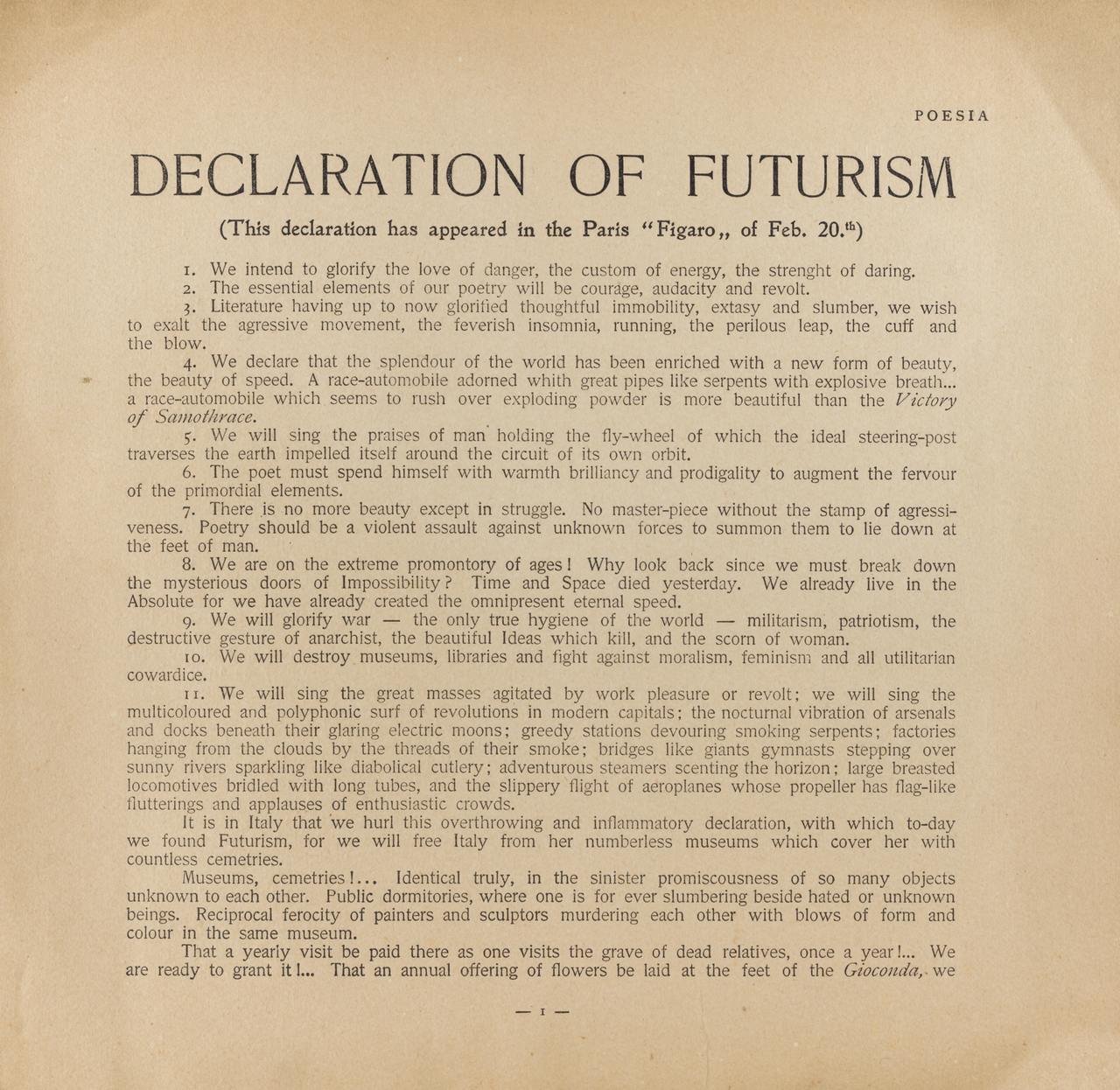

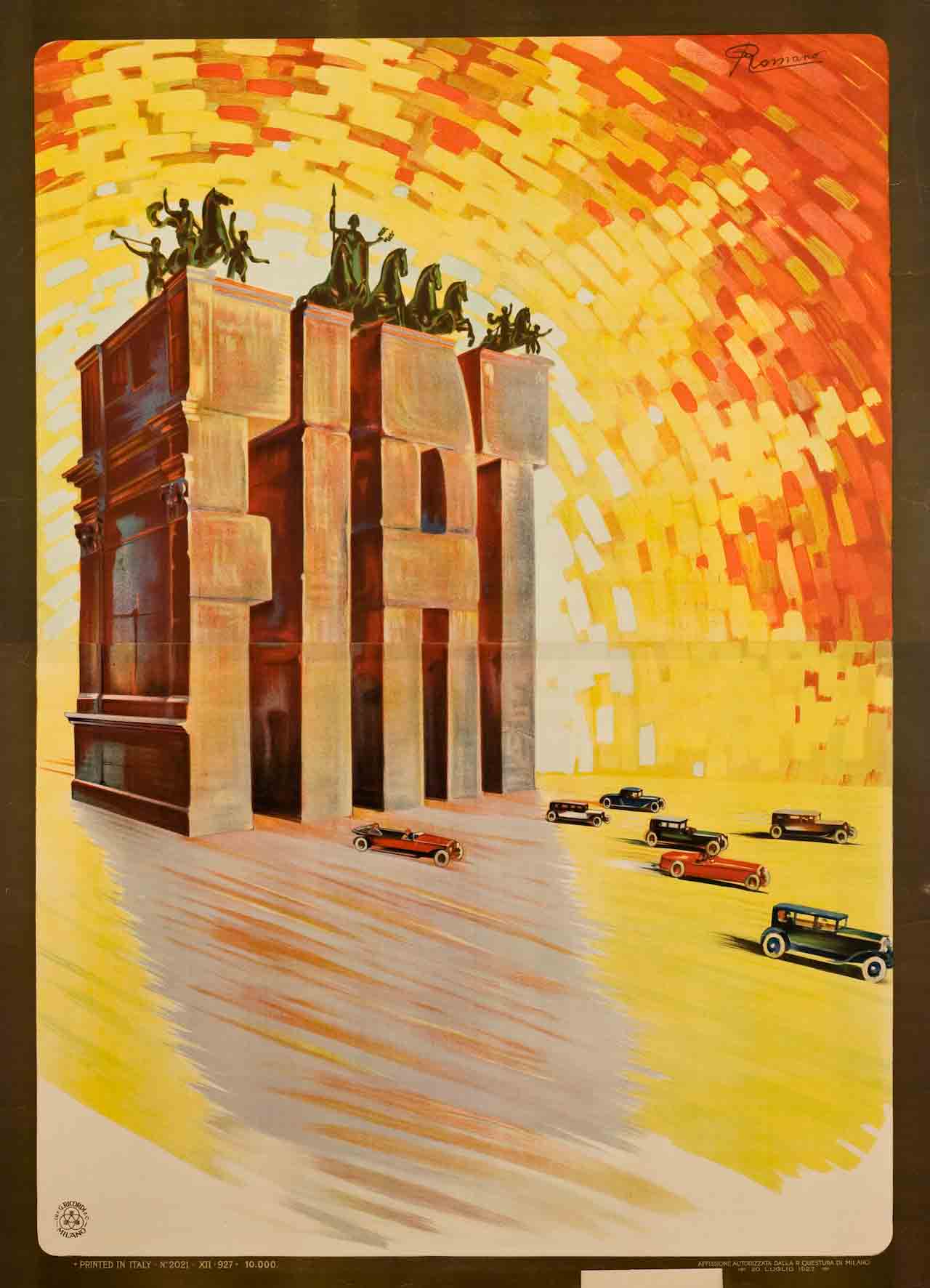

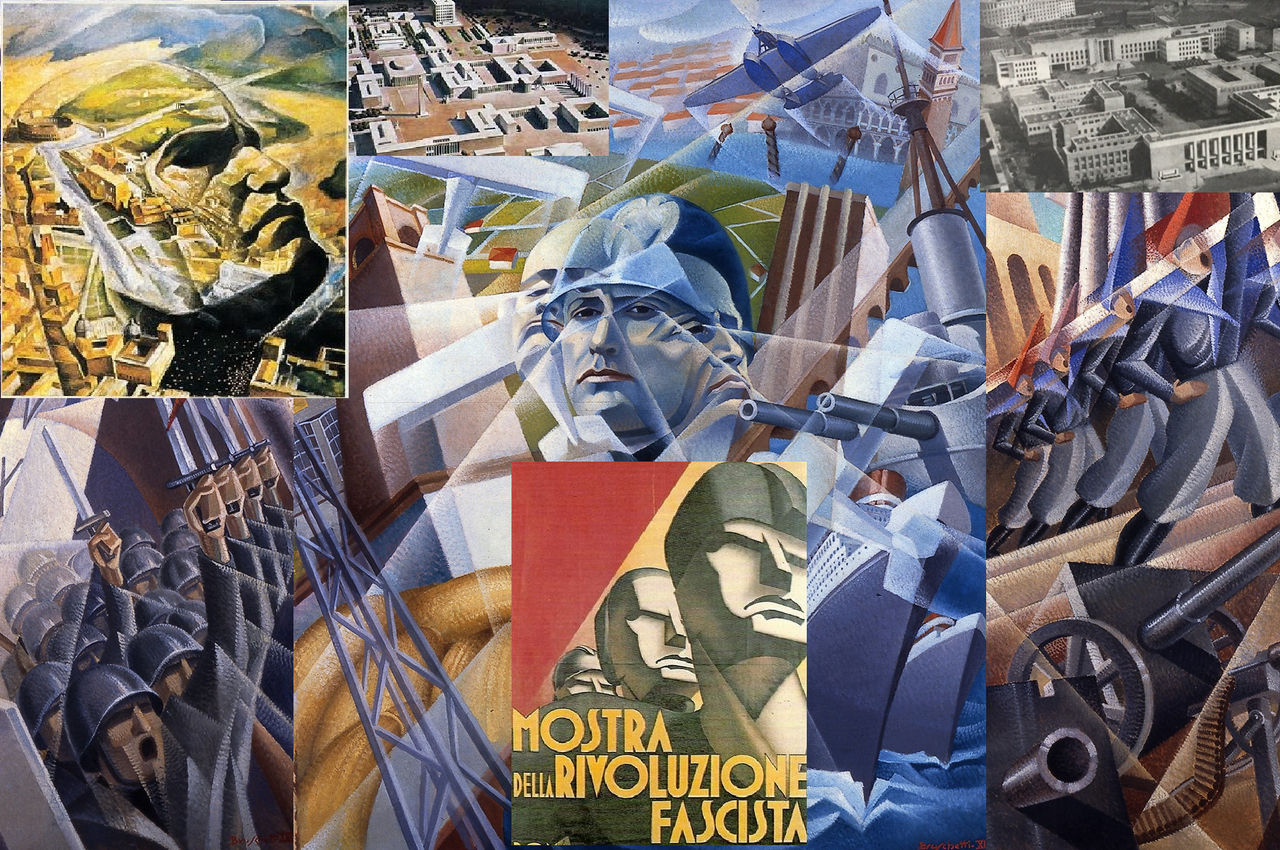

When I teach graphic design history at Queens University of Charlotte, we hit a point in the semester that always makes me a little uncomfortable, because I know it’s coming before the students do. We’re talking about Italian Futurism, those bold typographic posters, a visionary sounding manifesto bursting with energy, those declarations about speed and machines and destroying museums. At first, students lean forward and feel like the work looks alive and feels thrilling. And then we read more deeply into the Marinetti’s words and we see that this movement became a propaganda apparatus for Mussolini’s fascist regime.

Those promising-sounding ideas about breaking with the past? They’re loaded with fascist and racist intentions. That gorgeous energy? It was weaponized.

This is the pedagogical tightrope I walk every semester, and it’s the same tightrope I’m walking in my work on Jewish futurism.

I’m trying to rescue the core impulse of futurism, the bold, beautiful desire to imagine and design better futures, from what Italian Futurism did to it.

Because here’s the thing: Italian Futurism started with legitimate, even utopian desires, and it still became a cautionary tale. If you’re going to study any kind of futurism seriously, you need to meet Italian Futurism early, not to emulate it, but to understand exactly what can go wrong when speed replaces wisdom and aesthetics trump ethics.

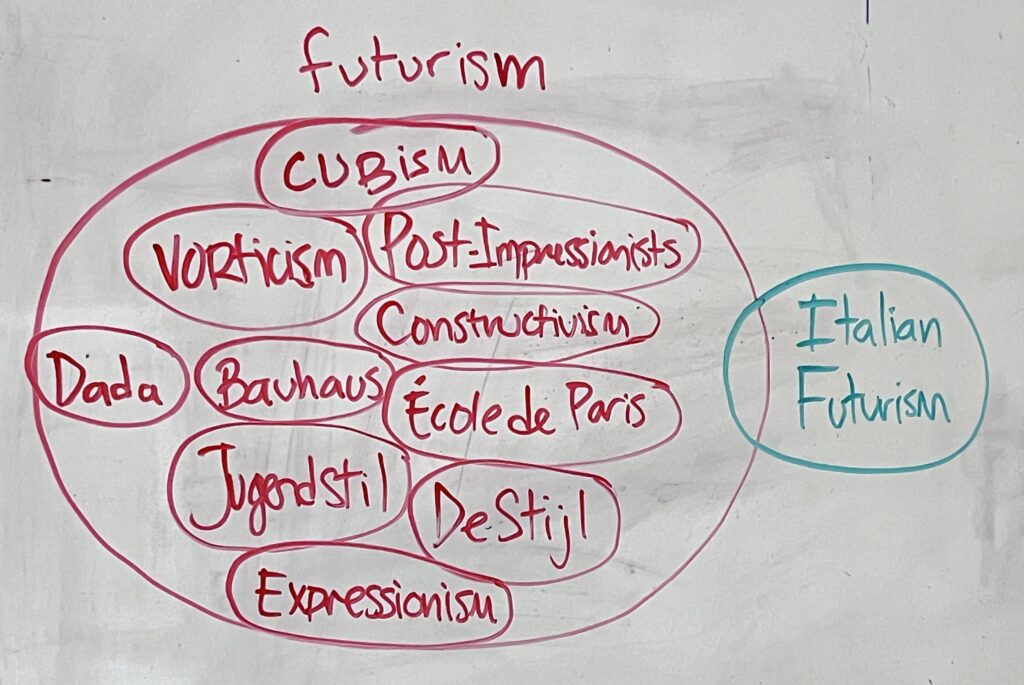

Futurism vs futurism: Why the Capital Letter Matters

I’ve started being very careful about capital F versus lowercase f. Futurism with a capital F names a specific historical movement: Marinetti’s Italian avant-garde, with all its inherited baggage. It’s bound up with nationalism, misogyny, the glorification of war as “the world’s only hygiene,” and an eventual merger with Mussolini’s Fascist Party in 1920. When I write “Futurism,” I’m signaling: we’re talking about that movement, that history, those consequences.

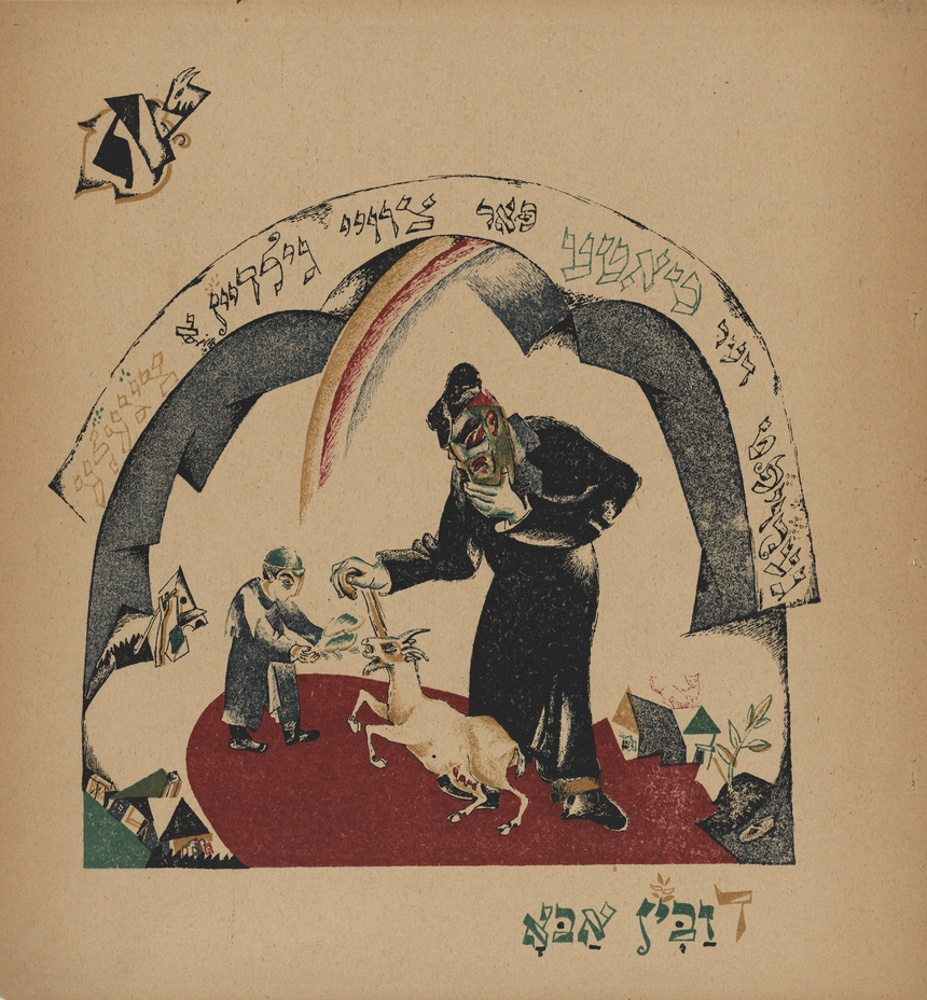

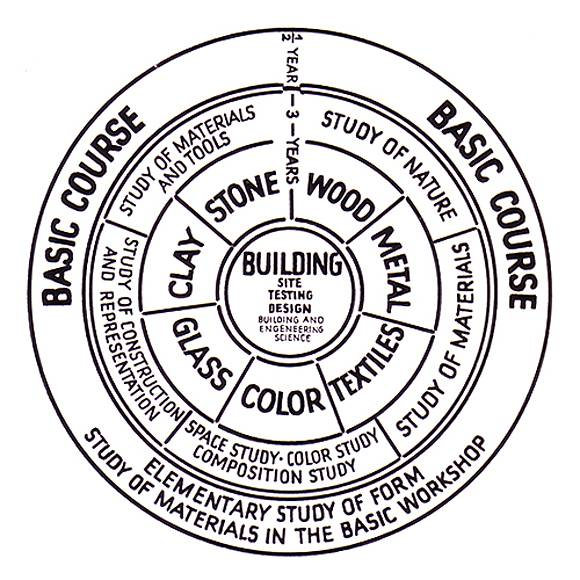

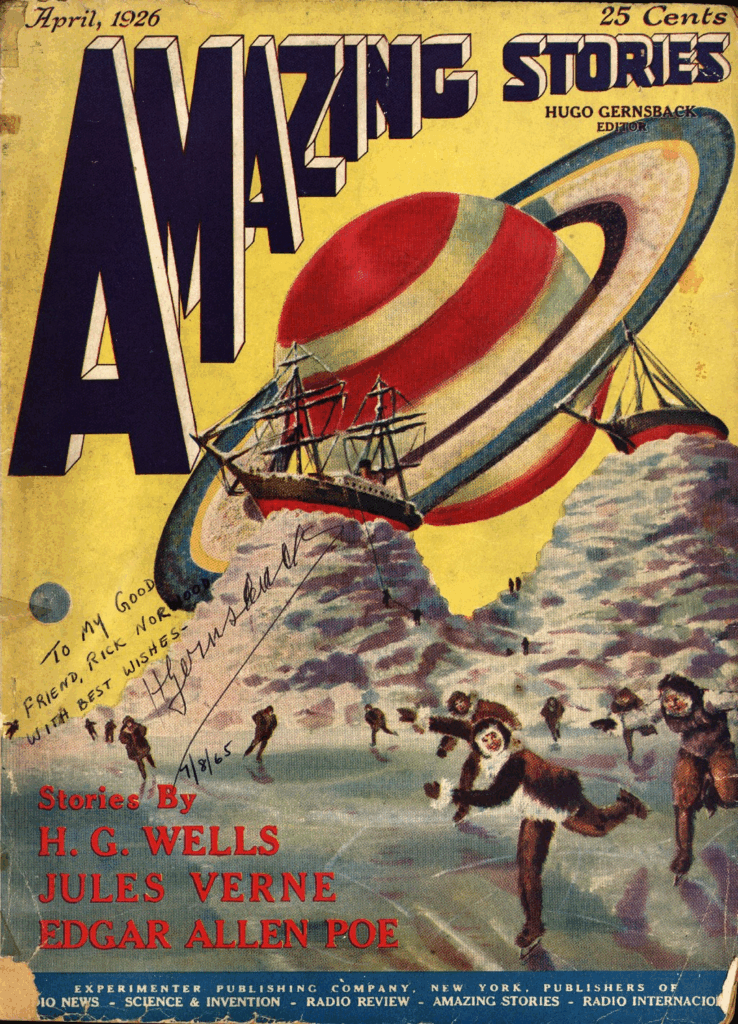

Futurism with a lowercase “f” names something broader and more perennial: the human impulse to imagine, prototype, and design what comes next. It’s the practice of speculating about futures, whether through art, spirituality, technology, or politics. Lowercase futurism is a method and a desire, not an ideology. It’s the thing Jewish futurism, Afrofuturism, Queerfuturism, Sinofuturism, and Gulf futurism all share: the courage to ask what could be, and the willingness to build toward it.

This distinction isn’t just academic. It gives us critical vocabulary. Capital-F Futurism becomes an object of analysis and caution, the ancestor we study to avoid repeating. Lowercase futurism becomes a space for repair, reinvention, and new ethical commitments. Jewish futurism inherits the impulse without inheriting the violence.

How Futurist Movements Emerge: What They All Want at First

Futurist movements consistently arise during periods of dramatic technological transformation and cultural rupture. Italian Futurism emerged from a very specific crisis. Turn-of-the-century Italy was struggling in ways that made the country feel stuck in the past. The government was weak and unstable. There was no real national identity binding the regions together. Industrial development lagged decades behind other European powers. Poverty was widespread, modernization faced fierce resistance, crime and corruption were endemic, and millions of Italians were emigrating in search of better lives.

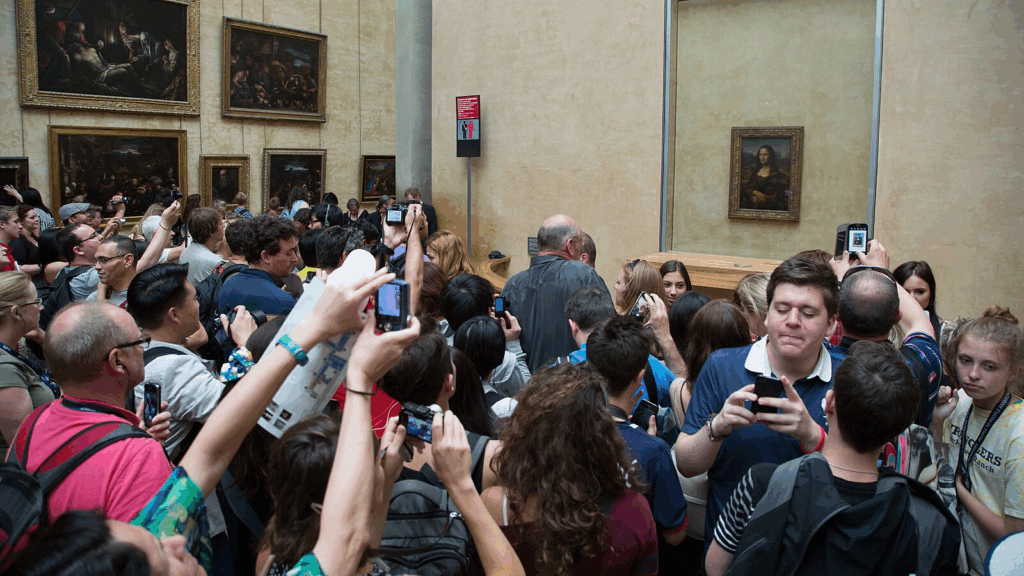

Meanwhile, foreign tourists flooded Italy to gaze at ancient ruins and Renaissance masterpieces, treating the country like a beautiful museum, a relic of what it once was. For young Italian intellectuals like Marinetti, this was humiliating. People came to see what Italy was, not what it is or could become. The weight of the past felt suffocating.

This pattern repeats across other futurist movements. Afrofuturism developed in response to the ongoing trauma of the transatlantic slave trade and systemic oppression, seeking to reclaim narratives and imagine liberation. Gulf futurism arose from the rapid, oil-driven transformation of the Arab Gulf states. Sinofuturism responds to China’s technological rise and Western anxieties about shifting global power.

Despite their different contexts, these movements share foundational patterns. They reject traditions they perceive as inadequate or stifling. They embrace technology as a catalyst for radical cultural change. Most importantly, they assert the right to imagine and define their own futures rather than accepting externally imposed visions.

Futurist movements emerge from communities experiencing rupture, whether from rapid modernization, colonialism, diaspora, or globalization. They often adopt manifesto culture, broadcasting bold visions to gather followers. They’re youth-driven, appealing to younger generations eager to break free from what they see as the constraints of older orders.

At their inception, futurist movements typically seek cultural sovereignty, the synthesis of heritage and innovation, celebration of dynamism and transformation, radical breaks from oppressive pasts, and social change through technology. These are legitimate, even beautiful desires. The critical question is: what values guide those transformative visions? Italian Futurism demonstrates what happens when the desire to destroy the past overwhelms the responsibility to build just futures.

The Promise and Peril of Italian Futurism

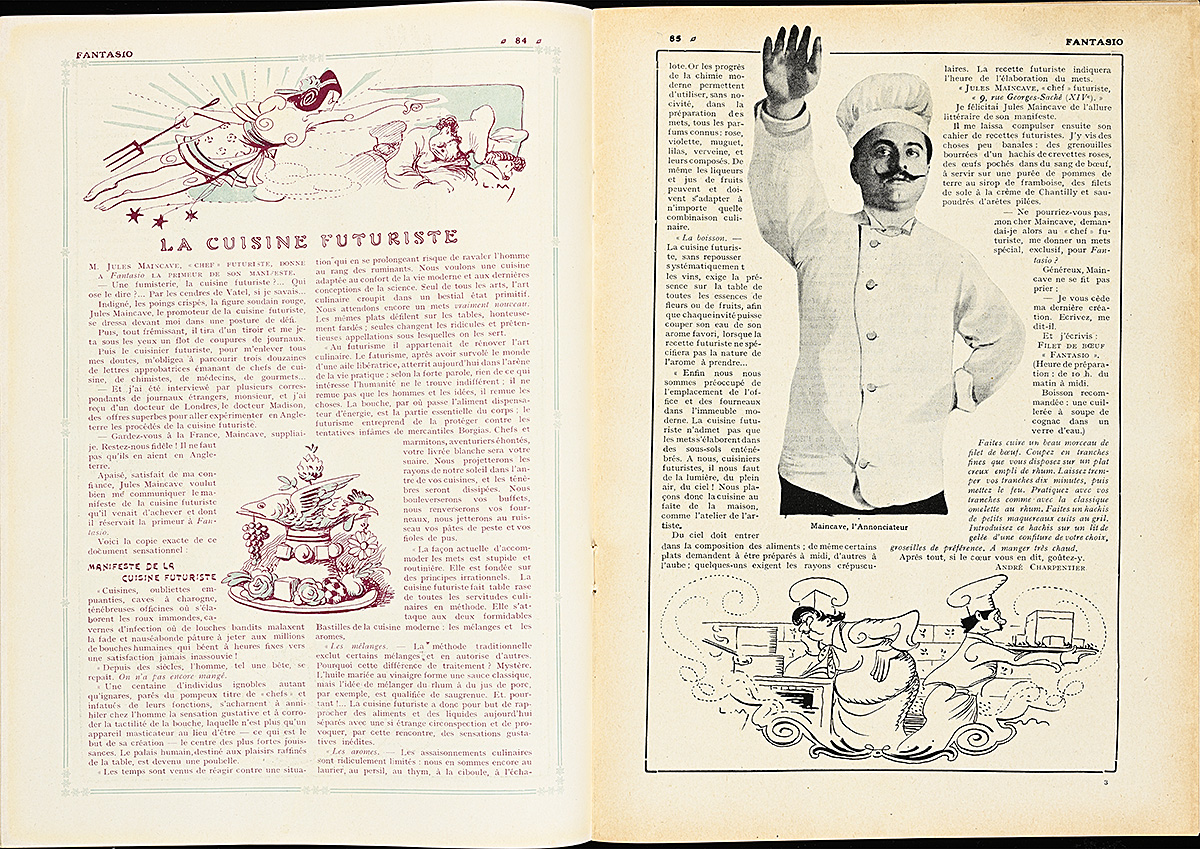

Filippo Tommaso Marinetti launched Italian Futurism with his 1909 manifesto, and it crackled with revolutionary energy. He declared the racing car more beautiful than the Winged Victory of Samothrace and announced war on museums, libraries, and academies. The movement promised total cultural transformation through speed, machines, violence, and youth.

But Marinetti wasn’t speaking metaphorically. He made actual political proposals to sell off Italy’s art heritage in bulk to other countries. Museums were “graveyards,” he argued, places that paralyzed Italy and prevented it from joining the modern world. Venice, beloved by foreign tourists, was dismissed as “Europe’s brothel”. Art critic John Ruskin, who had celebrated Italian cultural heritage, became an enemy figure.

William Downey (1829-1915)

The Futurist manifesto even contained a self-consuming logic. It declared that when Marinetti himself turned 40, younger futurists should throw him “into the trash can, like useless manuscripts”. The movement advocated not just destroying museums once, but periodic cleansing of cultural memory. Nothing could be allowed to accumulate tradition or meaning.

The seeds of destruction were there from the beginning. Marinetti glorified war as “the world’s only hygiene” and promoted aggressive Italian nationalism. When the Futurist Political Party merged with Mussolini’s Fascist movement in 1920, artistic vision was subordinated to political power. The philosophical contradictions, celebrating individual creative genius while demanding conformity to nationalist ideology, created tensions that made the movement culturally irrelevant even as it gained political influence.

Five Things That Went Catastrophically Wrong

1. Glorification of Violence and Destruction

Italian Futurism didn’t just accept violence as a historical reality. It actively celebrated war, aggression, and destruction as aesthetic and moral goods. The movement embraced Italian expansionism and cultural supremacy, making technological progress inseparable from domination. Rather than synthesizing past and future, Italian Futurism sought to obliterate history entirely, creating a vacuum that fascist ideology eagerly filled.

This pattern wasn’t unique to Italy. The source material connects Futurism to similar state-sponsored iconoclasm in revolutionary France, Soviet Russia, and Maoist China. When modernization ideology justifies cultural destruction, it creates dangerous precedents. The logic always sounds progressive at first: we must destroy the old to make way for the new. But that destruction rarely stops where its advocates promise.

2. Absence of Ethical Guardrails

The movement valued technology and speed for their own sake, with no moral framework to guide their application. Machines were beautiful because they were fast and powerful, not because they served human flourishing. This absence of empathy-centered design principles meant that when political power beckoned, the movement had no philosophical foundation to resist authoritarianism.

Marinetti viewed Italy’s cultural heritage not as something to be honored or reinterpreted, but as a burden to be liquidated. There was no question of what wisdom traditions might offer, no consideration of what future generations might need from the past. Speed was the only value.

3. Authoritarianism Over Democracy

Italian Futurism began with anti-monarchist and anti-clerical positions, challenging established power. These principles were quickly abandoned when Marinetti saw opportunities for influence within Mussolini’s regime. The movement became a propaganda tool, with artistic vision subordinated to the authoritarian state. Individual creative genius, once celebrated, was channeled into serving nationalist ideology.

4. Exclusionary Cultural Supremacy

Italian nationalism and cultural dominance were core tenets from the start. There was no space for pluralism, interfaith dialogue, or universal design principles. The aggressive rejection of tradition created a vacuum where fascist ideology could flourish, as the movement offered speed and violence but no sustaining vision of human connection. Not to mention that the regime implemented Italian Racial Laws in 1938, introducing discrimination and persecution against Jews of Italy.

The humiliation Marinetti felt when tourists treated Italy as a museum of the past was real. But his response, to erase that past entirely rather than build new futures in dialogue with it, became toxic. Cultural sovereignty doesn’t require cultural amnesia.

5. Aesthetic Without Substance

When Mussolini refused to make Futurism the official state art of fascist Italy, the movement collapsed into cultural irrelevance. Decades of manifesto-writing had produced style over philosophical depth. Without a sustainable ethical foundation, Italian Futurism had nothing to offer once political winds shifted.

The movement’s self-consuming logic guaranteed this outcome. If nothing is allowed to accumulate meaning, if every generation must destroy what came before, then no stable cultural foundation can ever form. You can’t build futures on ground you keep setting on fire.

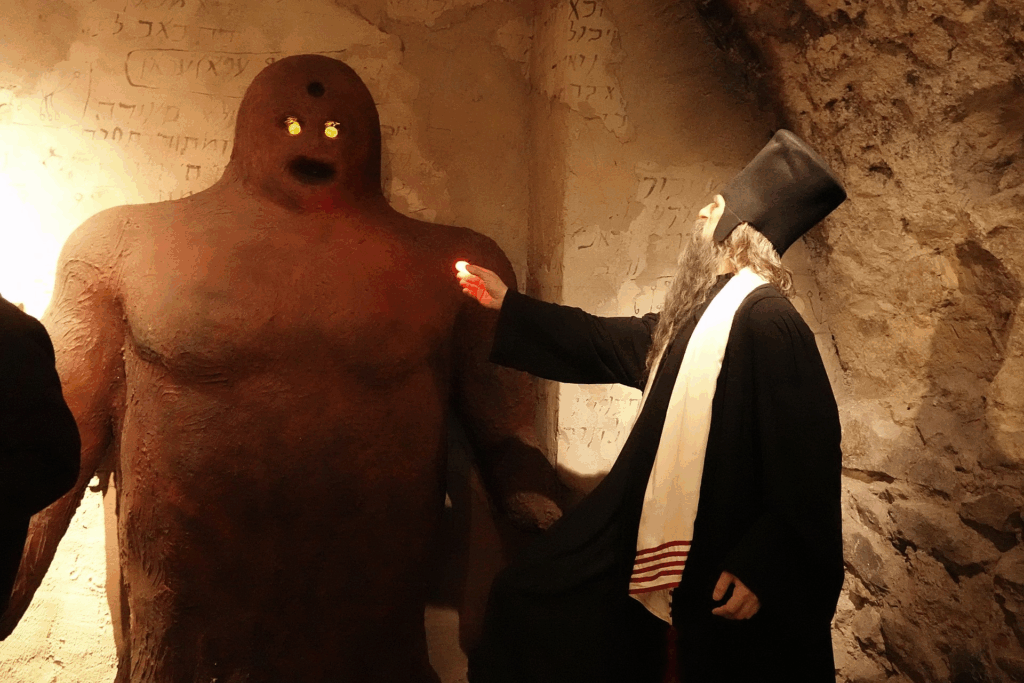

Jewish futurism: Building From Different Ground

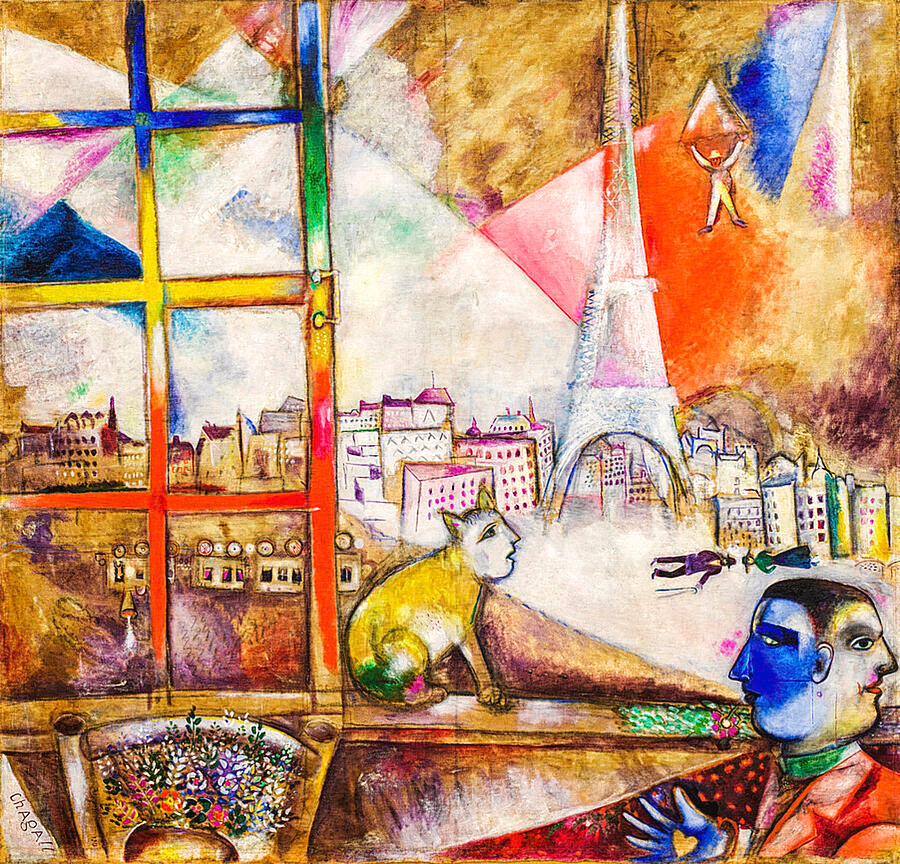

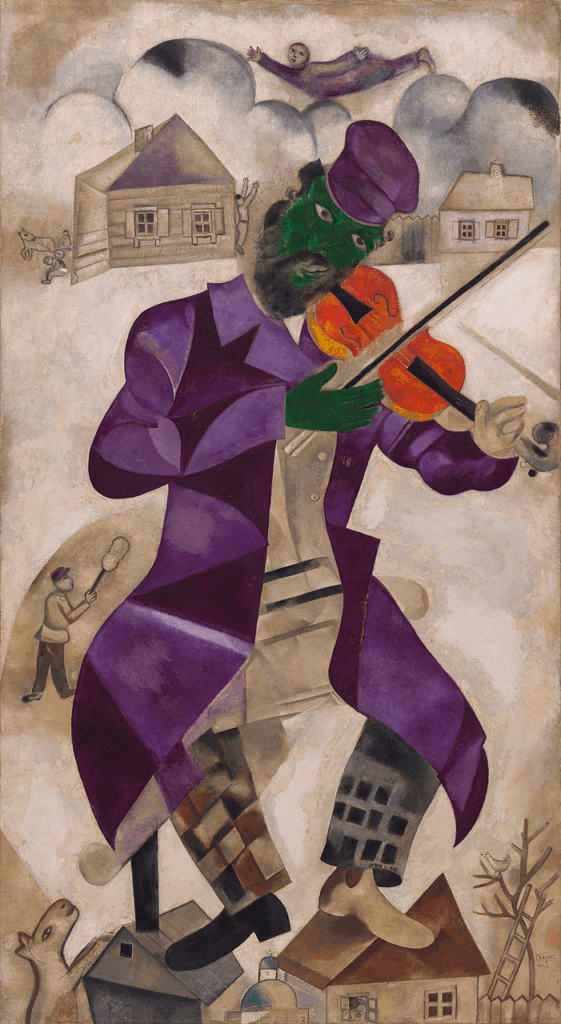

This is where my work begins. Jewish futurism emerges from fundamentally different premises, offering a model for how technological optimism can coexist with ancient wisdom and ethical responsibility. Where Italian Futurism glorified destruction, Jewish futurism centers empathy-led innovation, positioning technology as a tool for meaning-making rather than domination.

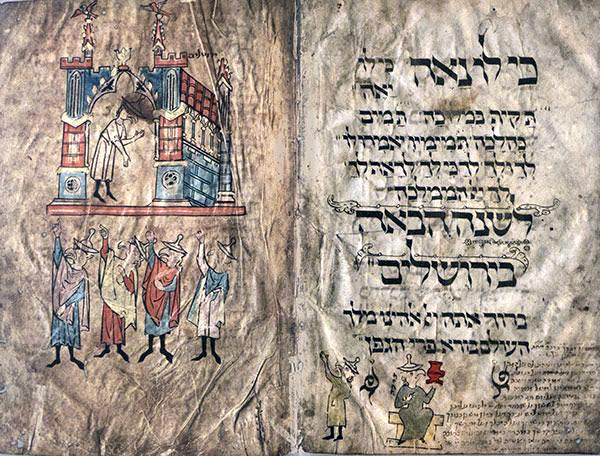

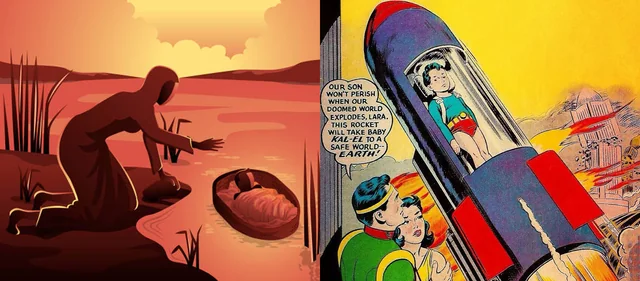

Jewish history demonstrates millennia of resilience and reinvention without destroying the past. Continuous reinterpretation, of texts, traditions, cultural practices, allows Jewish communities to honor ancestral heritage while embracing modernity. This mirrors Afrofuturism’s Sankofa principle, which emphasizes learning from the past to inform future trajectories. Rather than revolutionary destruction, Jewish futurism practices synthesis and transformation.

In my own practice, Jewish futurism is rooted in Jewish thought: tikkun olam (repair of the world), justice, responsibility. Technology is never valued for its own sake but always in service of deeper moral commitments. This philosophical grounding provides the ethical guardrails that Italian Futurism catastrophically lacked. The question at the heart of my work is: “What kind of ancestor will you be?” That question changes everything.

Where Marinetti wanted to be thrown in the trash at age 40, Jewish futurism asks what we’re building that will outlast us, what we’re passing down that future generations will need. It’s not about preserving everything unchanged. It’s about being in active, creative dialogue with tradition while we build what comes next.

What We Can Learn: Five Lessons for Building Responsible Futurisms

Ethics Must Precede Aesthetics: Beauty and innovation without moral grounding enable atrocity. Technology requires wisdom traditions to guide its use. Speed without wisdom is just velocity. It doesn’t know where it’s going or why. When Marinetti proposed selling Italy’s art heritage in bulk, he showed what happens when aesthetic ideology overrides ethical consideration.

Honor the Past While Building the Future: Synthesis surpasses destruction as a strategy for cultural renewal. Tradition provides foundation for innovation rather than serving as an obstacle to it. Jewish tradition treats time as cyclical rather than linear, where past, present, and future dynamically interact. The humiliation Italy felt at being treated as a museum was real, but erasure isn’t the only response. We can acknowledge what’s broken in our inherited traditions while keeping what sustains us.

Center Human Dignity Over Cultural Supremacy: Universal design principles create futures for all people, not just dominant groups. futurism must be liberatory rather than oppressive, replacing nationalism with empathy and collaboration. Jewish futurism creates shared spaces for collective growth and interfaith collaboration. The pattern of state-sponsored iconoclasm, from revolutionary France to Soviet Russia to Maoist China, shows us what happens when one vision of the future tries to erase all others.

Resist Political Opportunism: Artistic movements must maintain ethical independence even when political power beckons. When survival requires moral compromise, the movement has already failed. Marinetti’s compromises to ensure the movement’s survival hollowed it out from within. The proposals to liquidate cultural heritage weren’t just aesthetic statements. They were political calculations about access to power.

Root Innovation in Community: Collective meaning-making replaces the cult of individual genius. As I’ve learned in my own practice, the future, like design itself, is fundamentally a team sport. It thrives when we create collectively and collaboratively. Collaboration and care supersede competition and domination. The Futurist manifesto’s call to throw Marinetti himself in the trash at 40 reveals a movement with no concept of intergenerational continuity, no way to pass wisdom forward.

The Responsibility of Imagining Futures

Every speculative vision carries political and ethical consequences. Italian Futurism’s trajectory from revolutionary art movement to fascist propaganda machine demonstrates that enthusiasm for the future, absent ethical grounding, can enable profound harm.

When I stand in front of my design students at Queens, looking at those bold Futurist posters, I don’t want to just critique them. I want to show what it looks like to rescue the core impulse, the courage to imagine radically different futures, from what got corrupted. The frustration Marinetti felt was real. Italy was stuck. The weight of the past was crushing. Foreign tourists treating the country as a beautiful corpse was genuinely humiliating. But his solution, to burn it all down and start from nothing, created more problems than it solved.

Jewish futurism offers that alternative model: technological optimism rooted in ancestral wisdom, innovation guided by empathy, futures built through synthesis rather than destruction. We can honor what we’ve inherited while transforming it. We can be critical of traditions that harm while keeping what sustains. We can build futures that acknowledge the past without being imprisoned by it.

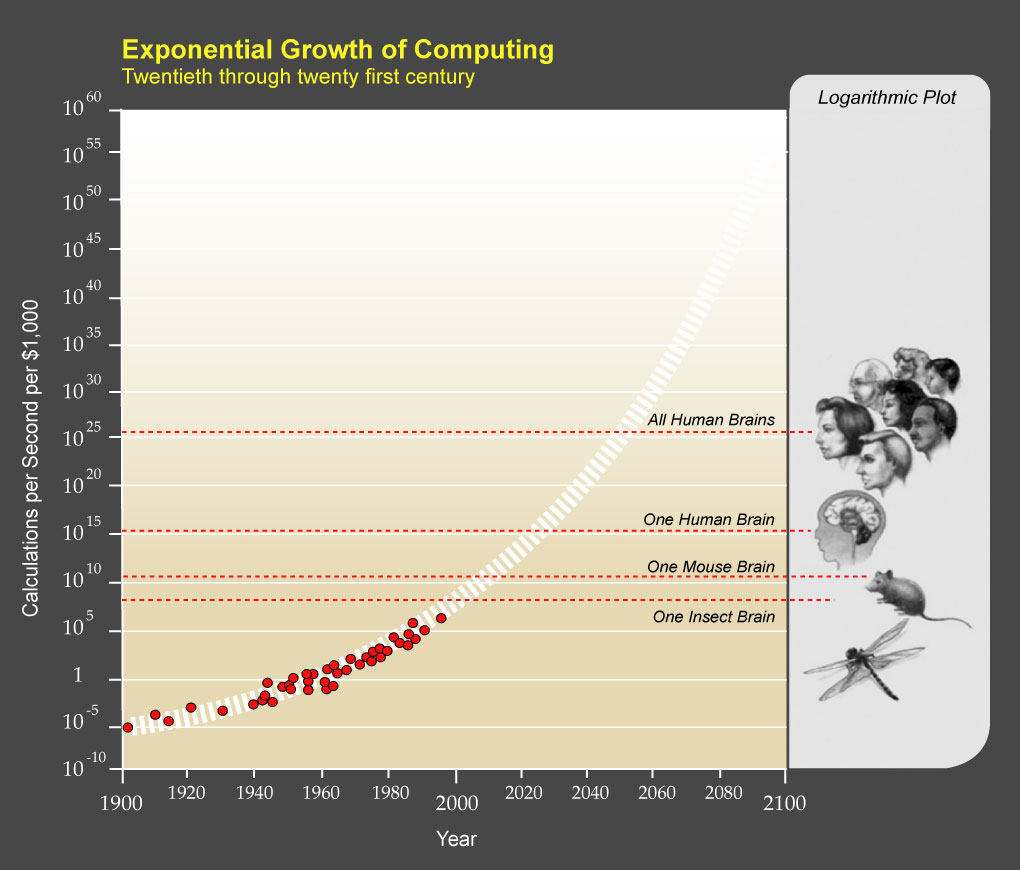

The question isn’t whether we’ll imagine futures. In periods of technological transformation, futurist movements will inevitably emerge. The question is what values will guide those visions. Will we learn from history’s warnings about the price of speed without wisdom, aesthetics without ethics, innovation without responsibility? Or will we repeat Italian Futurism’s mistakes with new technologies and new manifestos?

I’m betting we can do better. Jewish futurism, and the broader family of ethical futurisms it’s part of, shows us how. We can be bold and careful. We can embrace transformation and honor memory. We can design futures that are actually livable, not just fast. That’s the work. That’s what I’m trying to build.