Images included are used solely for commentary and academic analysis under fair use provisions of U.S. copyright law.

During the first year of the pandemic in 2020, a friend recommended I read My Name Is Asher Lev. We had just finished watching Shtisel, the Israeli drama about a Haredi family in Jerusalem. Akiva, the show’s painter protagonist, is gentle, passionate, and deeply conflicted between his community’s expectations and his need to create (Lyons; Mazria Katz; “The Art and Politics of Desire”). His journey is like Asher Lev’s and raises a still-vital question, what makes art Jewish?

Our connection of Asher Lev to Shtisel illuminated an ongoing continuum of reinvention in Jewish storytelling and ritual. Originally a novel, Asher Lev’s journey was adapted for the stage by playwright Aaron Posner, premiering at the Arden Theatre Company in 2012 and later finding success Off-Broadway, where it won several awards including the Outer Critics Circle Award for Outstanding New Off-Broadway Play (“My Name Is Asher Lev – Dramatists”; Broadway.com; Fountain Theatre). The adaptation brings Potok’s exploration of art, faith, and family into the lived immediacy of theater, allowing new audiences to encounter and interpret these questions on their own terms. In this way, Asher Lev’s/Akiva’s conflict with tradition, creativity, and communal belonging, continues to inspire and reshape Jewish art in every new medium.

Reading Asher Lev reframed the question for me. Both Akiva and Asher are artists negotiating communal obligation and personal inspiration, risking nearly everything to remain true to their gifts. Their stories trace a path toward sacred creativity, providing a foundation for what can be called Jewish futurism.

When Chaim Potok published My Name Is Asher Lev, he gave Jewish artists an enduring guide. Potok’s Hasidic protagonist struggles to reconcile tradition and creative drive. As Potok writes, “…an artist is a person first. He is an individual. If there is no person, there is no artist” (My Name Is Asher Lev). This tension between individuality and belonging is a persistent theme in Jewish artistic life. Jewish futurism affirms that Jewish art isn’t fixed in the past; rather, it unfolds with every creative act, no matter the medium.

Potok’s novel contends that creative instinct itself is sacred. Asher paints not out of pride, but from necessity, a need that is intertwined with spiritual purpose. Potok argues, “A life is measured by how it is lived for the sake of heaven” (Potok, Goodreads). For Asher, creative intuition becomes a form of ruach elohim, the divine breath of creation.

The narrative of Asher Lev is rooted in the idea of Tzelem Elohim, the belief that each person is made in the image of God. When Asher paints The Brooklyn Crucifixion, he is not betraying his Judaism. Instead, he translates personal anguish into communal compassion (SparkNotes; LitCharts). This ability to turn emotion into understanding reflects a hallmark of Jewish artistic practice. Maurycy Gottlieb, the nineteenth-century Jewish painter, struggled in similar ways. His art often explored the tensions between personal identity, Jewish tradition, and the surrounding culture (YIVO Encyclopedia; Culture.pl; Jewish Virtual Library; Brandeis).

Like Asher Lev, Gottlieb faced societal expectations and pressures from family, peers, and the broader Jewish community. He frequently channeled his own pain and longing into works that resonate with empathy and universal dignity (YIVO Encyclopedia; Jewish Virtual Library; Brandeis; Segula Magazine). Their creative journeys illustrate how Jewish artists inspired by the concept of Tzelem Elohim bring individual and collective experience into dialogue, turning private struggles into forms of connection and healing.

Akiva’s journey in Shtisel parallels Asher’s in many ways. He transforms his family and grief into paintings, using creativity as a form of tikkun, or repair (Lyons; Mazria Katz; “The Art and Politics of Desire”). Despite resistance from his world, Akiva, like Asher, brings faith and creativity together, refusing to separate the two.

Jewish modernism’s dialogue with tradition is exemplified by Marc Chagall, whose paintings fill modern art with Jewish memory and mysticism. As Chagall observed, “If I create from the heart, nearly everything works; if from the head, almost nothing” (Chagall qtd. in “Analysis of Marc Chagall”; Grad). Chagall’s career models how Jewish creativity can look forward while remaining emotionally and spiritually grounded.

This same process of transformation is reflected in Potok’s exploration of art’s creative and destabilizing power. “Art is a danger to some people… Picasso used to say, art is subversive,” Potok reminds us (Bookey). In both modern and traditional contexts, Jewish artists risk pushing boundaries in order to offer new interpretations of spiritual experience.

Jewish spiritual practice teaches that every action gains significance through intention, or kavanah. Potok mirrors this sentiment: “Creativity, self-expression, and truth…emerge from honesty about oneself” (LitCharts). Jewish futurists apply this mindset to every new creative medium, continually asking if their work reveals more goodness and light.

Today, artists like Deborah Kass and Archie Rand carry these values forward as Jewish artists fully integrated into the mainstream art world. Kass’s OY/YO at the Brooklyn Museum and Rand’s The 613 both embody the creative tension between reverence and innovation (Brooklyn Museum; Rand).

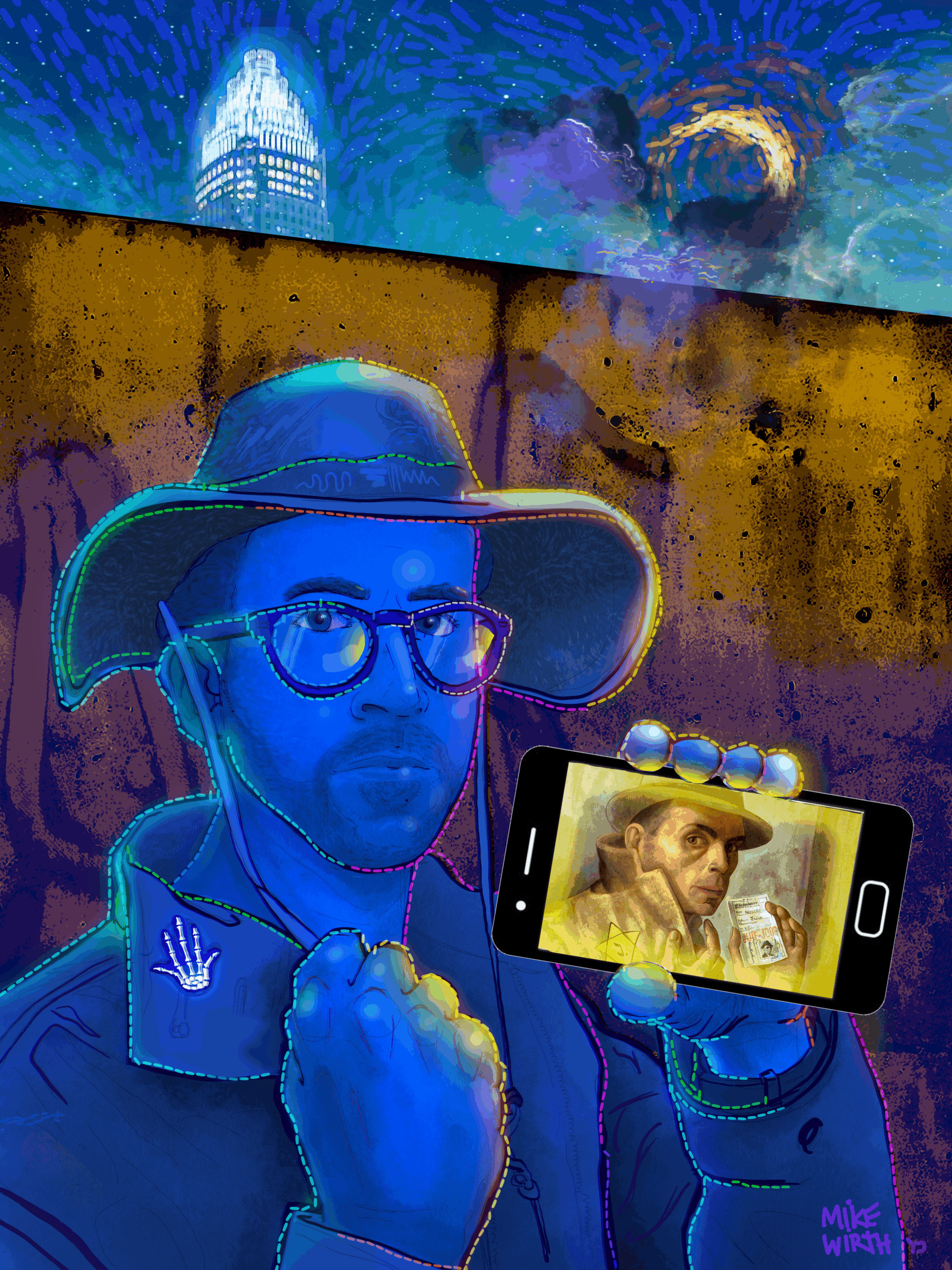

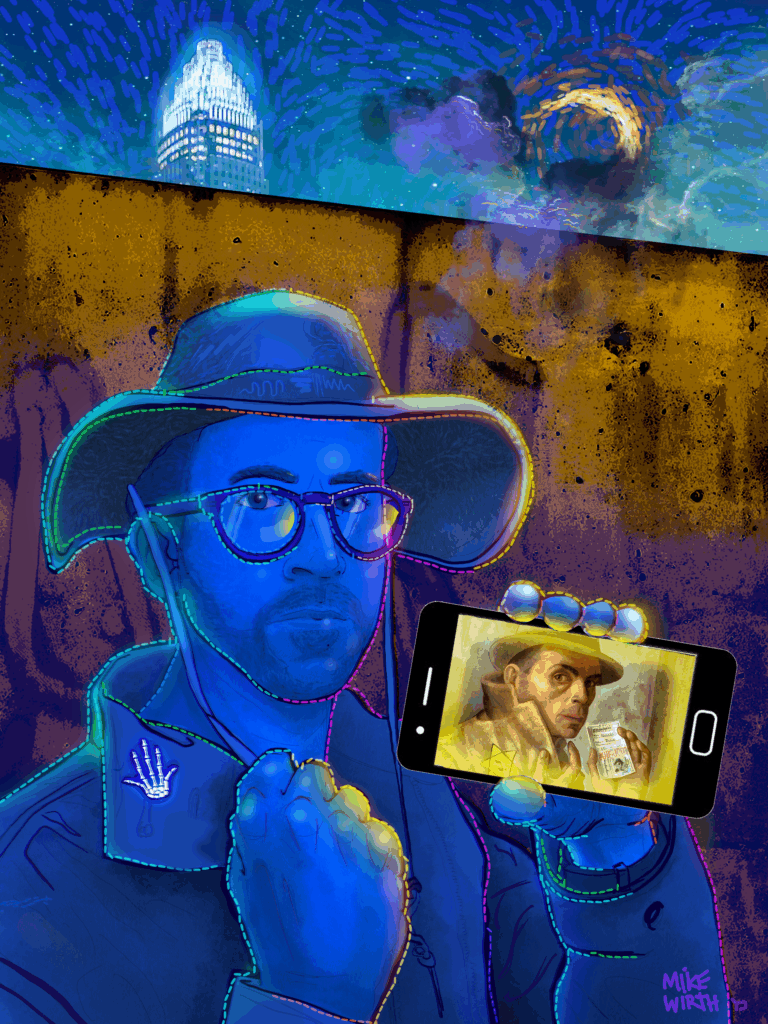

My own contemporary Jewish work was inspired by these characters. In my digital illustration piece, Silent Remembrance, I restaged a self portrait by Felix Nussbaum, a Jewish-German painter who perished in the Shoah (Holocaust).

All of our artwork is apart of a has a legacy and reaffirms the idea that beauty and sacredness can and should coexist.

The journeys of Asher Lev (page and stage), Akiva from Shtisel, Maurycy Gottlieb, Marc Chagall, and many Jewish contemporary creatives illuminate a vibrant continuum of Jewish artists who, across generations and media, confront the tension between personal inspiration and communal tradition (Morinis; Segula Magazine; YIVO Encyclopedia; SparkNotes; LitCharts; Wullschlager). Each pursues the middah of emet (truth), striving for honesty and authenticity in their creative practice, even when this honesty leads to conflict or alienation within their communities. Asher paints his deepest truths, Akiva wrestles to honor his art within the constraints of Jerusalem’s Haredi world, Gottlieb channels his longing for acceptance and identity into portraits and biblical scenes, and Chagall infuses his canvases with heartfelt reverence, mystical memory, and universal feeling (Grad; Art Prodigy Blog).

Along the way, each artist embodies anavah (humility), recognizing their role as a vessel for creativity, and rachamim (compassion), using their gifts to turn personal struggle and sorrow into works of empathy and communal connection. Their creative processes mirror the stages of Mussar: deep self-examination, engagement with inner and outer conflict, risking rejection or misunderstanding, and ultimately returning to offer artistic repair, tikkun, to their communities and to Jewish tradition itself (Morinis; Mussar Institute; Ritualwell; My Jewish Learning).

Through these acts of creative repair and ethical growth, their art becomes a conduit for goodness and revelation. Their stories remind us that Jewish artistic futurism is not static but unfolds wherever artists grapple honestly, humbly, and compassionately with the tensions of their lives. Revelation and healing do not end in moments of exile or struggle; rather, they continue through every artist who brings fresh insight and loving repair to their people.

If you’ve not read My Name is Asher Lev, watched Shtisel, or viewed Gottlieb’s work, I highly recommend all three. I’m excited to see the stage production, myself. I hope you find kindred souls in these stories, like I have.

Works Cited

- Art Prodigy Blog. “Analysis of Marc Chagall.” WordPress, 12 Feb. 2018, https://artprodigyblog.wordpress.com.

- Brandeis University. “Painting a People: Maurycy Gottlieb and Jewish Art.”

- Brooklyn Museum. “OY/YO – Brooklyn Museum.” 2024, https://www.brooklynmuseum.org.

- Chagall, Marc. Quoted in “Analysis of Marc Chagall.” Art Prodigy Blog, WordPress, 12 Feb. 2018, https://artprodigyblog.wordpress.com.

- Culture.pl. “Maurycy Gottlieb – Biography.” 13 Apr. 2018, https://culture.pl/en/artist/maurycy-gottlieb.

- Grad, Rachael. “If I create from the heart, nearly everything works; if from the head, almost nothing.” 18 Jan. 2021, https://rachaelgrad.com.

- Jewish Virtual Library. “Maurycy Gottlieb.” 2024, https://jewishvirtuallibrary.org/maurycy-gottlieb.

- LitCharts. “My Name Is Asher Lev Quotes | Explanations with Page Numbers.” LitCharts, 2024, https://www.litcharts.com.

- Los Angeles Review of Books. “The Art and Politics of Desire: On ‘Shtisel.’” 20 June 2019, https://lareviewofbooks.org.

- Lyons, Margaret. “How the Artists Behind ‘Shtisel’ Brought Akiva’s Journey to Life.” The New York Times, 20 Apr. 2021, https://www.nytimes.com.

- Mazria Katz, Marisa. “Shtisel.” 20 Feb. 2019, https://marisamazriakatz.com.

- Morinis, Alan. Everyday Holiness: The Jewish Spiritual Path of Mussar. Trumpeter, 2007.

- “My Name Is Asher Lev.” Dramatists Play Service, Inc., 2013, https://www.dramatists.com.

- “My Name Is Asher Lev.” Fountain Theatre, 2014, https://www.fountaintheatre.com.

- “My Name Is Asher Lev Tickets.” Broadway.com, 2012, https://www.broadway.com/shows/my-name-asher-lev/.

- Potok, Chaim. Goodreads Listing. https://www.goodreads.com.

- Potok, Chaim. My Name Is Asher Lev. Anchor Books, 2003.

- Rand, Archie. The 613. Blue Rider Press, 2015.

- Segula Magazine. “The Many Faces of Maurycy Gottlieb.” 18 June 2025, https://segulamag.com/en.

- Sefaria. “Introduction to Mussar.” Sefaria, 4 Oct. 2020, https://www.sefaria.org.

- SparkNotes. “My Name Is Asher Lev: Famous Quotes Explained.” SparkNotes, 2024, https://www.sparknotes.com.

- Wheaton College. “That’s What Art Is, Papa.” Wheaton College, 12 Mar. 2023, https://wheaton.edu.

- Wullschlager, Jackie. Chagall: A Biography. Knopf, 2008.

- YIVO Encyclopedia. “Gottlieb, Maurycy.” YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, https://encyclopedia.yivo.org.

- Zohar, Miriam. “Art and Faith in the Novels of Chaim Potok.” Modern Judaism, vol. 10, no. 2, 1990, pp. 145–159.