During my semester long sabbatical, I set out to experiment with new ways to tell Jewish stories, and I kept coming back to the immersive feeling of games. While I stayed focused on my main objective, completing my book Hiddur Olam: Bereshit – Genesis and telling new Jewish stories through art and writing, this Hanukkah, I also felt a pull to expand this idea of immersive storytelling into video games, where players could step inside the work rather than only view or read it. Framing the game projects as interactive midrash let me treat code, mechanics, and level design as another layer of commentary on the same questions that animate the book: how to re engage with foundational Jewish narratives, how to honor tradition while playing with form, and how to imagine Jewish futures that feel both grounded and newly alive in digital space.

Vibe coding and my AI toolbox

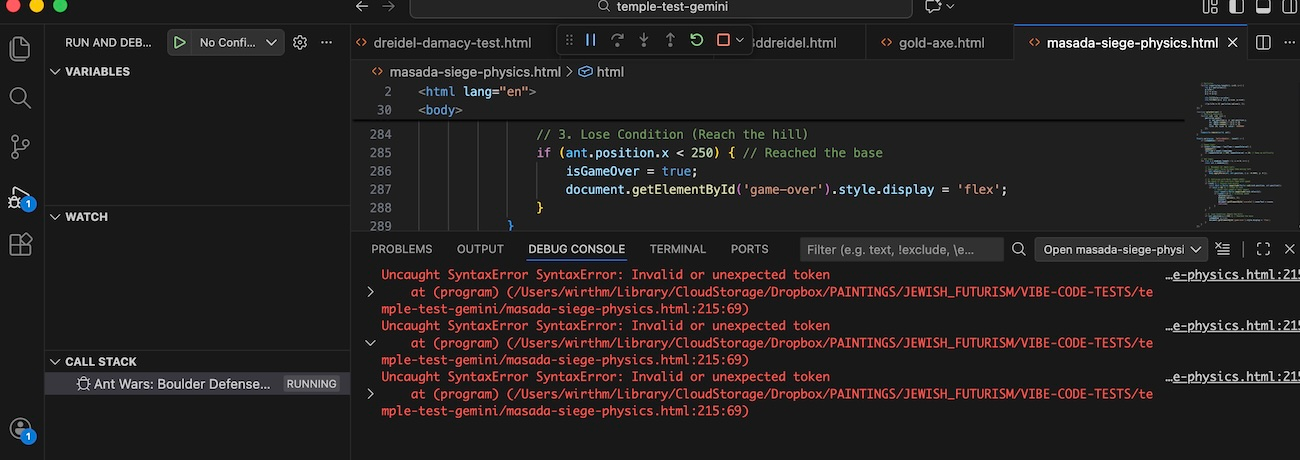

For all of these projects, I leaned heavily on what I think of as vibe coding. By vibe coding, I mean describing in natural language how I want something to feel, look, or behave, then using AI coding tools to generate or refactor code until the game’s behavior matches that feeling. I used ChatGPT, Gemini, and GitHub’s coding assistants as a rotating team, asking for everything from small bug fixes and refactors to full systems like player controllers or state machines. I have 20 years of front-end and back-end web development coding experience. Having been a part of a wave of student designer-artist-coders in NY in the late 90s and early 00s making websites by day and net-art by night, vibe coding is great method to make code sketches of ideas or experiments. In this project, I would move the same block of code from one model to another when I got stuck, wanted new insight, or when I wanted to shift from quick procedural hacks into a more object oriented structure. Each of the the different LLM code “voices” helped me see new paths through the same problem. These tools gave me a sense of freedom to soar with code, where in the past I would have been creeping along, slowly teaching myself new methods and getting bogged down in syntax rather than in the Jewish and ludic questions that actually interested me.

Research questions that guided me

A cluster of questions ran through everything I made:

- How can I evolve dreidel gameplay beyond a single spin and four letters?

- With only four sides, can a dreidel still function as a rich, reusable dice object in a larger game system?

- Can the dreidel be used more effectively to tell the story of Hanukkah, not just reference it visually?

- What are better ways to tell the story of Hanukkah using the immersiveness of games?

- How can I tell new digital Jewish stories that feel both grounded in tradition and native to contemporary game culture?

- Is this creative act, moving ritual objects into speculative, interactive worlds, an example of Jewish futurism in practice?

- How will Jewish people play dreidel in the future?

Each experiment became a different argument or provisional answer to these questions.

So, over 8 nights, I played with various game and interaction experiments. Here are my best of the best, in no particular order.

Dreidel Run: Neon Grid

Best for dreidel kinetics

With Dreidel Run, I leaned into the question of how to evolve dreidel gameplay at a purely kinetic level. Here, I made the case that the dreidel can succeed as a contemporary and arguably futuristic game mechanic when it is allowed to be fast, flashy, and even a little mindless, while still anchored in

Hanukkah imagery like gelt and glowing colors. Using the Temple Run game mechanics, the experiment argues that not every Jewish game needs an explicit narrative lesson, and that embodied fun, quick reflexes, and the pleasure of catching coins and dodging hazards can themselves be a form of connection, a way of feeling Hanukkah as energy and rhythm rather than only as a story told in words.

Dreidel x Katamari mashup

Best for dreidel physics

In the dreidel and Katamari Damacy inspired mashup, I took seriously the question of whether a small, four sided object could scale up into a world building tool. The design argues that as the spinning dreidel absorbs gelt and grows, it enacts a kind of visual and mechanical midrash on Hanukkah’s themes of accumulation,

excess, and the tension between material things and spiritual light. By exaggerating the physics, I could show how a simple ritual object might literally reshape its environment, and in doing so, I tested how far dreidel based mechanics can stretch before they stop feeling like dreidel play and become something new. Another fun way to play with the dreidel kinetics.

Dreidel Physics Sandbox

Best Holiday Stress Reliever

The smaller dreidel physics sandbox experiments addressed the quieter research question of how players might encounter Jewish content without a fixed goal at all. The spinning battle top game transforms the dreidel into a tornado like object tasked to destroy Seleucid idols of the Temple. It’s instant gameplay makes the argument that

open ended, low stakes experimentation can be a valid form of digital Jewish learning, where the “lesson” is not amoral but a felt sense of spin, friction, wobble, and collapse. In the second experiment I used the Marble Madness type game play, making the dreidel become

a tiny lab for thinking about stability and risk, which echoes Hanukkah’s precariousness, and invites players to linger, tinker, and waste time in a way that is still charged with symbolic possibility. These were worthwhile explorations of the exciting and kinetic nature of the dreidel game.

Dreidel Catan prototype

Most conceptual

In my Catan style prototype, I explored whether a four sided dreidel could act as a meaningful dice object inside a complex resource and territory game that could help tell the story of Hanukkah in terms of the Maccabees, Hellenized Jews, and Seleucids as groups competing for resources and domination in Jerusalem. The design argues that it can, because each side of the dreidel already carries narrative weight, and that weight can be elevated when paired with a card, tableau and board game system like Catan. Resource bonuses, penalties, or events that shape a shared board.

By letting the dreidel drive the different outcomes for each player I was curious to replace the dice with two dreidels. Pushing the game narrative of dreidel from a closed loop into a network of context specific effects.While buggy and complicated, this was one way that Hanukkah themes of scarcity, risk, and negotiation might live inside a modern strategy game.

Hanukkah Quest 1: The Temple of Gloom

Best for Hanukkah story

Hanukkah Quest 1: The Temple of Gloom tackles the question of how to better tell the story of Hanukkah with the immersiveness of a game. Here, I argue that interactive midrash is possible when puzzles, jokes, and spatial navigation all serve as commentary on the holiday’s themes, such as hiddenness,

illumination, desecration, and rededication. Instead of retelling the miracle in a linear script, the game invites players to stumble through a gloomy, playful temple and slowly piece together meaning from their own actions, which models a Jewish way of learning that is iterative, interpretive, and grounded in wandering and return.

Jewish futurist wisdom

These experiments do not just gesture toward Jewish futurism, they enact it and point toward where it might go next. They show that Jewish futurism means keeping ritual objects and stories in play, while re staging them inside interactive systems where players can touch, bend, and argue with them in real time, like a digital beit midrash that anyone can enter. By dropping the dreidel and Hanukkah into arcade runners, resource economies, absurd physics toys, and point and click temples, the work suggests that the future of Jewish storytelling may live in responsive systems rather than fixed scripts, and in shared worlds that generate many valid readings instead of a single correct answer. Your vibe coding practice, using AI to rapidly prototype and reconfigure these systems around a felt sense of Jewish meaning and play, is a clear example of Jewish futurism in practice, and it opens hopeful paths forward: networked Jewish game spaces, collaborative “midrash servers,” classroom rituals that unfold as playable worlds, and future projects where new holidays, communities, and speculative texts are first tested as games before they are written down. In that sense, these games are not an endpoint but a launch pad, a sign that Jewish life will keep unfolding inside new technologies, still circling the same core questions of memory, risk, light, and communal responsibility, while inviting the next generation to help code what comes next.