An Essay on ADHD, Flow, and Revelation Through Pattern

Introduction: Where Neurodivergence Meets Jewish Futurism

Neurodivergent people are often told our brains need fixing. Jewish tradition is often told it needs preserving, frozen in amber to survive. Both framings are wrong, and both miss the same truth: difference isn’t deviation, it’s design principle.

I have the unique pleasure of being Jewish, neurodivergent, and an artist. This intersection isn’t burden or coincidence. It’s the source of my creative and spiritual practice. This essay argues that neurodivergence and Jewish futurism aren’t just compatible frameworks, they’re overlapping systems that reveal each other’s deeper possibilities. My late ADHD diagnosis showed me that the creative and spiritual practices I’d developed weren’t workarounds for a broken brain. They were Jewish futurist methodology, and my neurodivergence was the engine driving it.

Jewish futurism, as I define it, is a design methodology and creative practice that imagines ethical Jewish futures without freezing the past or erasing identity. It recognizes that Jewish civilization is closer to its beginning than its end, requiring radical idea development rather than preservation of fixed forms. Rather than asking “how do we preserve Shabbat as it was,” Jewish futurism asks “what does rest look like in a future we design?” Neurodivergence operates on similar principles. A neurodivergent brain resists linear, settled narratives. It sees patterns others miss, makes unexpected connections, and questions endlessly. Both frameworks reject the notion that there’s one correct way to think, create, or practice. Both demand that we build new systems rather than simply accommodate ourselves to existing ones that weren’t designed for us.

The overlap is way more than just metaphorical. Jewish practice has always contained practices that change how we think and feel: repetitive prayer motion, textual wrestling, embodied ritual. Neurodivergent minds have always sought ways to access flow states (shefa in Hebrew), regulate brain chemistry, and channel intense perception into creative work. When these two meet, something revelatory happens. Ancient wisdom reveals itself as neurodivergent technology. Neurodivergent experience reveals itself as a form of prophetic sight.

The Cloud of Noise

In the late 1980s, I stood before Jackson Pollock’s Lavender Mist at the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC and felt my world tilt. The painting’s scale overwhelmed me. With no subject or focal point, my eye moved constantly, never resting. The density of marks created illusory movement that simultaneously pushed and pulled me. I wasn’t seeing anything sinister. The optical effects themselves stimulated my young brain in a way I’d never encountered before. The disorientation frightened me because I’d lost control of my own perception.

Decades later, when my doctor asked if I could remember childhood moments of sensory overload, this returned to me. But it’s also the story I tell about falling in love with art. My neurodivergence wasn’t separate from my artistic calling. It was delivering information through my body, through sensation, showing me a path I would spend my life following. I would later learn that ADHD brains don’t produce enough dopamine naturally, the neurochemical that regulates focus, motivation, and pleasure. This means my brain is constantly seeking stimulation, novelty, and intensity to feel what neurotypical brains get more easily. It also means that when I find the right stimulus (complex patterns, rhythmic motion, creative flow), I can hyperfocus with an intensity that feels transcendent. This isn’t a disorder to fix. It’s a different operating system that needs different fuel.

The All-Night Dance

I realized art-making could produce that fuel in college during the late 90s. I had procrastinated on a large painting for class, one of my mosaic-like pieces built from tiny dashes, dots, and patterns. Now I faced an all-night session with the piece due at 8am.

Panicking, I cranked up music and danced my frustration away. I hadn’t yet learned to daven (the rhythmic, often swaying motion of Jewish prayer), but I knew how to headbang. The swaying motion of my brain (probably bouncing off the inside of my skull) gave me a surge of energy and focus. That launched an all-night painting dance. The first time I felt it.

A floormate studying art therapy explained that creativity and flow were connected. It stuck with me. When I’m in that state, I’m moving, dancing, pausing, getting back up and working. Eventually it all becomes rhythmic. Stopping can be hard because I love the feeling. My brain is finally getting the dopamine it needs, and it feels like coming home.

Discovering Shefa Before Diagnosis

Before my ADHD diagnosis, I began practicing Jewish meditation and connected with the ecstatic state that emerges from davening. When I worked up faster and faster in motion, I entered an ecstatic state producing focused, euphoric sensation. This showed how deep into flow I had gone. In Jewish mystical tradition, this is called shefa, the flow of divine abundance. That flow is holy and sacred.

I developed meditation as a way to enter flow state on demand. When I had creative work with limited time, I couldn’t noodle around waiting for the zone. I needed a technique to get there in minutes. Meditation does this for me. What I didn’t understand then: my neurodivergent brain was seeking the dopamine regulation it craved through ancient Jewish practice. The practice was already there, waiting for my body to recognize it as both medicine and revelation.

The Late Diagnosis as Renarration

My late ADHD diagnosis functioned as a Jewish futurist act of renarration. Jewish futurism rejects nostalgia that freezes the past. A late diagnosis forces you to reinterpret your entire history through a new lens. Experts describe a 2-3 year period of deepening self-awareness and making sense of the past while getting to know yourself perhaps for the first time. This mirrors Jewish practice of wrestling with text and meaning, returning to the same stories and finding new interpretation. In Hebrew, this return is called teshuvah, and it doesn’t mean going backward. It means turning to face something you couldn’t see before.

I worried that medication and therapy would dull or damage my creativity. Thank God it didn’t. Instead, I finally felt focus and clarity like I’d never known. The drawbacks shifted. Learning to stop became a new challenge because I can get so hyperfocused that I lose the sense of time completely. I’ve set alarms for work time now. While time management was never my strength before diagnosis, I’m now hyperfocused and productive instead of procrastinating and wasting time.

This is Jewish futurist methodology: using constraints and identity to design ethical, sustainable futures. Setting alarms isn’t giving up on natural creative flow. It’s designing a life where I can create without burning out. It’s building a future that works with my brain, not against it.

Returning to Lavender Mist

When I looked at Lavender Mist again as a photo online after my diagnosis (I haven’t returned in person yet), I anticipated the sensation. This time I felt like I could be inside the painting. I could follow individual splashes of paint throughout the entire piece. It seemed to pulse like neurons. Maybe it’s because I’m older and have studied the work for 35 years. Maybe it’s something else.

What appeared as a cloud of noise in childhood now reveals the complex interconnectedness of the universe and our lives. My pattern recognition explains why I remember flags, logos, fonts, and motifs with uncanny precision. As a kid, I spent hours memorizing the flags in my family’s encyclopedia books. When I didn’t quite understand what I was seeing and it altered my physical balance or other sensations, I craved it.

This craving led me to love jazz as a teenager, dive into complex video games, and eventually learn BASIC, HTML, CSS, JavaScript, Java, PHP and MySQL. I built a career in multimedia, infographics, illustration, and interactive installations. I’ve always been chasing the feeling those early experiences showed my brain. I suspect I’m not alone in this. Many neurodivergent artists, coders, musicians, and designers describe similar origin stories: an early overwhelming encounter with complexity that felt like a calling.

Teaching Flow States

With therapy and treatment, my self-awareness lets me focus more on my students’ states. I have hours of meditation practice and training that I now relay to my students. The methods and practices my therapists and mentors taught me, my resources, literature, and guidebooks are open to them. I observe when students enter and exit flow states.

I now weave sensory-friendly methods into my classroom curriculum. I guide students through sensory-friendly design practices. I set outcomes and classroom practices using timers, reminders, and feedback-centric approaches to projects.

One example: I use a digital whiteboard to doodle and lecture. I pause my lecture to allow students to reflect and doodle on my slides or drawings. My therapists say those brief pauses give my brain time to catch up. They give neurotypical people a moment to rest and reflect as well.

Building in transitions allows flow to extend learning and enables pivots to new topics or activities without harsh interruption. These practices don’t just help neurodivergent students. They make learning more sustainable and creative for everyone. This is ongoing. I still have loads of questions. Luckily, I have colleagues who are music therapists at my university. I want to work with them to learn more.

Prophecy Through Sensation

I could say these feelings were prophetic, though they didn’t come with instructions. Only feelings. I wasn’t told to go forth. I was given the physical sensation that my brain loved, and I knew I should follow it into my future. Powerful. Looking back, it could have been prophetic.

The Pollock moment wasn’t isolated. In the late 90s, I heard Dave Brubeck’s “Blue Rondo à la Turk” and lost my mind. I’d never heard 9/8 time before and it was an experience to be had. Parts of my brain were firing for the first time. In the late 2000s, reading Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower, a book gave me this sensation for the first time. When I painted my first mural in college, I felt it too. Each time, my body told me: this matters, follow this.

This sensation guides my creative problem-solving. When I built a microcontrolled LED pomegranate sculpture, the solution appeared in my imagination. I knew I wanted specific patterns and wrote code to simulate them. The solving came from trying out code ideas rather than looking up answers. I felt like I had it in my head and didn’t want to jump ahead. I would have felt bad, like I skipped a step and missed the chance to connect to the problem more deeply than just using an answer. When I get a taste of that Jackson Pollock feeling, I know the idea is worthy to act upon.

I see these prophetic moments in my students. In 2012, I taught a digital installation course where students built interactive experiences with projectors, cameras, and software. This was a challenge many had never faced, and there was no real framework for it. The students stayed in the lab longer than I’d ever seen. Each one was hyperfocused on coming up with a great idea and executing it. One student made a cubist magic mirror. Participants would look into the camera and see their face broken into multiple planes like a cubist painting. It was a technical achievement and an exciting concept. This student could achieve deep focus, and I was overjoyed. I watched them receive revelation through the making itself.

My meditation practice has delivered visions that became art. After I read the legend of the Sambatyon River (a legendary lost river where the lost tribes of Israel are said to be on the other side), it appeared in my head as a complete image. I illustrated it as an art piece. It was amazing to bring that clear and crystallized vision to life. I want to one day make it an immersive interactive digital experience for people in a gallery. How amazing to reconnect with the lost tribes through sensation and technology.

This is the question I’m sitting with now: what if prophecy today arrives not as commandment but as sensation? Rather than a booming voice with harsh instructions like Moses received, perhaps prophecy today is a neurological connection born of overwhelming encounter with beauty or complexity. Perhaps neurodivergent people, who feel sensory input more intensely, are receiving information that neurotypical perception processes more quietly.

I think art functions as revelation for neurodivergent people in this way, which makes art therapy crucial to intersect with neurodivergent experience. Because we feel so deeply (words, pictures, information, pattern, sound), we can embody it in ways that catalyze transformation. We don’t just see the painting or hear the music. We feel it rewire our nervous system. We receive direction through our bodies.

AI as Neurodivergent Technology

AI has become a second brain for my ADHD practice. It helps me go down rabbit holes with purpose and stay on track when I get lost. It lets me use my own entrance points into thinking and learning through conversation. I love having it roleplay scenarios and offer critique to get another perspective, especially at 2am when I might be working and no human collaborator is available.

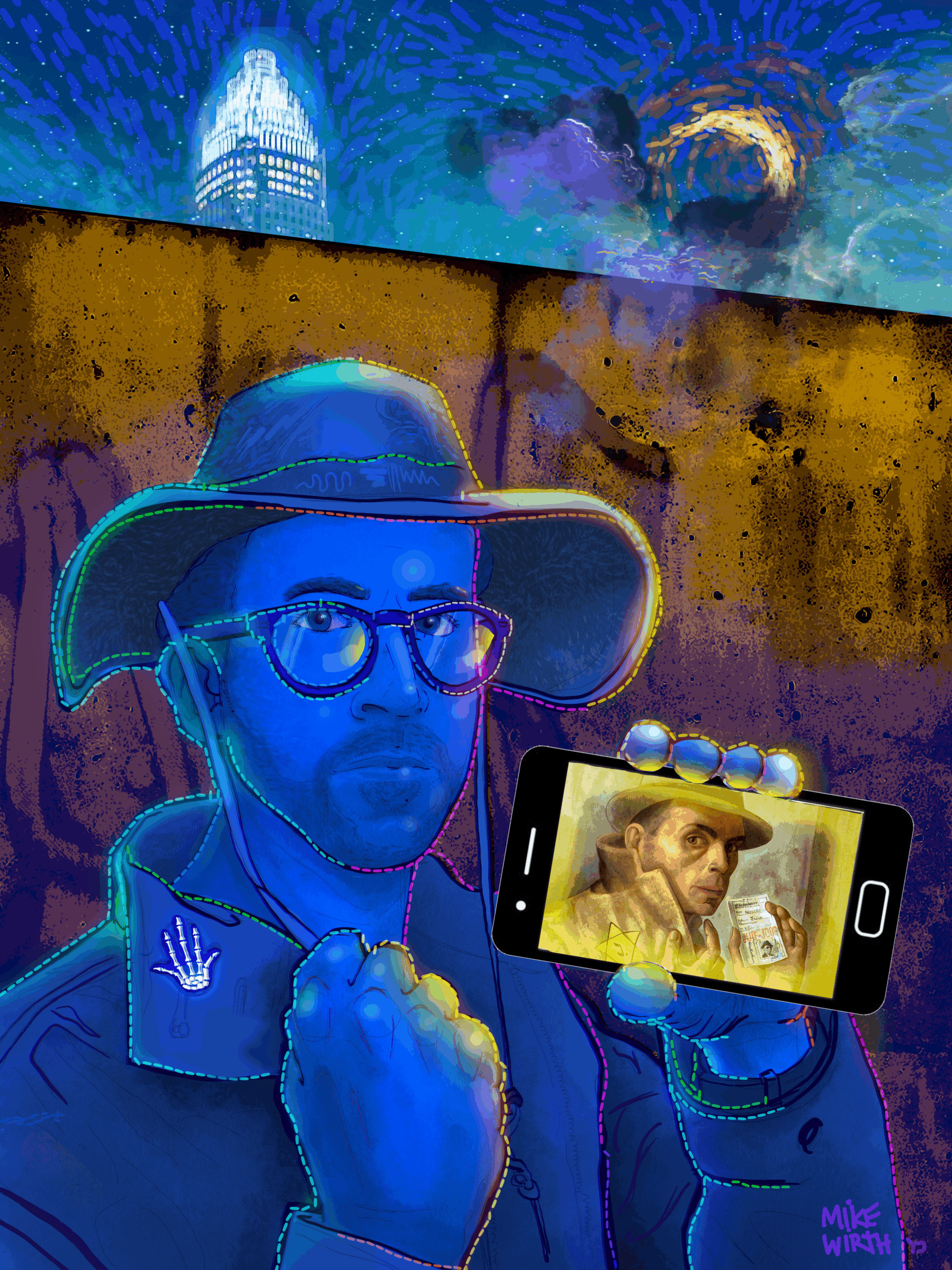

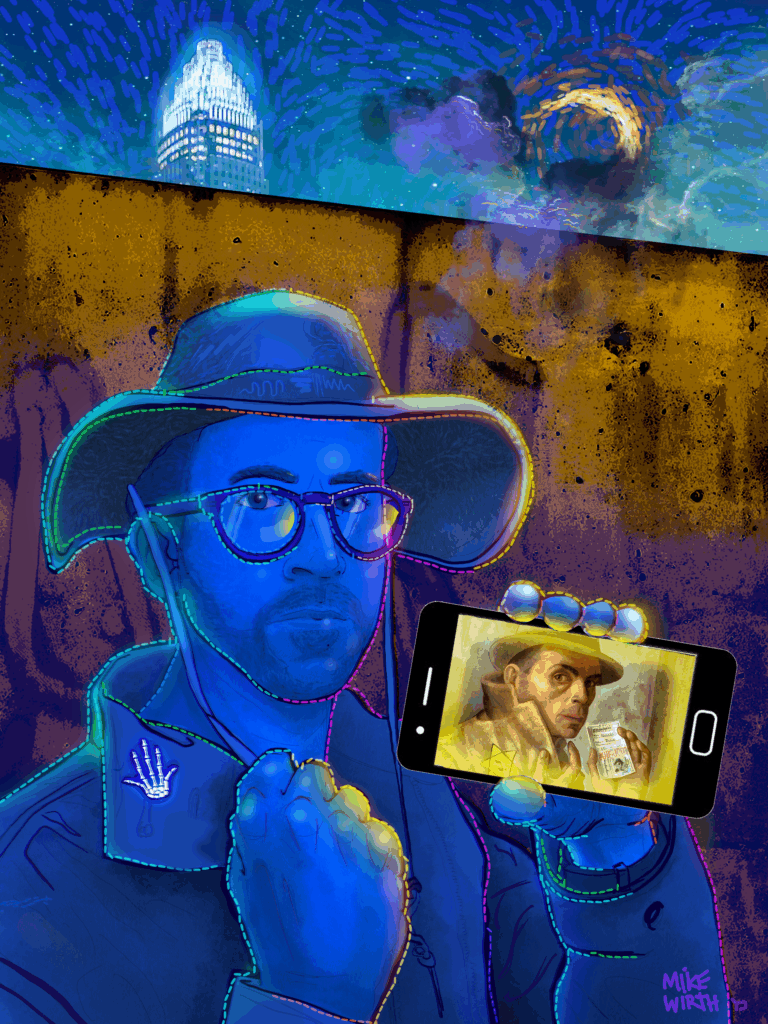

I use LLMs regularly. I run DiffusionBee with my own custom fine-tuned image model based on hundreds of images of my own work. I use NotebookLM to make infographics and slide decks for students in my design history class. I help students use AI to vibe-code or troubleshoot issues with digital projects. Before AI, staying organized and fighting the paralysis of starting to write were my biggest challenges. Now I use my custom-trained AI model to sketch with. I can pose any character into a new image, allowing me to expand my body of work into new camera angles and compositions. This has pushed me beyond what I could do alone.

The relationship to flow state is complicated. If I jump to AI too early, I usually get weak output because I don’t yet know why I’m doing what I’m doing. Without human purpose, AI feels like a toy. But it speeds up the juxtaposition process dramatically. I can merge, twist, blend, and oscillate images in a fraction of the time I could on my own using Photoshop and collaging elements together to make references to paint or draw.

It feels like both collaboration and assistance. There are tasks I can delegate to AI so I can focus on the grand vision and be the final editor saying yes or no to my idea manifested as a sketch. I still rewrite what AI gives me even if it’s good or better than what I could do. I can feel “that’s not my voice” after a quick read. This editing process is where I connect to the work.

AI and Jewish Futurist Practice

AI helps me explore the divergent ideas I get about interpreting Torah or Kabbalah. It’s an assistive chevruta partner (a traditional Jewish study partner) when a living one isn’t available. Often I use it to help me think about how a Jewish futurist idea might unfold over a long period of time or what impacts I might be missing or overlooking. I appreciate those bits of what AI can do for my practice. Sometimes it shares profound ideas and helps me see what I might be assuming about my thoughts. It’s helped me develop my thoughts to be more accessible and inclusive.

I teach my students about AI and share my appreciation as an ADHD user, but I teach in a neurodiversity-friendly way and don’t specifically focus on that unless a student asks me. I want all students to see AI as a tool that can work with their brain, whatever their neurotype.

The complications are real. LLMs can be overwhelming. Prompting can lead to dead ends without help. The technology is harmful to the planet, which makes me use it sparingly and offline or locally on my computer whenever possible. I’ve led the way to use these tools on personal computers rather than via web browser and data center, reducing the intensity of greenhouse gases. I’ve needed to write something personal fast and entered vague prompts that produced very weak output. After a few more attempts with no luck, it frustrated me so much I shut the computer and wrote it myself.

This tension is Jewish futurist thinking in action. How do we use powerful tools ethically? How do we build sustainable practices that don’t extract more than they give? I set instructions to my chatbot to not give me answers but to have a conversation and build an outline. This helps me organize my chaotic thoughts. Then I leave the chatbot with a product I can use to write by hand. The AI doesn’t replace my thinking. It scaffolds it so my neurodivergent brain can do what it does best: make unexpected connections, see patterns, and create something that didn’t exist before.

Neurodivergent Jewish Futurism

Jewish futurism suggests that Jewish civilization is closer to its beginning than its end. This requires radical idea development rather than preservation of fixed forms. My ADHD brain doesn’t accept “this is how it’s always been” as an answer. That’s precisely the mindset needed to imagine ethical Jewish futures that don’t freeze the past or erase identity.

Neurodivergent minds naturally resist linear, settled narratives. We favor pattern recognition, connection-making, and questioning that never stops. The Talmudic tradition, the central text of Jewish law and ethics built on centuries of debate and commentary, may itself reflect neurodivergent thinking patterns through its attention to detail, organizational systems, and endless questioning.

What makes this Jewish futurism: my story demonstrates how neurodivergent experience isn’t a deviation from Jewish practice requiring accommodation. It’s a particular intensity of engagement with practices already designed to alter consciousness. My childhood terror before Lavender Mist, my college discovery that headbanging unlocked creative flow, my pre-diagnosis discovery of shefa through davening, my post-diagnosis ability to track individual paint splatters as neural pathways. These aren’t separate experiences. They’re the same neurodivergent capacity to perceive overwhelming amounts of information as sacred pattern.

Jewish futurism asks: how do we design ethical, sustainable Jewish futures that don’t freeze identity or erase difference? My answer, embodied in my creative and spiritual practice, recognizes neurodivergent perception as prophetic sight that comes through sensation rather than instruction. We build techniques (meditation, alarm systems, rhythmic prayer, sensory-friendly pedagogy) that allow neurodivergent bodies to access flow sustainably. We teach that the overwhelm itself, when it comes from encountering beauty or holiness, is shefa.

Closing

I’ve been chasing the feeling Lavender Mist gave me for 35 years. In doing so, I’ve built a Jewish futurist practice that centers a simple truth: neurodivergent brains aren’t broken. We’re receiving revelation through channels that neurotypical perception might miss entirely.

If you’ve ever felt overwhelmed by beauty, if you’ve ever found focus through repetition, if you’ve ever sensed that your different brain perceives something others miss, you might be receiving revelation too. The question isn’t whether you’re broken. It’s what you’re being shown, and what futures you’re being called to design.