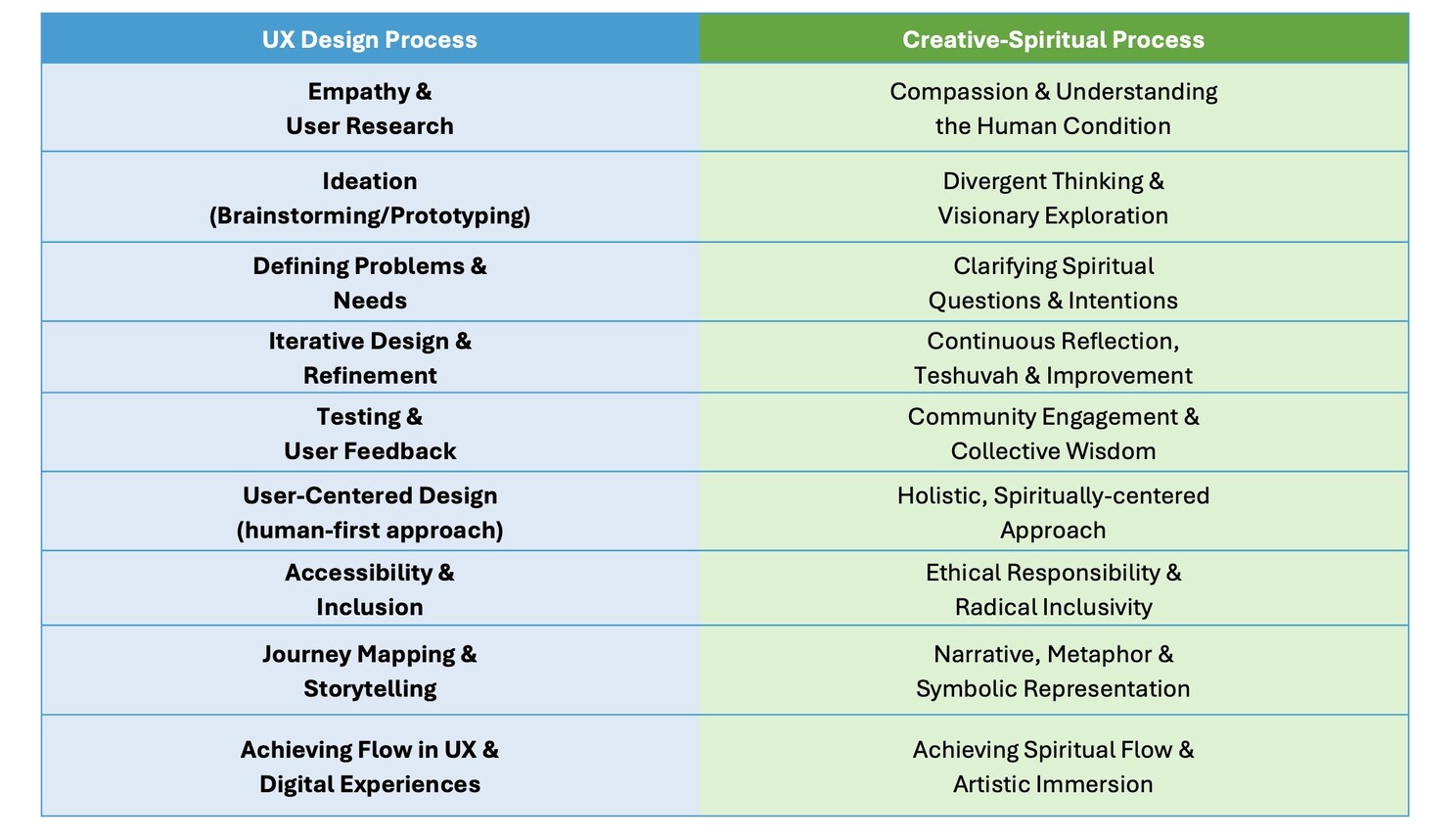

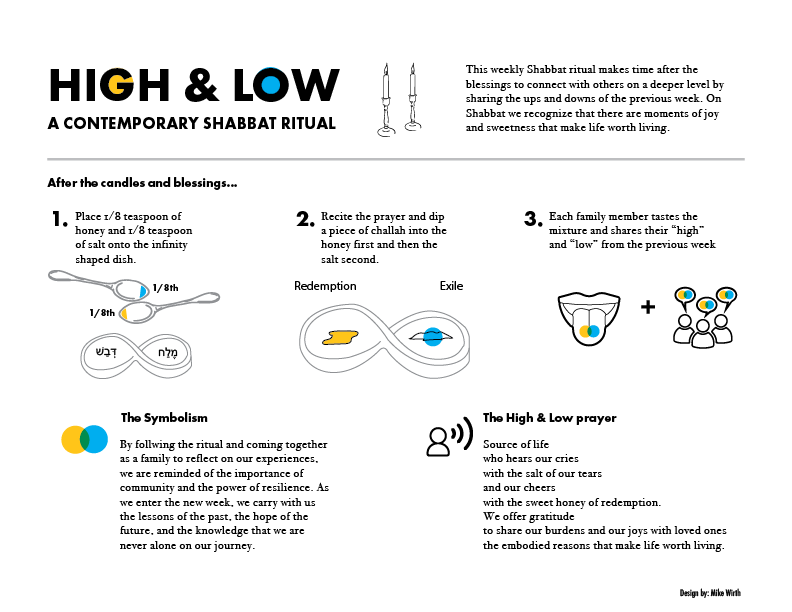

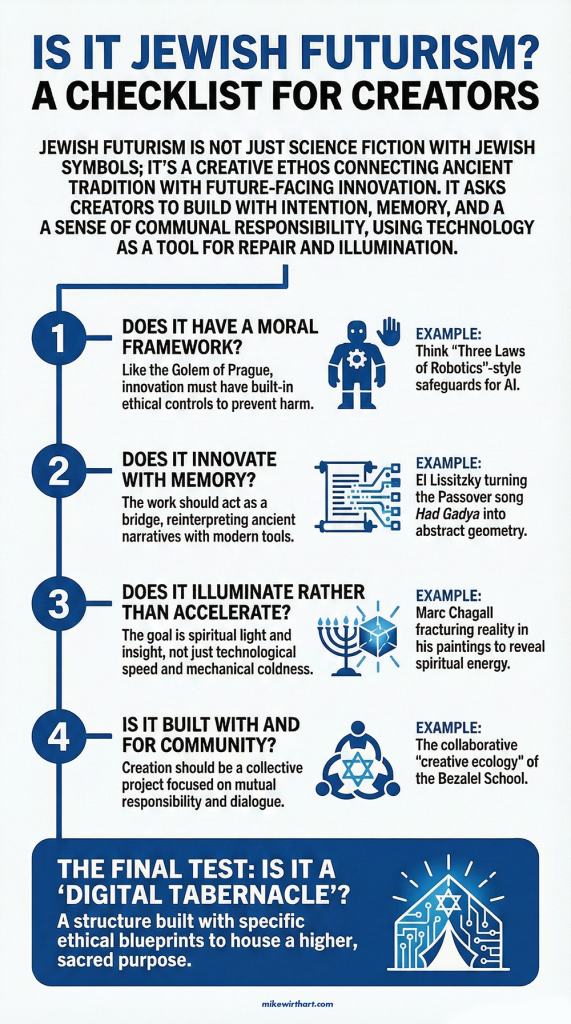

In my own writing, Jewish Futurism is a creative framework that blends design, spirituality, and technology to reimagine the future of Jewish identity, ritual, and ethics. It treats Jewish sources and symbols as engines for new worlds, leans into speculation and prototyping, and loves that “ancient in the present” feeling, where neon‑lit interfaces sit next to kabbalistic cosmology and golem legends.

If you strip that down to core moves, you get: start with Jewish values and stories, ask “what if” questions about the future, use speculative design and prototypes instead of just commentary, entangle tech and spirit, and keep liberation and repair as the moral north star. That is the checklist I am quietly running in the background as I look at Vitebsk.

The political weather

The Vitebsk experiment sits right in the storm of the Russian Civil War. The Bolsheviks had just seized power and dissolved the Constituent Assembly; Red, White, and nationalist forces were fighting across the old empire, and by 1918–1921 the war had wrecked the economy and militarized everyday life, especially in borderlands like Belarus and Ukraine (“Russian Civil War”). The new regime promised a rational, classless future, but enforced it with emergency repression and the Cheka, the Soviet secret police (“Russian Civil War”).

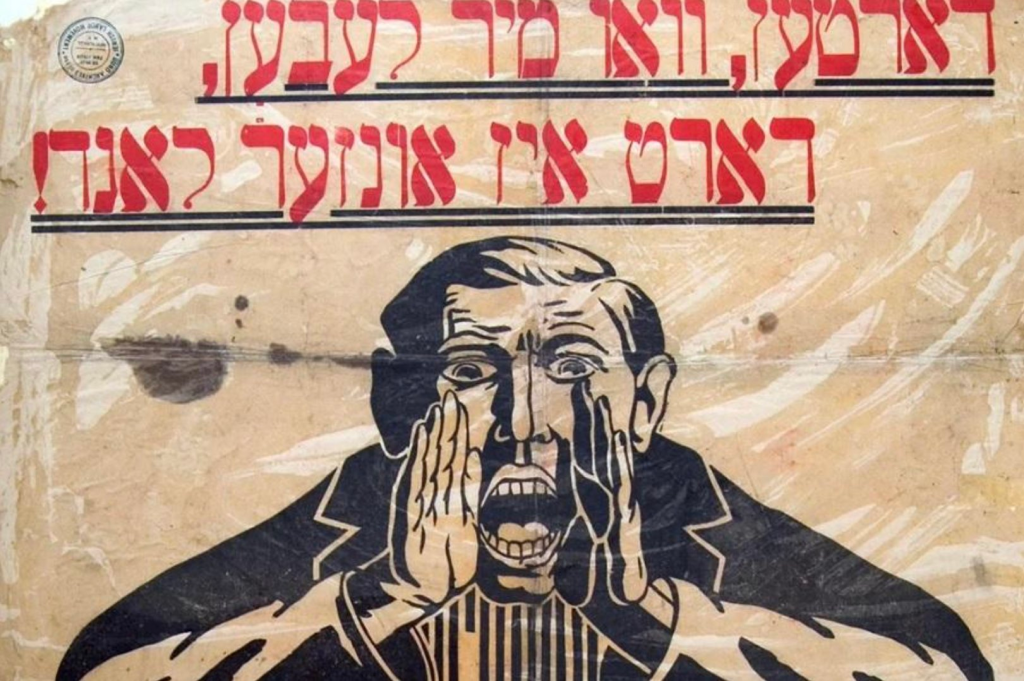

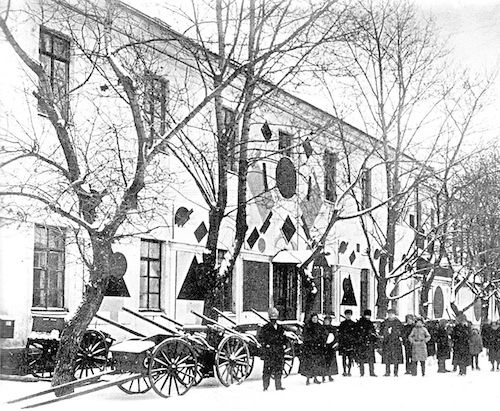

In culture, that meant art was not neutral. Festivals, agit‑prop posters, and street decorations became tools for staging the future socialist society in public space (“Russian Civil War”). In contemporary language, the state was demanding “design, not just description”: artists were expected to prototype the look and feel of a new world, not only paint it from the sidelines. Vitebsk’s People’s Art School and the UNOVIS collective were very much inside that program (“Chagall, Lissitzky, Malevich”; “UNOVIS”).

Jewish life between emancipation and trauma

For Jews, the ground had just shifted. The revolutions abolished the Pale of Settlement and the old quota regime, so on paper Jews could live, study, and work without the old legal shackles (“Pale of Settlement”). Cities in the former Pale, including Vitebsk, suddenly opened up Jewish participation in schools, professions, soviets, and new cultural institutions (Vitebsk).

At the same time, the civil war unleashed catastrophic pogroms. In nearby Ukraine and parts of Belarus, White armies, nationalist militias, and irregular bands killed tens of thousands of Jews and displaced many more; refugees and bad news moved through the region constantly (“Pogroms during the Russian Civil War”). Early Soviet nationality policy recognized Jews as a “nationality” and created Jewish sections of the Party (Evsektsiia), pushing Jews into the socialist project while attacking synagogues, Hebrew, and traditional institutions, even as secular Yiddish culture and left‑wing Jewish politics boomed (Vitebsk).

In other words, Jews in and around Vitebsk were newly emancipated on paper, traumatized and precarious in practice, and under pressure to imagine “what happens to Jewishness next”.

Vitebsk as a Jewish, experimental city

Before the revolution, Vitebsk was a major Jewish center, with synagogues, heders, Yiddish markets, and a thick stew of Zionist, Bundist, and other Jewish politics (Vitebsk; “In the Beginning”). After 1917, Soviet institutions sat right on top of that fabric: workers’ councils, clubs, and schools tried to re‑engineer daily life (“In the Beginning”).

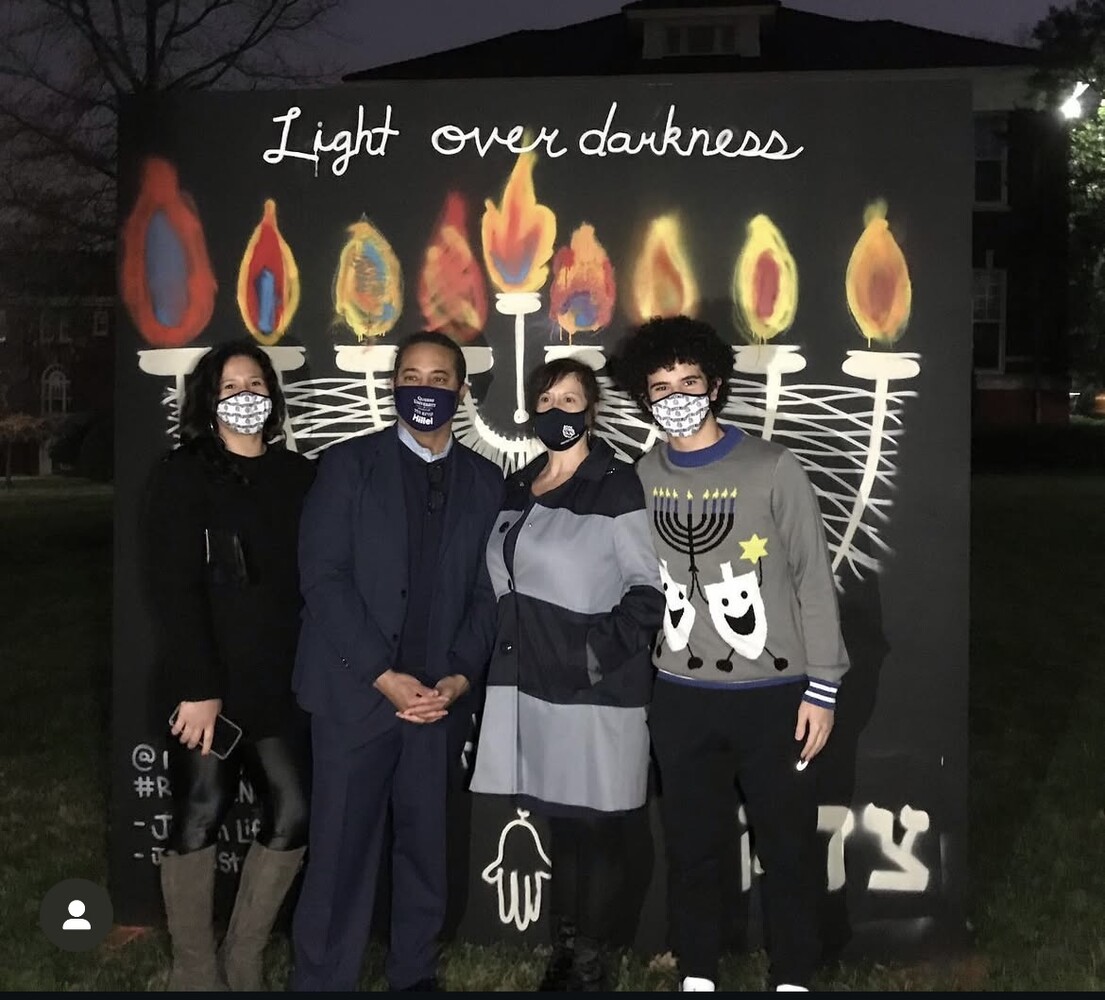

In 1918, Marc Chagall came home from Petrograd and founded the People’s Art School, a free modern art school for local working‑class youth who had been locked out of Imperial academies, many of them Jewish (“Chagall, Lissitzky, Malevich”). He recruited avant‑garde teachers, turned Vitebsk into a small node in the international modernist network, and handed real tools and training to kids whose families had been under Tsarist restrictions only a few years earlier (“Chagall, Lissitzky, Malevich”). That is very close to what I mean today by a Jewish futurist “lab”: a place where a specific Jewish community uses design and education to build its own cultural future (Wirth).

Chagall’s speculative shtetl

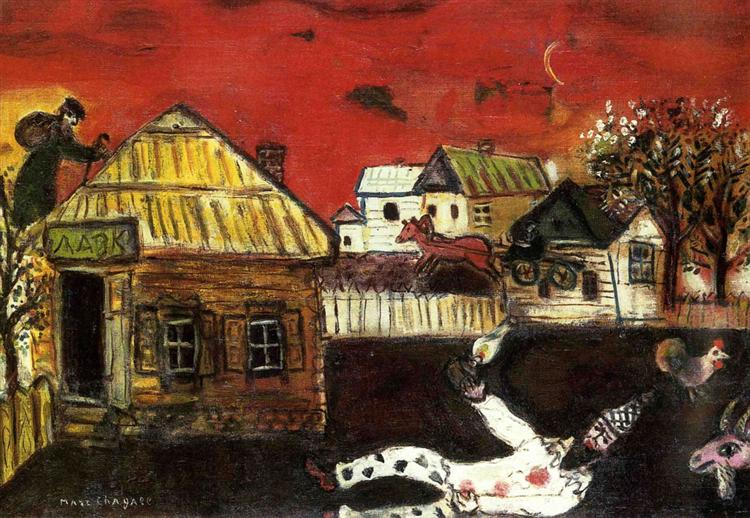

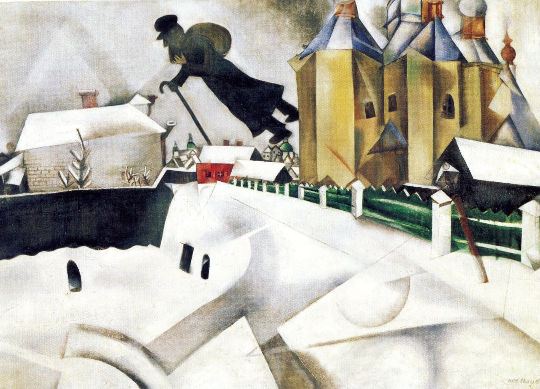

In those Vitebsk years, Chagall painted the works everyone now knows: flying couples and goats, skewed rooftops, synagogues hovering over town, a fiddler straddling chimneys. These are not just nostalgic postcards of the shtetl; they warp gravity and time. Past, present, and some maybe‑world bleed into each other.

From a Jewish futurism angle, Chagall is doing exactly what I try to do with neon interfaces and AI‑inflected ritual objects. He is starting with Jewish stories and symbols and then using them as engines to invent new visual physics. The familiar becomes strange without losing its soul. That “ancient in the present” feeling that I care about so much is already there in his sky‑bound Vitebsk. His paintings read like prototypes of Jewish life under different rules, which is one of the key tests I use today for whether something is really operating as Jewish futurism.

UNOVIS in the streets: the classic proto–Jewish futurist moment

The moment that feels most like a straight‑up Jewish futurist intervention is when UNOVIS took the streets. Around 1919–1920, the collective of teachers and students around Malevich designed Suprematist banners, painted trams and building facades, and marched in revolutionary festivals with Black Squares and other abstract emblems.

This is happening in a mostly Jewish city. The same streets that carried Jews to synagogue and market are suddenly wrapped in a new visual operating system. Instead of only Stars of David and Hebrew letters, there are squares, circles, and crosses floating over shopfronts and tram cars. The Black Square, which Malevich had already framed like a kind of icon, becomes a civic ritual sign on flags and sleeves.

If I treat this like any other futurist project, it is textbook: a collective of young artists, many Jewish, redesigns the visual and ritual grammar of their own city, at scale, as a way of sketching a possible future world. It is design, not description. It is explicitly future‑oriented, embedded in a particular Jewish place, and it lives at the intersection of politics, symbol, and street‑level experience. Those are all the boxes I check in my Jewish Futurist design process today.

Lissitzky: from Had Gadya to pangeometry

El Lissitzky is the other key bridge figure for me. Before and during his Vitebsk period, he designed Hebrew and Yiddish books, including a famous Had Gadya, where the Aramaic Passover song gets re‑composed with bold letters and geometric forms. Scholars like Igor Dukhan describe this as a move from “Jewish style” into a universal “pangeometry,” but they note that the universalism is built right on top of Jewish source material.

In my terms, that is pure tradition‑as‑engine. He is not sprinkling Hebrew as flavor; the text itself is the design brief for a new visual system. In Vitebsk, Lissitzky then develops PROUN, a body of hybrid painting‑architecture pieces that look like floating structures in non‑Euclidean space, which he framed as “stations” between painting and architecture for a future society.

That move—from a Passover song to speculative spatial diagrams for a different world—is the same arc I trace when I talk about going from Torah into high‑tech ritual objects. It is also a strong example of what I call entangling technology and spirituality: using the tools of print, geometry, and architectural thinking to work through spiritual questions about where and how a Jewish (and human) body might live in a new order.

Malevich, UNOVIS, and secular ritual systems

Malevich arrives in Vitebsk in 1919, invited by Lissitzky, and soon becomes the center of gravity at the People’s Art School. His experience with Cubo-Futurism ignites a shift in painting in the town. With him, teachers and students form UNOVIS, sign work collectively, and treat Suprematism as a total worldview. He talks about the Black Square as an “icon” and about non‑objectivity as a new metaphysics of pure feeling.

In a Jewish environment, that lands differently than it would in a neutral setting. This is a town used to Torah scrolls, midrash, and messianic talk. UNOVIS is effectively rolling out a secular ritual system on top of that: new symbols, new processions, new “liturgies” of banners and posters that promise a transformed world. It is not Jewish ritual, but it is a speculative ritual layer in Jewish space, and Jewish students are the ones building it.

Viewed with my framework, that is another type of tech–spirit entanglement: using visual technology and collective performance to test out a different metaphysics in the same streets where older Jewish ones still echo. It shows how close the Jewish Futurist line of questioning is to the avant‑garde’s own messianic streak, even when the language is strictly secular.

Two Jewish futures in one school

Inside the People’s Art School, there is a clear tension between two ways of thinking about the future. Chagall holds onto figures, stories, synagogues, and shtetl scenes, but floats them, tilts them, and sets them in saturated color. In my terms, he is modeling continuity through creative distortion: Jewish narrative and ritual feeling that survive and adapt without disappearing.

Malevich, and the UNOVIS path, offer a different horizon: strip away all representation and identity markers and escape into pure geometric universals that are supposed to belong to everyone. Many students follow that road. Chagall finds himself sidelined and eventually leaves Vitebsk in 1920.

From a Jewish Futurist vantage point, this is not only a stylistic argument. It is a fight over how you imagine a Jewish future under pressure. One path keeps tradition as engine and accepts that Jewishness will show in the work. The other tries to leap into something like a post‑Jewish universalism, betting that liberation means dissolving markers altogether. That same tension is alive now, whenever Jewish futurist work decides how visible to make its Jewish sources and audiences.

Right- Marc Chagall, Anywhere out of the World, 1915–19. Oil on cardboard mounted on canvas.

Why no one called it “Jewish futurism”

Curators and critics have done a lot of work on Vitebsk. The Jewish Museum show “Chagall, Lissitzky, Malevich: The Russian Avant‑Garde in Vitebsk, 1918–1922,” along with its catalogue, makes it clear the town was heavily Jewish and that Chagall and Lissitzky’s Jewish identities matter. Reviews in Studio International, the New York Times, Artmargins, Tablet, and Jewish Currents all talk about Vitebsk as a utopian laboratory.

What they do not do is connect that story to the language and methods that Jewish futurism uses now. The town is filed under “Russian avant‑garde,” while Jewish futurism is usually reserved for contemporary art, speculative fiction, and design work. The result is a blind spot: a historical moment that already behaves like a Jewish futurist lab is sitting in one file folder, and the present movement that could really use that precedent is sitting in another.

Vitebsk as an early Jewish Futurist lab

If I run Vitebsk through my own Jewish futurist checklist, it lights up. Tradition as engine: Chagall’s speculative shtetl and Lissitzky’s Had Gadya redraw Jewish stories and symbols into new visual systems. Explicit future‑orientation: a Jewish population just freed from the Pale and brutalized by pogroms is forced to imagine new futures in real time. Design, not just description: the People’s Art School, PROUN, and UNOVIS’s trams and banners are prototypes of new civic and spiritual grammars, not commentary about the old one.

Tech and media entangled with spirituality: abstract signs, print, and architecture take on ritual roles in a Jewish city. Liberation and repair as north stars: even when the rhetoric is Marxist, the underlying drive is to get out from under Tsarist antisemitism and civil‑war terror and build something more just. Collective, situated imagination: a specific community, in a specific town, turns its own streets, schools, and bodies into a laboratory for what Jewish and human life might become next.

Seen that way, Vitebsk is not an odd, provincial side note to Russian modernism. It is an early node in the same line of Jewish making that runs through my own neon‑lit spiritual objects, AI‑inflected Torah experiments, and design‑driven rituals today. Naming it as such is not just about correcting a footnote in art history. It is a way of claiming ancestors for Jewish futurism and remembering that this mode of thinking has been with us, in one form or another, since at least the moment a few Jewish kids in Vitebsk painted Suprematist banners for a world they had not yet learned how to live in.

Core Works Cited

“Chagall, Lissitzky, Malevich: The Russian Avant-Garde in Vitebsk, 1918–1922.” The Jewish Museum, www.thejewishmuseum.org/exhibitions/chagall-lissitzky-malevich-the-russian-avant-garde-in-vitebsk-1918-1922.[1]

Dukhan, Igor. “El Lissitzky – Jewish as Universal: From Jewish Style to Pangeometry.” Monoskop, monoskop.org/images/6/6e/Dukhan_Igor_2007_El_Lissitzky_Jewish_as_Universal_From_Jewish_Style_to_Pangeometry.pdf.

“In the Beginning, There Was Vitebsk.” The Forward, 12 Mar. 2008, forward.com/culture/12913/in-the-beginning-there-was-vitebsk-01455/.

Jewish Virtual Library. “Vitebsk.” Jewish Virtual Library, www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/vitebsk.[4]

“Russian Civil War.” Encyclopaedia Britannica, www.britannica.com/event/Russian-Civil-War.[5]

“Pogroms during the Russian Civil War.” Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pogroms_during_the_Russian_Civil_War.

“Suprematism, Part II: El Lissitzky.” Smarthistory, 27 Sept. 2019, smarthistory.org/suprematism-part-ii-el-lissitzky/.

“UNOVIS.” Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/UNOVIS.

Wirth, Mike. “Jewish Futurism.” Charlotte Muralist, 9 Mar. 2022, mikewirthart.com/jewish-futurism/.