What does it mean to build a Jewish future through scissors, glue, and pixels? In this episode, I sit down with collage artist Alex Woz, who I met at the Jerusalem Biennale. We talk about the graphic design industry, swap stories about our favorite Jewish artists, and get honest about why we make what we make.

Alex grew up in an antisemitic city and turned that experience into an artistic mission. We explore the weird parallels between cutting and pasting found images and prompting AI, what makes art original, and how we’re both in conversation with Jewish creative lineage from Moritz Daniel Oppenheim to today.

This conversation goes deep on legacy: What are we leaving behind for our descendants? What does Jewish creativity look like when it refuses to disappear? And why is Alex a practitioner of Jewish futurism, even if he works with analog and digital hand tools instead of code ?

Episode Transcript:

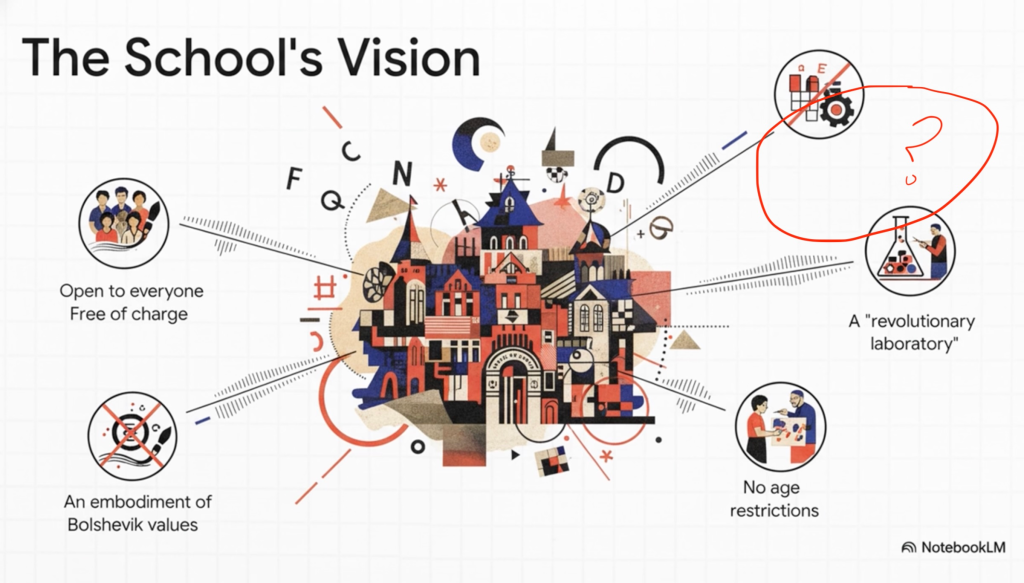

Welcome back to the Jewish futurism [music] Lab, where we unpack Torah, tech, and tomorrow. I’m Mike Wirth,Jewish futurist, community artist, and design educator, coming to you from Crowntown, Charlotte, North Carolina.Today, we’re switching gears and we’ll talk about what happens when Jewish identity meets collage, controversy, and AI with Jewish artist Alex Woz. This is the episode where Jewish futurism gets its hands dirty [music] with the messy questions about authorship, appropriation, and who gets to shape our [music] Jewish visual future. Let’s get into it, y’all.Alex W is a Jewish collage artist on a mission to empower the next generation of Jewish youth to shed harmful notions and internalize stereotypes. I first met Alex at the Jerusalem Biennale 2024 where we were both showing work and we fast found friendship in our common passions for artistry and an appreciation for the gift and responsibility it means to be a Jewish creative. Alex’s work takes found vintage photographs of Jews from around the world from the 60s,70s and 80s, people of all backgrounds, skin colors, and cultural traditions, and transforms them into a bold, empowering vision using psychedelic color palettes, and striking typography that exclaims, “We are all one civilization.” Sometimes when Alex creates, he feels the spirit of Herbert Pagani sitting on their shoulder, connecting them to a lineage of Jewish artists like MarkShagal, who have also reimagined what Jewish futures could look like. Buthere’s where it gets interesting. Alex recently shared a realization about AIgenerated imagery that sparked some intense push back from some of his followers. It’s a conversation manyartists are having right now, often behind closed doors, about what it means to create in an age of algorithms andAI. And because Alex uh works with found imagery, vintage photographs, andcopyrighted materials, this isn’t just theoretical, this is real.Alex grew up in one of the most anti-semitic cities on the West Coast. And that experience didn’t just shapehis art, it became his art. There’s something powerful about taking images of Jews from decades past. People whohave faced their own struggles and eraser and remixing them into visions that empower the next generation. It’sJewish futurism in action. Taking what was, acknowledging what is, and buildingwhat could be. So, without further ado, here’s my pre-recorded interview with Alex W. Allright, we’re here with the amazing amazing Alex W. And um Al, I want to start with your uh with your origin story, right? In a great comic book. You got to have that. Um so I knew that you grew up in one of the most anti-semitic cities um in the West Coast. And that had a lot to do with shaping your art and your identity, frankly. I was just curious if you could kind of tell us a little bit about that background.Oh, absolutely. And uh first I want to say uh thank you so much for having me on here. It’s an honor to to speak and to finally make our many conversations about Jewish art public. Um yeah, so first I’ll start off and say, you know, my um I am an Argentinian Jew. I grew up both my parents are from there. I all my families that I grew up pretty much like back and forth between here and there, like one foot there and one foot here. Um, and eventually my parents decided to settle down and fully moved to the US and we moved to um this town inCalifornia called Huntington Beach. And you know, for some people that areunfamiliar, uh, Huntington Beach is one of the neo-Nazi capitals of uh, America.And, you know, it sounds totally unexpected from this beach town in California. Um, but it’s true. They havetheir own chapter of the KKK that was founded uh there. They have, you know, tons of neo-Nazi skin head groups. And um yeah, and it’s a very non-Jewish area. Also, you know, over time, I I started to kind of critically think about those experiences. Uh you know, especially after 2020 when you know,conversations about uh social justice and social issues started to become moreprevalent. Um, I really looked back at those times and and started to realize like, hey, that really wasn’t okay. Thatwasn’t right. And it went on I went on this journey to reconnect with my Judaism. And and like like I’ve said before, I just I didn’t know I was a Jew until somebody else pointed at me and called me one, you know. Then since then everything I know about Judaism or any connection I’ve I’ve had to kind of like build for myself. Um so yeah it’s it’s definitely been a journey and I’ve heard you before talk about how uh you have such a strong connection to Herbert Pagani and uh you feel like his spirit sits on your shoulder when you’re creating. Can you talk a little bit about like your childhood experience kind of meeting that that inspirationright from Pagani and maybe how that shaped your work? The connection I’ve I’ve had with Herbert Pagani is uh can be a bit woowooand and spiritual sometimes like you said. Um I I first was exposed to him inhis work through this uh speech he gave in 1975 called uh a plea for my land.And I believe that was just following the UN declaring that Zionism is a form of racism. And he gave this amazingspeech in Paris. And uh I became enthralled with him and his character. And you know, a lot of people don’t knowthis. He wasn’t just a speaker or activist. He was also an sculptor, a painter, and a musician. And I reallyconnected with that as somebody who kind of done music for like a certain amount of time. And just the way that he hewrapped all these things up together and used them as a voice for his people, for the Jews, was very very inspiring. And Iwould collect his records. I would print out posters of him and have posters of him all over my room. Like the obsessionwas was real, you know, and um I I kind of formed this like psychic connectionwith him. And I remember when I was creating my first sets of Jewish, likevery distinctly Jewish designs, um I remember I had this thought and I wasalone in my studio and I and I thought to myself and I was debating whether or not to to share them and I was like,well, I might get cancelled if I share these proudly Jewish things. But on the otherhand, like you know, and I turned around and I see Pagani like on the on my wallpretty much like staring at me like you know the answer. You know the answer. And uh I had this thought also where I’mlike well am I an artist who’s Jewish or am I a Jewish artist? And and like thatme asking myself that question was like it made and I and again I look back atPagani and he’s looking at me so disappointed that I’m even asking that question. It’s like I felt like theweight of his staring at me and I was like no I’m a Jewish artist, you know, I’m going to I’m going to post this. Andthat just I I would say that started off this journey and this where this work has has taken me. And yeah, I Idefinitely do feel like I have a psychic connection with Pagani. It’s It’s hard to describe sometimes. I I I got really excited about Paganiagain, seeing you post so much about it. Thank you. Because I I I’ve always I’ve always beeninterested in Pagani as kind of being this more upto-date version of Rav Cook,right, with his his idea of Hebrew universalism and and his vision for the nation, right? Um you know, Rav Kook wasn’t alive then. So, uh Pagani’s spirit kind of, you know, creates that link. And then now we got you. That’s like that’s that’s a very very humbling statement. I I I don’t know. We we’ll see if I could live up to that in my life, but INo pressure. No pressure. Yeah, no pressure. [laughter]But yeah, I that’s it’s a really interesting thought to to to compare like Rav Kook’s universalism to to Pagani. And I think uh it’s a very potent um connection that you that you’re making there because Pagani advocated for the Jewish artist, not just the Jew. He ad he he he was like it’s not only I’m a Jew and I have my place on earth, but it’s it’s uh I’m aJew and I have my place in art. And and I was really excited to for for my first show. We we were able to do this likelittle documentary sort of video and um nobody caught it yet. So, I guess I’llI’ll like just say it. Um, but like uh I I made a nod to Pagani at the end there because he said, “I am a Jew and I have my place on earth.” Um, and at the end of my video, I did this kind of homageto him where I said, “I’m a Jew and I have my place in art.” Because that’s that was kind of his his whole thing,too. So, Oh, good one, Al. I’m proud of you, man. Way to go. Thank you. [laughter]Let’s talk a little bit about uh the aesthetics in your work. Clearly, you’re like this incredible collagist, but Ialso know that you paint and draw. Um, and uh I’ve read and seen that you lovechagal. So, can you talk about kind of how those things come together to form the parfait that is your style? Parfait is a good word. I am a freak for Chagal. Any anything Chagal. I I’m just obsessive. And you know, we we we couldgo into uh you know, the differences which which I’m very keen on this conversation is kind of the differences between Jewish art, the cannon of Jewish art and non-Jewish art in in art history. And I I think that there issuch thing as Jewish art. And it’s doesn’t mean it was just created by a Jew. It’s actually a way in which theJewish experience is is uniquely channeled visually. And I think no, there’s no artist alive or dead who everdid that as well as Shagal did and and channelneled that abstract whimsicalitythat’s part of the Jewish spirit um as well as Chagal did. And you know therethere’s this rule I always I I have it hung up in my studio. It’s like you andthis is mostly about writing but it applies to any art I think is like you you show the viewer something. You don’ttell them something. Um, and and Chagal was a master of that. I think one of mymy favorite paintings of all time, I’m sure it’s it’s called the crucifixion or the crucifix. It’s a Chagal painting ofof Jesus in being crucified in Eastern European while it’s on fire and he’swearing a talent to fill in on the cross, which you know nowadays you could say, okay, so what? But back then, likethis was like very inflammatory and very provocative in the art world. an art world that you know kind of shunned Jewsout until maybe what 20 years before Shagal even came on the scene. So it’slike very fresh, you know, and he he’s using his art to just tell the viewer, hey, he’s telling Europeans, hey, ifyou’re Christian, it’s maybe a bit hypocritical to go burn down a Jewish stle. And he’s he didn’t say a word tocommunicate that. Not a single word, just just visuals. And and in that way,I think he’s kind of the the rockstar Jewish artist. He’s he’s the tip of thepeak, you know. Yeah. Shagal Shagal really was for me one of the first Jewish futurists in themodern space if you want to call it that. um you know he and Lzitzki formed the people’s school ink right sohe had he had returned to what’s now Bellarus right the vetleright and um you know with help from the government was able to be the chancellor of this school right so we we alwaystalk about like bow house and uh you know the the verakund and the other likeuh European design schools you know that were uh liberal and groundbreaking thatShagal and and Lzitzki really were with um Kasmmer Maovvich who wasn’t Jewish,right? They were the founders of the UNovese, right? That that first avantgard uhschool, right, in that space, right? And and you know with the founding of the school, I think likepersonally what why I love Shagal so much is is not it doesn’t only come downto his style. It comes down to ethos and the philosophies that he was using his art in which to promote. Like forexample, what he did essentially was craft this unique visual language and that he used that visual language tobuild a sense of cohesion and connection within his community. Of course, he started like you’re saying these schoolsuh or the school, you know, to kind of connect all these artists, not only Jewish, but a lot of those pioneers wereJews that would attend that school and and do studies. He did the the famous Jerusalem windows. He did the the muralsin the Yiddesh Theater. So like people knew him. There there’s kind of this like saying in Spanish which is likeyou’re which means like you’re you’re a man of the villageand he in many ways was like a man of the village in terms of he representedthe people um with his artwork. you know, even if he didn’t come out and say that, like that’s what he did. And Ithink that philosophy is what I tried to take most inspiration from. Not necessarily copying his style, per se,but um that philosophy of like he created environments for other Jewishartists. He created a platform for other Jews that all uplifted each other through studying, through collaboration,through work. And that’s the most inspiring thing. Man, it’s so nice to hear how how you take from one of ourour great ancestors, right? Creative ancestors. I’ve always been excited about Chagal because he’s a what I calla mystical futurist in that he reveals like the liinal uhsupernatural world as being this place um that uh you know, Hashem dwells andJews dwell. Um and then you have Lzitzki, right, who is the technofuturist, right, who is all aboutprune, you know, the um the geometric stuff and the suprematism of ofgeometry. So I always felt like the two of them were two sides of the coin. I’ve always just saw those two genres as likea a cool way to look at futurism. You don’t have to have circuits to be futuristic or technology. you you can bemystical and spiritual and take us to a hidden place. That that’s kind of what we were sayingearlier about the the differences uh like you just touched upon what what I would consider to be one of the keydifferences or or I would say maybe assets that the Jew has uh when creatingart that makes art distinctly Jewish is that you know and I will speak a little poetically but like I think being Jewishsometimes feels like you’re frozen in time. you’re you’re you’re part of this collective that’s uh older than a lot oflike modern groups of people or even modern ethnicities. Like you’re you’rejust this sometimes it feels like you’re this ancient person walking around but at the same time like we take that andwe use it to create new things and we exist in this kind of limbo of time. Ifeel like is an artist that captured what that feels like so perfectly. likeyou you look at his work and it’s not about perspective. It’s not about um technical skill even though he was verytechnically skilled. It’s about that third space that mental liinal spiritualplace that Jews inhabit. You know, I get that idea of being frozen and I’ I’velearned to see things more as like a cycle of like cyclical time, you know, like we take Shabbat and we we go allthe way back to history and we bring it back to now, right? And we even go into the future talking about the world tocome, right? Uh olam hatikun after we’ve repaired it. So I just Iappreciated in your pieces how, you know, you’re bringing in all these different kinds of Jews from around theworld and through time who kind of possess different mystical qualities. You know, I I look at thatand I see, wow, like that those individuals are I feel like they’re more mystical than I’ll ever be. Talk aboutthat. how how when you where you’re getting these resources from and then you know what what draws you to acertain image you know takes it to the uh the wonderful place of a piece.Absolutely. Um well first I’ll say you know how I first started with this is umI I was doing design for the music industry for like a number of years upto that point and this is probably 2021. Wow. just doing merch packages and showposters and and album covers and things like that. That’s kind of the design that I had cut my teeth on. And likethat’s why when I first made those Jewish pieces, the the the very real threat was like I’m about to lose myjobs, you know? I’m about to lose all my commissions. I’m about to like if I come out and be proudly Jewish in my work, umI will lose things. I will lose connections and commissions and people. But at that time I had this was 2021there was an operation called operation knife edge in Israel in which produced this like shortlived war between Israeland Hamas and during that time social media like really really exploded withanti-Israel propaganda and sentiment and everybody has their own experience for alot of people it was October 7th but this was my first experience seeing my progressive liberal friends sharinganti-semitic things I grew up with Nazi anti-semitism, with skin heads. So, itwas like a huge punch in the gut for me for my progressive friends, the ones that I thought would be the mostempathetic um that were now sharing this stuff. That was my first experience. So,I already by October 7th, I had already cleaned the house of all of those people, you know, that would be postingthat. They were were already cut off. Um but during that time, I would start to see the classic liel. Israelis are whitecolonizers. And I would say hm, you know, even though I kind of like look like Larry David, like I’m actuallySephardic, like I’m I’m the lightest person in I’m like the light token lightkinn of my family. So likeI you know, I knew that wasn’t the case just by my family photos. And so, youknow, my dad had given me this book called Portraits of Israel, one of those like classic 60s thrift store books.And I and I went and I opened it and like the whole Israelis or white colonizers thing would have disappearedin in two seconds just to open that book. So what I did was I took scissorsand I just started cutting out the Jews in the book and uh I think I cut out like a Bkarian Jew, Ethiopian Jews, andsome some Jews from the old Yeshu. I just started making art with them. And for the one with the Bkarian Jew, Iactually I took the pattern of a Jude star from the Holocaust. And I printedit, res-canned it, and then like moved it around the scanner and basically duplicated it to make this like fabricbackground out of the Jude star. And then I put the Bkarian Jew on top ofthat. you know, these I found that these photos and and now like I I got intothis groove of working with these photos where I’ve basically destroyed all of mymost cherished books. Oh no, [laughter] all of the juice out of them andscanning them. But besides that, there’s this process when you when you find the photo of like and this took me years toto get to the point of like maturing a little bit about the impact of these things. is like now I look at the Jewsthat I use in the work and I’m like I have to be kind of precise because I’m using somebody’s likeness in this worklike a real person that existed. I need to do them justice. Uh I can’t put themover like some you know statement that they would disagree with or some piece that they would you know not feel likerepresents them. So it kind of adds this extra pressure for that. I kind of like I do this like very hippie-ish uh thingwhere where I look at the photos and I kind of like meditate on it for a second and I’m like what do you wish you couldhave said in your life like if you were alive now what what would you want to say like how can I respect you you knowand I kind of have that psychic conversation with with it and then Ikind of move accordingly from there and hey have I hit the target every time of course not I have had uh impactfulexperiences Like I did this one piece and posted it of these Yemenite Jews inIsrael and it was for something for Tishvat. Somebody DM’d me and was like, “Hey, that’s like literally my grandma.”Like, oh. And they’re like have been so stoked to see that and I love it. And Ishowed my mom and we’re printing it out and I and I sent this whole family with some like really nice prints with a nicenote and was like, “Thank you for letting me use the photo of your grandma.” [laughter] Oh man, that’s so cool. Yeah. Right.Thank you. Right. Gotta be careful, you know. Yeah.Yeah. Oh man, that’s Wow. That’s incredible. Like that that’s exactly what we’re talking about. This kind oftime loop, right? like those, you know, somebody took that picture, you know, it went in that book, who cares? And thenhere it is again, and it means something so much more than it ever did, right? Like that’s that’s amazing. That’s awonderful example of Jewish futurism, Alex. Way to go. [laughter]Let me ask you a serious question here. Right. So, you found this in this book and you’ve now you now appropriated theimage, right, into your work. Sure. So part of us talking today is I saw online that you had put that youknow you had a new new thoughts and new feelings about AI and AI work and youknow one of the big concerns with AI art is that it’s data sets are trained onimages of copyrighted imagery right um so t talk to me how are youapproaching the use of appropriated imagery and fonts and things like that to to then repackage and then we canmaybe float into AI. Mhm. When I was younger in in in mydesign journey, and I’ll just say this like for context, my whole life I was doing more drawing, life drawing wasactually my was going to be my major. And studying painting and that sort ofthing. And then started college earlier. Um, and when I was 16, I was doing thispainting class with this amazing mentor, Kim Garrison. And she’s this incredibleMandela comic book artist and she was just one of my biggest inspirations. I would always stay after class and just,you know, chat with her. And and one day she she told me, she’s like, “What’s your major?” I was like, “Oh, it’s like life drawing and that sort of thing.”And she like frowned and she was like, “You don’t do that.” It’s like, “Why?” And she’s like, “Because you don’t needa degree to be a good visual artist.” She was like, “Why don’t you get your degree and learn how to do a differenttrade that is more uh capitalistic, so to speak, that you can like see a aproper career in? So, why don’t you learn how to do computer design and graphic design?” And I I was 16 at thetime, and I was like, “No, think about it.” I took a few classes and then I fell in love. And probably I would sayalmost every day I’m I’m was designing. It was it just became like an obsession. Um, andthat’s prolific, man. I mean, it’s like I I just hit the 300thpost mark on on my Instagram, and man, I’m just thinking like out of that 300,there’s got to be 20,000. I mean, that’s a hyperbole, but you know what I mean. Just a lot a lot um that were just badand practice. And that’s what it takes. I I I really believe in uh quantity over quality. Yeah. with design with withyour question. Sorry for the little tangent. Um when it comes to appropriation when I was younger in mydesign uh journey, I would say it was so much uh that line was a lot more blurryfor me. Like before I developed a visual style, I would like look at other visual styles and try to emulate them, which Ithink is like pretty normal for for young artists trying to find their voice and their style. And a lot of the timesI would emulate them really closely or I would appropriate elements without changing them. And um I I even look backat some of my old older art and I’m like man I did not um push that to be asunique as it could have been. Um but you know that’s how you learn. Like I think if I looked back at my oldart and I was like proud of it there would be something wrong. [laughter] Right.Um, but you know, and I’ll I’ll refer to music, you know, with with the art oflike, let’s say, sampling records out. Uh, that was like this conversation washuge, let’s say, in like the hip-hop community. Um, people making hip-hoplike they were just putting up songs of sampling and of course the in samplingthem. And of course, the question was like, at what point is it an original song? And you know what? I think thatyou there’s it’s almost futile to like really dissect dissect this because you knowice ice baby and under pressure you know [laughter]right you know you know and sometimes when you when it’s taken on this different formespecially in design like using elements as part of something else I think it’s fine that’s like sampling a songproperly uh fully taking something and then saying I did this and then adding very minuscule things without making itclear that it’s a reference. I would say that that’s uh something that nowadays I try to avoid but it’s a trap that I fellinto when I was a younger designer and I think a lot of designers do. Yeah. I that’s why I wanted to ask youbecause I think you know the idea of originality, right? And like what it means to like what qualifies as acrafted artwork um you know it gets back to our conversation before about what is creativity and art versus design and andthe the fluctuations between that space. I feel like uh AI art or using AI tomake art um is akin to collage making because there’s appropriation in it,right? Um and I I know it’s not the same. I akin is a very flexible word.Um so when I and here here’s where I’m at with it, right? Is I’ve gotten to aplace where, you know, I could look at collage and be like, well, I could make that, right? Um, why is that a milliondollar? Why is that Jasper John’s, you know, a million dollars, you know? Um,he glued paper to paper, you know, like it’s not even his own art, you know, like like you can sit there and and playthat that rationalization game. Sure. But then it’s like, all right, cool. But once you get past that and you kind ofrealize that’s not what it’s about, you’re like, damn, this is saying a lot to me. And you kind of like let it letit wash over you like jazz. Right. Sure. And um I I I’m starting to getthere with AI art and a lot of it has to do with like a lot of the AI artistslike like this like so people who want to be creative like um like one of thegreatest uh duos to ever get together is Mark Podwell and Ellie Visel.Oh man, that’s magic right there. Magic. Yeah. Right. And it’s like or or when you seeum artists work with rabbis, right? or and come together and like make some crazy awesome stuff like they do onSafaria, right? Oh yeah. Uhhuh. So the way I look at it is like collage democratized things just like uh AI hasdemocratized making, right? Image making and um so if uh now all of a sudden arabbi or or somebody who has these great thoughts can make these images and craft them the way they wantto have that communication with us. Mhm. You know, that’s what I’m talking about. That’s the stuff I’m like, “Wow.” Youknow, I never thought about that. That’s brilliant. And um we wouldn’t have everknown it because that person would have felt blocked or or excluded from the ability to make art or or they wouldhave had to have done something very difficult to get there or collaborate, right? like and you can’t always there’snot always a Mark Podwell in your neighborhood to react to that or what are your thoughts kind of on that whereAI can be a tool right that like can be akin to collage? I would say I I agree with points there.Um but I would say as a whole I I I would lean more towards disagreeing. Umbecause I think the key is kind of in that last point that you just made there which is AI is a tool. And if AI is atool, then I I would say that automatically nullifies the the idea of collaborating. Um because, you know,when you use a hammer to hammer in a nail, you’re not collaborating with the hammer to to hit the nail. You’re usingthe hammer um to do what you want to do with it. You know, when you’re using AI as a tool, you’re using it as a tool.You’re not treating it as a separate entity that, you know, whatever its input is is valid. And that’s kind of,you know, has you can can dive into kind of the quickness of how it creates things or how it actually samples otherart to um to create things. And you know, that’s a very very interesting topic of exploration, which is how AIsamples other art in in kind of this library, this database versus like humans kind of do that same thing forourselves. I think AI has pushed us to kind of differentiate between art and animage. And trust me, I always say this to to to anytime um any one of my artsyfartsy friends wants to have this conver uh like a conversation about what is art, I’m like, “Oh, can we move on?”Like, I hate that conversation. What is art? Um but I think because I think it’sa pointless conversation and you never get anywhere with it. Um, but I do thinkAI kind of like rebirth that conversation and kind of breathed some new life into it because and here’swhere I would draw the distinction to the point I’m making is that AI is creating images. It’s not creating art.And I would say that the thing that makes it art is the the the human uh thehuman element to it. So if a rabbi for example wants to create images to toconnect uh viewers to his teachings then he could use AI and create an image. ButI would say that by mere merit of the process alone it’s not uh I would sayI’d be very very uh hesitant to to uh call that art and to to to go along withthat as art. So, I guess I’m curious like if an AI model was to like train onAlex W’s art and then like it could generate your stuff all day.How does that feel to you? Right. How do you feel about like that? You you think that that’s uh and and let’s sayyou had access to it like it wasn’t like someone cloned you and put it out on the internet, right? Went crazy.Let’s not get that paranoid yet, right? What if you I went through an experimentlike this with myself, so I’m curious to ask like other artists like how would you feel about that? You know, if you were to make a an Alex W AI imagegenerator that could work with you, right? Or you could use it as a tool, like a sketchtool, right? What do you think? First, uh you know what’s funny is that this actually happened to me. [laughter]Yeah. Tell me. Tell me. So, you know, without uh being uh naming names or orof course not, definitely don’t want to shame anybody, but like uh there was this page on Instagram that was postinglike things that were very very similar to to my style and but you can tell that it’s AI, you know.And um this uh person actually ended up reaching out to me because enough people sent it to me and they were like, “Whatis this?” you know, other people caught on that it kind of like looked a lot like my work. The person actuallymessaged me and she was like, “Hey, I hope you don’t mind, but I fed your artto like this AI is like something like that and I’m asking it to to create meimages for my profile using your visual language.” And uh man, I had to like gofor a walk after that. Like I had to really think about how I feltabout that one because like Yeah. Man, I I went through a lot of different emotions from like flattery tosaltiness. I’m not even gonna lie. I was like, that’s kind of weird. And and of course, I I I was nothing buta gentleman to her. I was like, hey, just like very politely ask you to stopdoing that. [laughter] Yeah. So, so I, you know, and even to this day, that was like a year ago, buteven to this day, I’m still like, um, I would say in in the case of yourquestion specifically, you know, if I if I was working with it and using as a tool, I wouldn’t mind. I mean, I thinksometimes like for certain commissions that I have where it, you know, I’m creating something for somebody elsethat requires this like high design IQ. Um sometimes I will go to chat GPT andtype in the concept and say hey I’m working within these parameters within this concept. Can you generate me anidea of how to combine these two things and it will generate me an idea and I’ll work accordingly. But then of courselike I’ll create everything from there. It’s just kind of generating the idea. So I guess that is maybe the closestthing to to what you’re saying. Um, but I I guess it would force me to if there was like an like an an AI that couldjust like pump out my work. I guess it would it would force me to kind of likeuh innovate my work in a way. It would force me to like seek out new avenues. And I guess it’s it’s already doingthat. But um I would have to level up. This kind of where I’m going is like uh you’ve already listed ideiation as as anethical use for AI, right? As you’re you’re describing it now.What else? What else do you think could be ethical uses for the technology? Because I think you and I both agree wedon’t want to use this in our final work. Right. Because that that that crosses the line just like you know yourfeelings about that that sounds like a lovely person who is probably more flattered than than malicious.Right. Exactly. And and that’s you know that’s what what the vibe I I sort of got from that. I I I think that keepingit within the boundary of a of a tool I is like of utmost important if you wantto kind of retain some level of like a feeling of ownership over your work. Iwould say maybe um I I just think like for example do use AI as a tool everytime I create in the sense that when I’m designing I’m using Photoshop and Photoshop has tons of plugins and toolsthat actually use AI technology to kind of work them. One of them is called generative fill and and maybe forsomebody who’s listening doesn’t know what generative fill is. It’s this uh this Photoshop action that let’s say youhave an image of like a sky in the beach and you say I need this image to be 1inch larger to the right. You use generative AI and it will use AI to kind of guess the context of what’s missingin that extra inch you’re looking for and it will generate the rest of the beach and the rest of the sky. I usethat all the time in my work. You know, when I’m working with old photos and I need to punch them up, I need to dosomething with them, but it’s always my hand and my mind that’s guiding it. It’s like very much using it as intended,which is a tool. I think there’s definitely a very clear line where you’re using AI and you’re relying on ittoo much and the human hand becomes invisible in your work and and I think every artist should try to avoid that.if you your process involves uh anything digital, you you shouldn’t you have toknow where that line is for you. I’m glad you brought up Adobe because they’re one of the few AI where theyonly train their uh data on their Adobe image library, right? So, it’s alllegit. And I think that’s a huge thing is that the technology got rolled out using the whatever it’s called the lindata lion database that’s like trained on the internet and they just drove that that truck into the ditch, you know,like straight away, right? I’m glad to hear because I I saw on your uh on your Instagram story, you know,that you were having a some thoughts about this. I’m I’m glad we’re unpacking that. And then someone chimed in andsaid like almost defeated like like they were so crestfallen they were like not you Alex. Right. [laughter]So what would you respond to that that thought with? First I’ll say um you know in in thatvideo I I was speaking on AI and w with a with a tinge of optimism in terms ofwhat it can actually introduce into the our current art culture and space. Andmy idea was that, you know, AI is going to turn uh create a renaissance in the arts. And um as soon as I said that, Ihad somebody message me, I can’t believe you’re defending AI and art. And I was like, did you even watch the full videofor [laughter] the the I think they heard me say something that’s not like so defeist andpessimistic about AI. And they immediately like some bell went off in their head, which I get it. if theywould have, you know, maybe watched the the rest of the video, um, they would see that the point I was trying to makeis that what AI is doing is it’s almost it’s saturating art so much that it’sforcing us, not just inspiring us to do this, but forcing us uh to kind ofrecontextualize the reasons that we consume art to begin with. AI, and this goes back to kind of what we were sayingearlier, I do think that there’s a difference. AI created this difference between what is an image and what isart. Um, and I think what AI does is it creates images. But I think if you want to have that, you know, fofyconversation about what is art in this context, it means that it was guided by a human hand and a human mind. My pointis that what it’s introducing is that people now will look at images and realize recontextualize why they want toconsume them. And and for example, they they might look at an AI image that that’s very artistic. Uh they mightthink, hey, like why do I even like to look at art to begin with? uh is it to look at a final image or is it actuallyto connect with an artist, their process, their character, their history, and the human connection that I can kindof feel and like what we were saying earlier like I felt this spiritual connection to Pagani because I’m such anerd for him in his character and his life that I kind of formed this parasocial relationship to a dead man.That is pure magic right there. That’s something that only art can make you do. I don’t see anything like that happeningin AI and I see AI pushing people to say okay you know what in in where can I get that I’m going to go to a gallery. It’sthe same thing with music. If if an AI can just create this this amazing songit makes you think why why do I even like listen to music? Is it just to listen to the final song or do like Iactually want to consume also uh you know this musician’s like story, theirbackground, their this and their that. And um I think AI is really helping usto realize you can’t divorce those things. It it’s actually like the biggest reason of why we consume art isis to do that. And I I kind of predict this renaissance of these artists coming out in in in creating these new thingsthat are focused on the human imperfection of the hand. That is and I say this all the time. It’s creating this recession for skill-based artworkand creating this uh incredible demand for for very humanistic artwork that emphasizes human connection. somethingthat only an artist can do. My last thought on that is that the development I’m most excited about is that it’sre-emphasizing and recreating the the birth of the character artist. And andwhat the character artist is is the Basad, the Warhol, the Pagani, theShagals, the artists that were so ethereal in their character that they were like mythical. And you can’t haveBosiat’s work stand alone without understanding him as a person or hisstory. But I see like tons of clones of Basat pop up on my Instagram sometimesand I’m like, man, you don’t get it. You can’t clone Bascad. Especially, right? You know, you’re missing the the theexperience that made his work his work. Like, I’m sorry, but you can’t copy Basad. And I’m not saying because I’mthe police, art police, but like you’re missing the whole point of his work to begin with. It’s not just about thefinal image. It’s about his experience um that is unique to him. You know, now with AI, people are craving that again.And for a long time that character artist has been dead because we as artists have been told in the age ofsocial media, you have to share as much as possible. You have to create videos of your artwork. You need to like almostbe a content creator. Now, I think people are starting to crave a level of mystique from artists again and andthey’re craving that sort of mythical character to be an artist again um that we’ve had missing for so long. So, mytheory is that one, the character artists will be reborn. And two, we’re going to see a big shift in terms of anartist will be praised not for how much they share, but for how about theirpersonal lives, but for how little they share about it because it’s they’re they’re creating that that mythicalcharacter. I’m sitting here and I’m kind of thinking about we’ve had the Banksies, the uh Shepherd Fairies, so to speak,you know, that have like kind of emerged as a you know, artist personality, you know, and Banksy hid himself. ShepherdFairy’s out and about, but he, you know, he’s gone to jail because of it, right? I think AI is is hyper amplifying likewhat you’re saying. I agree with what you’re saying about content is going to be so saturated, right?But content and art are different like you said, right? Absolutely.So, I I think people don’t get that and they conflate the terms and it’s like we’re not even having the sameconversation at that point. I remember being in Miami for Basil in like 20192020 seeing um an artist and we won’t name names right but seeing an artist who was just spray painting charactersfrom like famous board games and I I just was likeokay like sure I I I’m I’m with appropriation you know like I I I appreciate pastiche you knowwhen uh and and homage and things like that and when people do that like with real good accuracy and with a story totell. You know, this is this is preAI, so like I’m I’m seeing this stuff and I’m just like, “All right, where are we going?”Right? What what is happening here? And it it I remember thinking all right you knowlike that person can be successful and fine and and it it is it’s like I thinksocial media created this like where content rose above art and um we likelost the battle a little bit. Right. I So I want to then jump on what you’resaying also I think is great is that AI is going to exacerbate that because now the people who are content creators aregoing well I don’t need art anymore. Like we don’t we can divorce oursel from that worldyou know so to speak. So I feel like there’s going to be a little bit of an agency uh of of realms. So like maybethe art world will go in a different way. Um or maybe uh folks will come in and crashit. May we may have our first kind of AI artist who’s famous, you know, who wholike does something that makes us all think and pushes it and we’re like, oh,you know, so like I I have a little a bit of an optimistic feeling about that.It took me a long time in my career doing art and and kind of stepping intothat identity as an artist to to be able to acknowledge that there is such thing as bad art. At least to acknowledge likein my opinion I think that this is bad. like you you kind of go through this like art school circuit where you’relike trained you’re like hyper trained and conditioned to like you know intellectualize every art piece and likelike overrationalize or analyze things and to try to see the value in them which I think is good but at the sametime like you kind of like pass that bell curve and you’re like back where you started where you’re like no like some art isn’t good and it’s okay tojust like say that. Um, but I I’m not crashing on on anybody doing that, but Ialways have this meme with some of my artist friends where I’m always like, “Guys, if I was president for a day, Iwould make it illegal to ever paint Marilyn Monroe ever again.” Like,like, if I was president, no more painting Marilyn Monroe. No more painting like Dollars on Fire or like[laughter] Guys, I think it’s been done. Um, but I I’m just joking. I’m I’m just jokingabout that for anybody who’s painting amazing Marilyn Monro [laughter] piece.Um but but please say something new about Marilyn or with Maryland we haven’t heard yet. Thatexactly and I will say you know I do if if there’s any art movement that I dofeel a bit more comfortable to throw a little challenge at or to throw a little bit shade at. It’s that like very verycapitalistic art that’s like very clearly made to sit in a rich person’s mansion. you know, it’s kind of likethe point of it is that it’s kind of like sterilized from this this aura like and it’s just about characters andthings like that. I have no problem to just acknowledge at least publicly to say, “Hey, um that that kind of stuffdoesn’t do it for me.” But I do think that you’re on to something really interesting when you say there will bean artist who use AI in that way in that preference was important because I’m about to kind of like double down on onwhat I was saying is in say maybe a controversial statement um which I will by all means accept push back for but Iwill stand on this. Uh I think there are certain art movements that can only be done once in in by one person or or avery select group of people uh successfully so to speak. Again, not the art police. You do whatever you want todo, but I just mean in terms of it’s like really adding to the conversation at a certain point. For example, I wouldsay Jackson Pollock with drip painting. Jackson Pollock really did revolutionizeand his, you know, partner which he kind of uh Lee Kraner, right? Yeah. Like, you know, kind ofappropriated a lot of that works and techniques from regardless, we’ll just say Jackson Pollock. That drip paintingwas was virtually unseen before then. And and you know, I’m not I would never insinuate that to to do drip paintingdoesn’t take skill. Of course it does. It takes immense compositional and color theory skill. But as an art movement, itarrived on the scene kind of to spark that conversation. And it did have that conversation. And now I feel like weexist in this postpolloc world where all of the conversations that could have happened about drip painting havealready been had, so to speak. We’ve had almost every conversationthere is to have about what drip painting introduces into the art world, the way it changed how we think and andso the functionality so on and so forth. Um, and the reason I bring that up isbecause I would think um, but I would say that I do think that this artist that you speak of, this like uh,hypothetical future artist that will use AI in a way that will spark conversation about, you know, AI and art that issomething that in my opinion can only happen once there. I think there does need to be that artist and he’s probablyor he or she’s probably out there right now, you know, like uh, this is probably brewing as we speak. Uh, which I’mexcited to see. I really am. Uh, but I do think that that’s one of thoseconversations that maybe has a has a shelf life for how often it can be uhrepeated, especially especially with AI. Really not controversial at all, Alex. Ithink, you know, I think our uh our AB ABX uh compatriots and colleagues, you know,they they get it. That’s that that was lightning in a bottle, you know. So there may be that too in the futurewhere somebody could come along and bring drip painting, action painting, right? I think it’s called into the next. Let’s talk a little bit about thefuture for a second. Can you talk a little bit about like when you make your work and you put it out there, you know,and this generation is consuming that, right? like Alex, you’re a household name when it comes to Jewish art and uhI think man you you made the jump from mainstream pop artists to amazing Jewishartists at the perfect time. Seriously, what are you setting us up for? Right? Like when you show this generation allthose images, right? Even my generation, right? I’m 46, Gen X, right? So like I too wasn’t exposed to those things um tobe, you know, and and now appreciate. When you’re remixing the the past with the now, where’s that going? Yeah.What’s your intention? You know, what do you want to see us do and and be? That’s that’s a great question. Um Ithink kind of to to that very very kind and very gracious first points that you were making. I I think that philosophythat has kind of guided uh me to even create this work is actually the same philosophy that is still sustaining meevery step. It’s it’s this thought which actually my brother told me when I was a lot younger and that’s if you want tosee something if you wish that something existed that is your sign to go do ityourself and to make it yourself. I think that’s why I started to do Druid because I was so involved in the designspace. I mean like I said I was doing two three designs every day since I was 16. That’s like 11 years of of just likeobsessively designing and like I think during that time I got so absorbed inthe design community uh which is amazing by the way as you know and then like weexist at the junction of like Jewish community and design community which is like in that space I had always wishedthat there was a designer that was like proudly showcasing Jewish things andwhenever like during maybe when I was 17, 18, I would like still look forJewish things in design, but I was like really hardressed to find them outside of certain contexts. Like for example,one of my design heroes, Dan Risinger, and and Dan Risinger, who pretty muchdesigned the visual language of modern day Israel, like back in the 70s, like that that’s like that’s like still oldthough. And that’s in the context of Israel where like everything’s Jewish. It’s not like uh it’s not exactlygroundbreaking to to make like a to put a Star of David on a piece of design work that you’re doing in Israel. Umstill amazing and I love it, but the the kind of provoc uh provocation is not thesame. Um, and I and I kind of wish that out here, at least in this the secularworld or in the diaspora or the west, whatever you want to call it, that there was artists that were willing to to dothat also in in in a foreign context, so to speak. And and again, let me clarify,I’m not diminishing Dan’s amazing work. He’s he’s one of my heroes, one of my idols. I realized, you know, in and thisgoes back to when I first made those designs and I hesitated to share them because I thought, hey, if I sharethese, I’m going to be opening myself up for to get cancelled and to lose all mycommissions, to lose all my clients, to lose all my jobs, and to kind of to become a pariah in the design community.And you know what? That’s exactly what happened. Uh when I first posted those designs, I I sat back and I waited andthen I and then the calls came in, the texts came in. I had like two, three clients that dropped me immediately. Butyou know what? The the response was actually like 300 times greater than anyof that. It was actually Jews coming out of the woodwork and, you know, coming and and commenting on those pieces andand sending me message of like, hey man, it’s so nice to actually see Jews being represented in a positive way. Big fanof design and I’ve never seen Jews represented positively in design. And then that that kind of led me down thisroad of like, hey, that’s my case, too. I’ve never seen Jews represented positively in the design. And then thatadded this layer of like tikun onto my work of like, hey, I need to do this. I had already lost all my followers by thetime I started posting more Jewish things, but I gained back like 10 times as much of followers who were alignedwith me. And you know, if you know me personally, you know, I never care about followers. I never like really soagainst the online cloud thing and I always was. But in terms of people who who genuinely felt supportive andconnected to the work, that is priceless. I think the the work started to build this new purpose that was somuch so much greater than myself and it still is. Somebody has to do it. There has to be an artist and this isnon-negotiable. There has to be an artist. There has to be a designer. There has to be a musician, rapper,anything that is Jewish that puts that first and allows themselves to be made apariah because of that. And I feel like that’s exactly kind of the role that I stepped into, at least in my niche,which is design, to be able to open myself up to to that criticism and inlosing all my clients and losing my what essentially was my old career to to to stand on on the message of this work,which is like, hey, nobody will respect you in your industry. It doesn’t matter what it is. Especially in creativeindustries, if you don’t respect yourself, especially as Jews, they willtrample you and eat you alive if you don’t know who you are. If you’re not a strong Jew, and I don’t mean that assome flowery words that mean nothing. Oh, just be strong. No, I’m not saying like if you’re a creative, you knowexactly what I mean. And so what I really want to do is to just like be apart of a movement of Jewish artists like yourself, Jewish designers, Jewish creatives that say, “No, being a Jew isan integral part of my brain and my creative process and my soul and my expression.” And I’m not going to dilutethat. And even if it makes me a pariah, even if I lose all my contracts, all my clients, it doesn’t matter. I’m going tobe still standing here firm. I think today in the creative industry, we have like less than 5% of us are doing that.So proud of the the Jewish artists like yourself and like so many of these other artists I see, colleagues,contemporaries, peers that made that same jump themselves. In a way they saylike leap in the net will appear like yeah you know you could say a lot about the Jewish online community or theJewish community in general with being divided but like when push comes to shove like they will catch you likereally strong in a way that no other has like that um cohesion is so strong whenit’s needed. When I needed it it was there for me. So I guess all I want to say into, hey, if I can make myself apariah, if I could lose all of this in order to just put this message first and foremost, like you can too. And ifenough of us do that, they can’t like cancel all of us. And if they do cancel all of us, then we’ll then we’ll do whatwe always did and we’ll create another Hollywood. We’ll create another like, you know, diamond diamond like creativeexpression industry that is like in some way just unique to us that was born out of our marginalization. Okay, they canmar they can marginalize all of us and watch the soul suck out of on the creative industries. That’s that’s theirprerogative. If they don’t accept us, if they don’t accept the Jews and the art world, then they will struggle with ourabsence. You know, what would you what would you say that like you want there to be for young Jewish artists that likeyou have control over that you know you can put into the art world? whether it be an opportunity or realization orexample, you know, what is it that you, you know, your legacy as as a human? I I’ll I’ll speak firstlike first as a human and then as a as an artist, I as speak like as a human, II want to have kids. I I want to have a family. I I want to be able to look back and just put that first and say I was akind person to others and I was able to make them feel seen and heard and loved and respected. that that is alwaysfirst. As an artist, I’m not I’m not going to lie, like a lot of my older work that is more like about that Jewishexperience, it touches on anti-semitism. Um, I want all of that to be irrelevant.Like, and I know that that’s like a big ask. You know, it’s maybe hopeful thinking, but in my ideal world, like Iwould look back and there would not be a need for art like that to be made. artthat’s like provocative about the Jewish experience and pushing back. And you know, in an ideal world, there would beno need to push for Jewish representation because we would already be represented positively. Butunfortunately, I don’t think that that’s where we’re heading like [laughter] a light. So, let me like step down from myuh your soap box for a sec. Yeah. My good. It’s a good soap box.[laughter] Um I I would just want maybe another designer, let’s say 20 years from now tosay, “Hey, uh if I’m like facing backlash at my school or campus or likelet’s say from this gallery or from my manager for wanting to do Jewish themes in my art, I have examples to to to pullback from that can show me that an alternative path to go.” And I I know we’re nearing the end here, but I Iwould be remiss not to mention my what I think is the most important figure in Jewish art history, some somebody that Ilook back on that gives me that. I mean, besides Betal, which is number one inJewish art history. Um, but I would say Daniel Morris Openenheim,uh, who’s considered to be the first Jewish artist ever, you know, and likeaccepted or at least acknowledged, right? Exactly. And like it’s funny because like I did this writing piecewhere I talked about that and it’s like if you Google the first Jewish artist,Daniel Murenheim came up and I think he was born in like the 1860s or 70s. So obviously he’s not the first Jewishartist. That’s absurd. Um but like you said, he was considered the first because he was the first to be accepted.And what Morates Openenheim did with that is the thing that makes him a legend is that he was the first Jew tobeed in like these salons in Paris and Rome to be trained by non-Jewish masters.And what he did with that he he saw the opportunity in front of him and he did not miss he he he knew what he had todo. what he did at the time this was like fresh post emancipation of Europe’sJews and especially Ashkenazi Jews and from the ghettos and people like at thetime all the conversations happening on the street level was should we emancipate these people are they able toassimilate people viewed the ghetto as some backwards place of religion becausethis is when Europe was secularizing itself with the enlightenment so like what openheim did was he he saw theopportunity and he took He he started making paintings about the ghetto and this was the first Jewishartist accepted and and because of that he got blacklisted from galleries. He got lambasted in the press and he isthat person I think still like a hundred or so years later. We can still lookback at him and unfortunately we’re still in the same position as him. But we need to like remember that Jewishartists did that and and to keep that ball rolling. you you used an amazing word way earlier on in this conversationwhere you’re like talking about Shagal and you’re saying that’s our ancestry. Yeah, we’re both Jewish, but it’s alsolike a lineage. Uh to be a Jewish artist is like a very delicate thing. It’s a very new thing that you know has hadlike a lot of push back even from our own community regarding the second commandment. There’s like a lineage ofJewish artists. It’s like a heritage. It’s a family. It’s a its own very very specific thing that again in terms ofthe most prestigious art institutions like Jewish art is like a very very verynew thing only just about 100 years old. We have this very sacred obligation to to pick up what the bravery of MoritzOpenenheim and what he did for our community and to continue to be brave. Uh that’s that’s my spiel about[laughter] that. Oh that’s amazing. Yeah. Right. I mean u at the time of Napoleon right we’retalking that that emancipation of Jews um yeah it’s it love that love thatright and and you know my my hope is that in we live in a future like you said where we don’t have to referencethese these bad works you know like where we have to uh respond to things or whatever um and uh my one of my favoriteuh Jewish artists in this same legacy that we’re talking about, right? I think you really I love that you called it alineage, you know, a legacy. It really is something that like we should really feel a part of and empowered by. It is afictional artist and it’s it’s Asher Lev from Oh, that book is amazing.Right. I love that book. I I I so often look atthat as like just a blueprint, you know, for for a career and for for uh youknow, being Israel, you know, really being struggling, you know, strugglingwith God. Um and um you know, I also have um uh the contract with God, youknow, the the uh uh what’s his name? The Will Eisner, right? the famousfamous uh um comic book artist who you know you get the Will Eisner award ifyou’re in comics, right? But his Contract with God comic is about um not a shedle but a tenement house inthe Lower East Side in New York City in like the 20s and 30s, right?And uh amazing just like I never read that. I need to get into that. Oh, brother, you’re going to love it.You’re gonna love it. It’s it’s like an immersive world like the rain the way he draws the rainbecause it always rains on this one guy right you know I think that like and II’ve always thought this way comic books comic comics are like high art like Ireally think comic books are like very very sophisticated form of art because you’re like combiningwriting and visual art like it’s a very sophisticated medium you know more waymore than people give credit to and all you have to do is just read the watchmen once and then you can see how likesophisticated the medium is you know Oh absolutely yeah and and that’s wherea lot of Jewish artists existed in the 20th century just like graphic design but in that you know trying to appeal tothe universal you know I think they were chasing that utopian modernist idea ofyou know let’s build our future um regardless of what how it happens you know Um, right.And, uh, yeah, you know, we we got a lot of a lot of great things out of that, you know, especially Jack Kirbyand Ste Stan Lee. I mean, the um, the New Gods. You ever read The New Gods before? No, but I know about it. It It’s been onmy list for so long. I I need to get into that because you know Kabala, you love thisstory, man. Yes. I I need to pick that up. [laughter] It’s a great one, man. Yeah, it’s reallyreally great. Um, and then read it and then we’ll do a show on that one. Okay. Man, I would love that. [laughter]I would love that. Um, so Al, this has been a fantastic conversation. Um, I wanted to know ifthere’s like anything you’re working on right now or something coming up that like we could share and that you’reexcited about. Oh man. Yeah, this this was absolutely lovely and a huge huge honor for me. Um,I would say there there’s uh been a project that I’ve actually been veryquietly working on for the past four years uh that is now coming to fruition.Don’t know how much I can share about it until I have like the physicality in myhands. But um all all I am going to say isDiaspora Diaries coming in 2026. Wow. And I’ll leave it at the end.Okay. Leave it. That’s great. I think that sets the anticipation. Masle masle.Thank you. Thank you. Actually, that’s incredible. Yeah. Congratulations. Thank you. I’m I’m excited. So muchwork. It’s not even done yet. No. Well, you can see the horizon, right? And that’s important. So, itfeels like it’s uh you know that ship’s going to sail. So, fabulous.Hashem, man. Yes. And as well. Um, Alex. Wow. Uh, this was super cool and I’m soglad that we got to do it for the for the for the the podcast and um, man, youyou really are like I I had you on my list as like exemplar uh Jewishfuturist, you know. I think uh I think you do a lot of great stuff about uhbringing our culture from the past to the present, pushing it into the future. Um, you know, I I see you use traditionas a launchpad and not as a museum. Oh, thank you. I love how you use uh um like tun youbuild tun into your actions, right? I mean, and that’s that’s amazing that that sets the kavana, right? Theintention. I mean, you’re just you’re taking this in a completely halah way. So, like that’s no nothing should stopyou, right? You’re the best. Thank you. Like I I always say like no one can can give youa good compliment like another artist can. Like other artists like we since wewe know how to consume each other’s work like we we always like we know exactly what to say to each other. So thank youso much. I’m so uh so humbled and honored. Well my brother, thank you so much andum yeah, we’ll be in touch. We’ll be in touch. This was awesome. Yes. I will see you in the future.I’ll see [laughter] I’ll see you in the future. Have [clears throat] a good one. Shab. Yeah. Shab.Bye. Bye.